Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Senior Living Facilities Are Coronavirus Hotspots. Now, Families Wonder If They Should Bring Loved Ones Home

In March, not long after Bill Passman’s parents moved into an assisted living residence in Maryland, his 94-year-old father developed a cough. At first the family didn’t think much of it, even though fears about the coronavirus had recently sent the facility into lockdown.

Bill was more concerned about helping his parents figure out how to use Zoom so the family could still talk."We did get [my parents] to click on the Zoom link, joined it — and the audio wasn’t working," he recalled.

So Bill, who lives in Lexington, bought his parents a new Chromebook. He sent his brother in Maryland to deliver it.

"Literally, as he’s getting to the door to hand it inside so they can wipe it down and take it to their room, an ambulance pulls up," Bill said. "And that was for my dad."

Bill’s father, Richard, was running a fever. That, combined with the chronic cough, sparked concerns about the coronavirus. At the hospital, Richard's condition deteriorated suddenly. He died that night.

Bill’s brother, Hap Passman, was allowed a special exception to visit their mother in quarantine to break the news. He donned a hospital gown, a face covering and gloves. The minute he walked in, he said, it was clear his mother, Minna, had guessed what had happened.

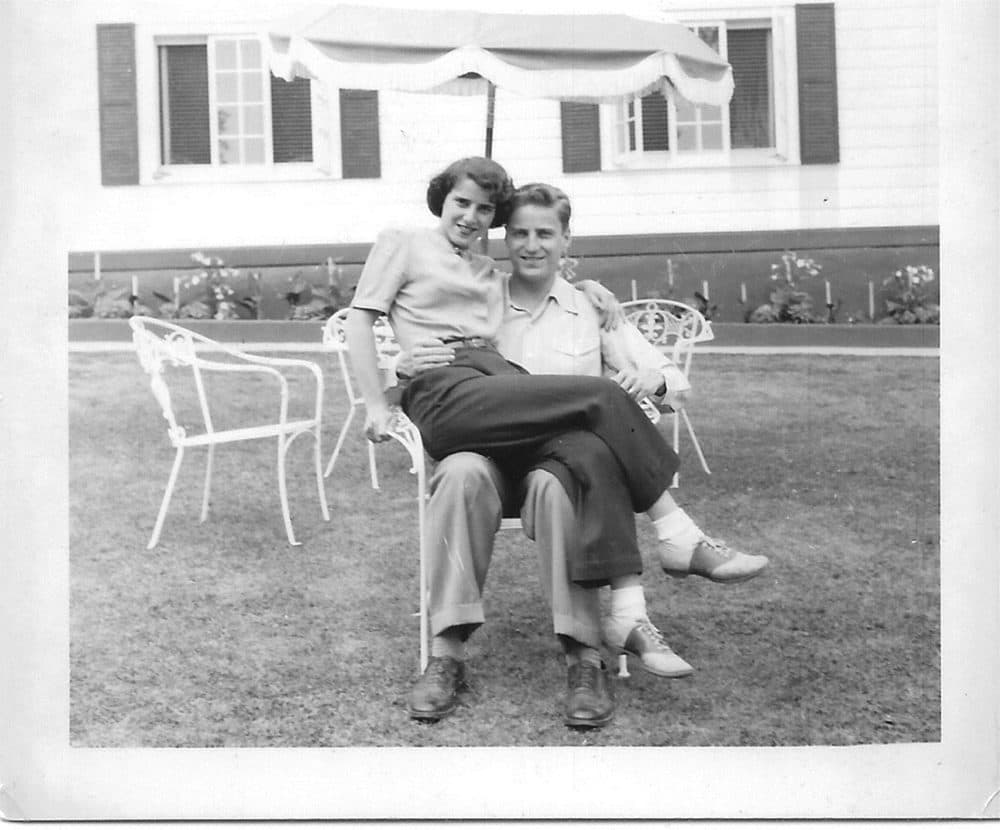

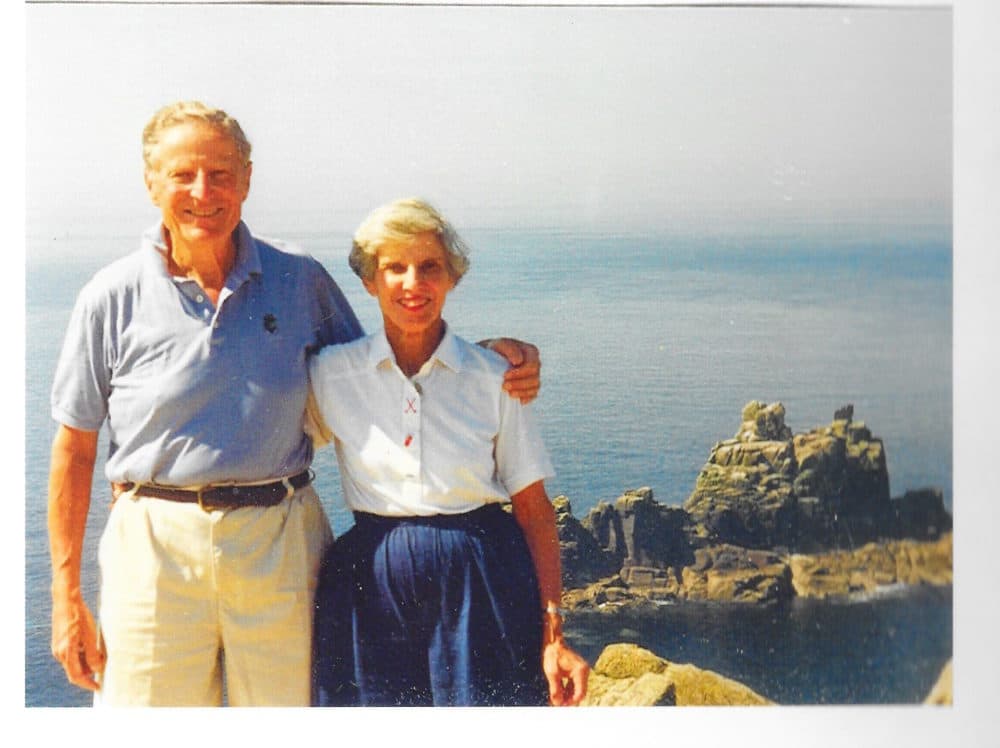

After that, she was confined to her room, grieving the loss of her husband of 70 years alone.

"He didn’t suffer at the end, so I was pleased about that. But I knew I’d miss him," Minna said, her voice cracking.

The family sat shiva for Richard Passman, a retired aeronautical engineer who was once the chief aerodynamicist at Bell Aircraft, over Zoom. Hap struggled with feelings of guilt; he and his siblings had only just moved their parents out of the independent living residence in Florida where they had lived for years.

"I took a lot of this on my shoulders, that it was bad timing," he said. "[That] I, you know, I ruined my parents' life."

A test confirmed that Richard had had the coronavirus. Minna showed no symptoms, but she needed to remain isolated for two weeks, just in case. That’s when Bill really started to worry.

His mother, he said, was "lethargic, dozing, bored and not happy." The family was concerned the isolation was sending her into a deep depression. Hap and his wife wanted to take her in, but Bill agonized over the decision.

"We were concerned about our ability, my brother’s ability, to manage medications," he said. "Whether, if she fell, whether they could pick her up properly."

Advertisement

These are questions a lot of families are asking, as senior living facilities have emerged as hotspots in the coronavirus pandemic. In Massachusetts, more than half of COVID-19 deaths have been at nursing and rest homes. Nearly 150 of the state's 255 assisted living facilities have reported confirmed cases of the virus. These statistics have families very concerned.

"Given the environment in these places and the likelihood of COVID-positive residents or clients, and the challenges of not being able to see their loved one, people are contemplating whether they should be bringing their loved one home," said Kate Granigan, CEO of LifeCare Advocates, a Newton company that advises families about geriatric care.

In response to an uptick in inquiries on state's family resource line, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health released guidelines for families considering taking loved ones out of senior housing. But so far there has been no mass exodus from the state’s senior living facilities.

"If someone's coming home and they now need 24-hour care and assistance and a family member is going to try to provide that, that is in itself a big challenge," Granigan said.

And care-taking help is expensive — for many families, the cost of home health care was the tipping point that led them to senior living facilities in the first place.

According to Granigan, few families are choosing to remove relatives from senior housing, despite fears about the virus and the isolation of quarantine. Most people simply can't take care of loved ones at home.

But the Passmans decided they had to give it a shot.

Two weeks after Richard Passman's death, with Minna still showing no symptoms, they brought her home.

"We counted it down. ... I told her on Monday, 'We're coming Wednesday, you gotta get ready and I'm sending you a list,' " Hap said. "It sounds like a jailbreak."

The family is lucky. The elder Passmans had the foresight years ago to purchase excellent long-term health insurance, and it now pays for a home health aide to visit Minna every few days. Hap and his wife have a bedroom and bathroom on the first floor of their house, so his mother, who uses a walker, doesn't have to use the stairs. The move is not a permanent fix, however. Once the crisis ends, the family plans to move Minna back into assisted living, where she can be part of a community.

But right now, she’s pretty happy to be home.

"The day she moved in, it seemed like she got 15 years younger. It was such a dramatic shift," Bill said. "I think all of us cried."

This article was originally published on April 29, 2020.

This segment aired on April 29, 2020.