Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

For Non-English Speakers, Difficult Language Barriers Become Dire Amid Outbreak

En español, traducido por El Planeta Media

Petrona worked as a housekeeper until the state ordered the closure of all non-essential businesses to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Now the single mother of two young children with only a few dollars in savings and unable to qualify for unemployment because of her legal status, her main source of information is what she sees on her phone.

“The truth is I’m getting my information from Facebook,” she says in Spanish. “I don’t have cable.” Nor does she have internet or a computer. Just a TV with an antenna.

WBUR agreed to use only Petrona's first name in this story because of her concern about child custody issues.

Petrona was born in Guatemala speaking the Quiché language. She has lived in the U.S. for 14 years. She hasn't learned English and Spanish isn't even her first language.

Petrona is one of 1.2 million foreign-born Massachusetts residents and among roughly 500,000 who report to the Census that they speak English "less than very well.”

Whether that means you don’t speak a word, or you understand half of what you hear, about one in every 13 Massachusetts residents struggles to some degree with the language barrier.

It’s difficult enough during normal times not to speak the dominant language. But some observers say that during a deadly outbreak, it could be a matter of life and death.

Petrona says she hasn’t heard Gov. Charlie Baker speak during this pandemic — nor any other public officials talking about the outbreak and what’s being done to lessen the impact.

She says she didn’t know that National Grid — which provides her electricity and gas — announced they would not be shutting off people’s utilities during the outbreak. She didn’t know the housing court is closed for business, meaning she can’t immediately get evicted for not paying rent on April 1.

Advertisement

Petrona is isolated from news of the coronavirus outbreak — and what’s being done to protect people from the disease and its impact. But she is getting some key information.

“I tell my daughters to wash their hands well,” she says, "and that the most essential thing is to ask God for love, and that this sickness doesn’t infect us.”

'People Go Around Like They’re Lost'

Suyapa Perez is a community activist who practices homeopathic medicine in Saugus. She says people who don’t speak English are living in a state of confusion about how society is changing during the outbreak.

"The people go around like they’re lost,” she says in Spanish.

Perez says her English is about 60% proficient, but she’s not lacking for the facts — she went to university in Honduras, and she’s plugged into an array of community groups and follows the latest news online and in local media. It's the broader immigrant community that concerns her, some of whom she says are getting information from unofficial sources.

“There is so much ignorance and so much incredulity,” she says. “People don’t believe in this crisis until it hits them firsthand, because the information people get is from Facebook."

In medical settings, Perez says non-English speakers are at a huge disadvantage — especially when they don’t have language interpreters. One of her neighbors went to a community health center early last week after being sick for four days with symptoms consistent with COVID-19, she says, and there were no interpreters available. She says the woman was communicating with doctors in signs, and they sent her home with some acetaminophen.

The woman’s daughter, Ruth Gabriela Santos, says her 56-year-old mother’s situation got worse every day after returning from the clinic. And with eight people living in the house, they wanted to know if she had contracted the coronavirus. On Thursday, the woman went to the hospital and tested positive, Santos said.

Santos only speaks broken English, and she’s had to communicate with health care workers on her mother’s behalf in English.

“It’s very uncomfortable because these are very delicate matters that you want to deal with in your language,” she says.

Now Santos says her mother is on a respirator at Massachusetts General Hospital. Santos is not allowed to visit, and the nurses say her mother is unable to speak over the phone.

Dr. Joseph Betancourt, chief equity and inclusion officer at Mass. General, says the number of COVID-19 cases coming out of Chelsea represents an "absolute epidemic.”

Betancourt says 35% to 40% of MGH's coronavirus patients are Latino, reflecting a huge uptick from about 9% before the outbreak. That could mean Latinos are disproportionately represented at the hospital by as much as 400% or more — an increase Betancourt attributes to class rather than ethnicity.

Chelsea "fits all the descriptors for a high spread of COVID-19,” Betancourt says. "It is highly dense. It is made up of individuals who are oftentimes cohabitating with multiple family members … who work in jobs where social distancing is not possible."

Despite the onrush of demand for interpreters, Betancourt says MGH is able to provide interpretation for those who need it, with a mix of staff and outside contractors. And he says the hospital is looking for new ways to address the language barrier, like including more Latino doctors in patient rounds.

“Having another clinician there who speaks Spanish will make a huge difference in communications with the family and also getting cultural nuance,” Betancourt said.

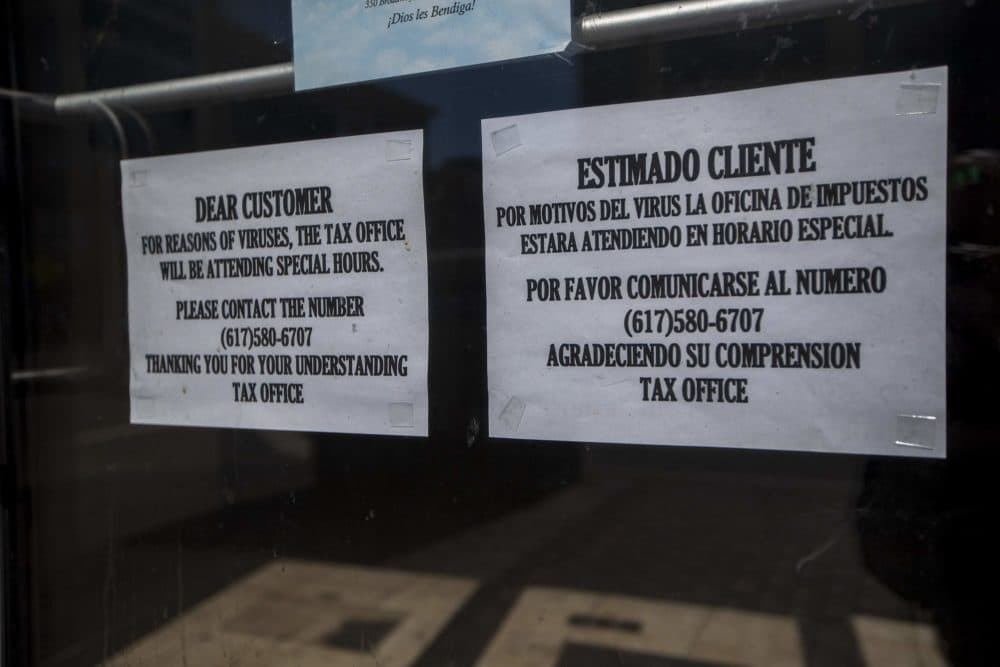

'This Is An Important Notice. Please Have It Translated'

The language barrier doesn’t end in the health care system.

When National Grid announced its customers wouldn’t be getting their utilities shut off as the outbreak goes on, the news went out in English.

A spokesman for the company said that inside customers’ April bills they’ll get a COVID-19 insert that will explain the no-shutoff policy — with a note at the bottom saying: "This is an important notice. Please have it translated.”

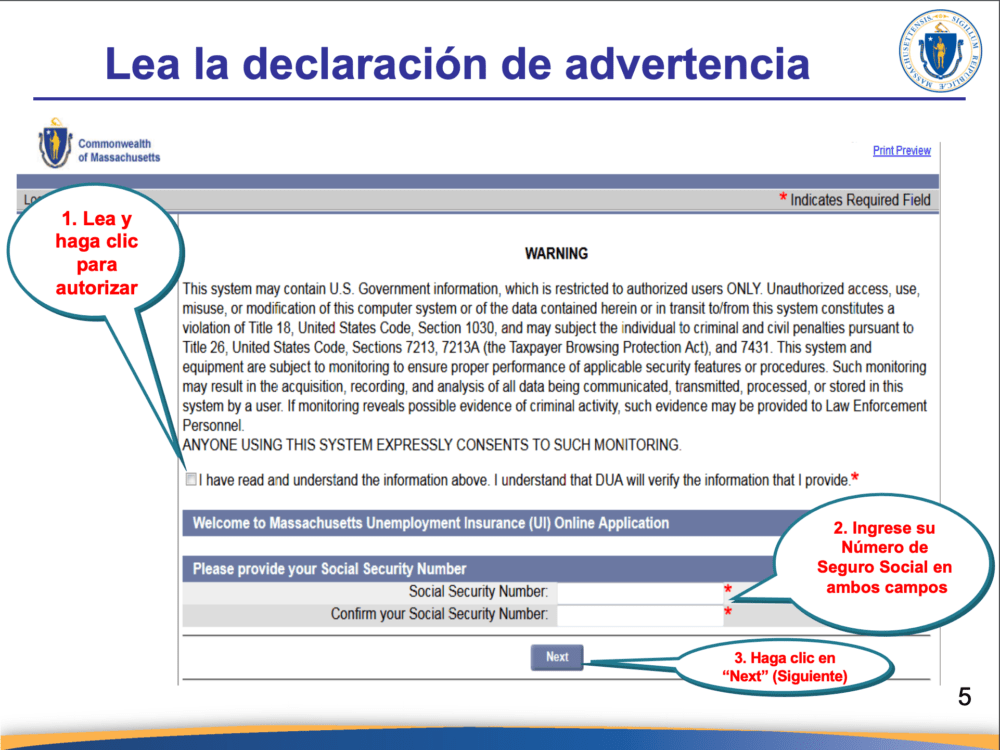

Then, there’s unemployment. If it’s hard navigating that system in English, it’s orders of magnitude more difficult for those who speak primarily other languages.

Over the past few weeks, Department of Unemployment Assistance (DUA) officials have touted a recent cloud migration that they say made the system capable of handling an immense surge in demand. But plans to update the system did not include steps to make it available in other languages.

DUA offers a document that explains in Spanish how to fill out the unemployment online form — but you have to fill out the form in English.

Ivan Espinoza-Madrigal, head of Lawyers for Civil Rights, says the state should be required to have the forms available in Spanish. The lack of access in other widely spoken languages in Massachusetts could open the state to liability over discrimination claims, he says.

"A Spanish speaker, a Haitian Creole speaker … they are experiencing a very painful delay in the processing of their claims,” Espinoza-Madrigal says, "because they are being deprived of the opportunity to go online to complete the same process that English speakers are being allowed to do.”

And Espinoza-Madrigal says the lack of these materials could make the difference of whether families have food on their tables.

A spokesperson for the Department of Unemployment Assistance says in a statement that "DUA is scaling up call center staffing and ... pursuing additional strategies to speed up the application process for non-English speakers."

This segment aired on April 7, 2020.