Advertisement

Quarantine Double Feature

Quarantine Double Feature: Men On The Margins

Quarantine Double Feature is a series in which we pick two films available for streaming and discussion while we wait out this crisis at home. This week: Men on the Margins.

It probably sounds strange these days now that everybody’s got a seemingly infinite supply of entertainment available at a click, but for a long time, there were some movies that you just couldn’t find anywhere. When the home video boom hit, music rights became a big bone of contention, as popular songs that had been cleared for theatrical and broadcast showings now needed to be renegotiated for a new medium. This made some films prohibitively expensive to release on videocassette, while others bounced around in legal limbo, going in and out of print for assorted, arcane reasons.

Two of my favorite movies by two of our finest filmmakers, Robert Altman’s 1974 “California Split” and Peter Bogdanovich’s 1979 “Saint Jack” have long dwelled in the back alleys of their respective directors’ filmographies, movies more written about than seen, boasting an ardent band of acolytes. In a way, this seems somehow appropriate, as they’re modestly scaled pictures about men living on the margins, hustlers scraping by from score to score. Less grandly ambitious than canonical works like “Nashville” or “The Last Picture Show,” they feel more personal and idiosyncratic. For a long time, these films were almost impossible to find — I had a treasured VHS of “California Split” that I’d taped off of Bravo at 2 a.m. back before it became the “Housewives” channel — so imagine my surprise to discover they’re both now streaming on Amazon Prime.

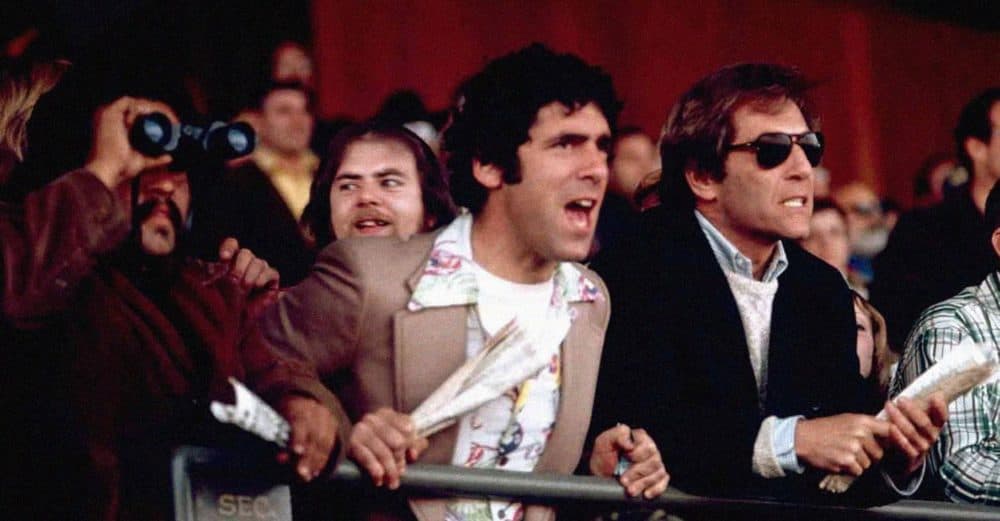

Written by child actor, gambling addict and picaresque Hollywood character Joseph Walsh, “California Split” spins the semi-autobiographical story of a mild-mannered magazine writer (George Segal) who strikes up a simpatico friendship over the poker table with Elliott Gould’s fast-talking hustler. Recently divorced and rudderless, Segal’s smiling milquetoast slides easily into his new pal’s chaotic lifestyle, ditching work for days at the track and enjoying a cold beer with his Froot Loops in the morning. Possibly the most Altman-iest of Robert Altman movies, it’s all buzzy, overlapping patter and jazzy insouciance. The first film shot with the director's patented 8-track sound recording system, it's a hive of voices humming in low-rent, mildewy card parlors and racetrack grandstands. This all feels so extemporaneous and unrehearsed it takes a couple of viewings to realize how carefully plotted out it is.

Walsh’s screenplay was a hot one around town. Initially, Steven Spielberg was set to direct with Steve McQueen starring, but when Altman and Gould came aboard they brought their brand of disruptive, hepcat swagger that the two perfected in their previous collaborations “M*A*S*H” and “The Long Goodbye.” There are few things I find funnier than the chain-smoking motormouth persona Gould established in his Altman pictures, at once dorky and dashing, here wearing a blazer over his Hawaiian shirt. He’s got a perfect scene partner in Segal, the two scat-singing and riffing on top of one another like bebop musicians. The way they crack each other up is contagious, with some of the most genuine laughter I’ve ever seen captured on film. (I’m not sure it’s even possible to act Segal’s reaction to Gould’s priceless “one-armed piccolo player” routine. It just explodes out of him.)

But we can also see that these guys are constantly kicking up chaos to stave off something, an emptiness that’s slowly eating away at the core of the movie. They’ll bet on anything — horses, basketball, who can name all seven dwarves — looking for what Gould calls “the action,” looking for kicks that the straight world doesn’t offer because they don’t have anything else. But the bigger the odds, the smaller the payoff. By the time these characters find themselves on a record-setting winning streak in Reno, they’re two dogs who caught the car, confronted with the meaninglessness of the chase.

It wasn’t written that way initially. The final scenes were improvised by Altman and the actors, much to the studio’s discontent. It’s not a commercial ending but it’s the right one for this movie, giving ballast to the benders and all the banter, making “California Split” something sadder and more philosophical than just a romp. In an interview with critic Kim Morgan, Walsh claimed that after seeing the final film Spielberg said to him, “You know. I would have definitely made more money with this film. But I could never have made a better picture.”

Advertisement

One-time Hollywood wunderkind Peter Bogdanovich was coming off of three massive flops when he made “Saint Jack.” The blockbuster days of “What’s Up, Doc?” and “Paper Moon” seemed long behind him, with the popular sentiment one of schadenfreude as tabloids cheerfully knocked the admittedly arrogant director and his too-beautiful girlfriend Cybill Shepherd down a few notches. (Bogdanovich’s story is the subject of a new Turner Classic Movies podcast and is indeed stranger than fiction. For example: during this time, a broke Orson Welles was crashing in his and Shepherd’s guest room.)

The new film found him back where he began, working for exploitation movie maestro Roger Corman, who’d bankrolled Bogdanovich’s first film “Targets” a decade earlier. Based on a novel by Paul Theroux, “Saint Jack” almost didn’t get made at all. Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Productions owned the rights to the book, which were eventually relinquished in a settlement after the magazine published unauthorized nude stills of Shepherd from “The Last Picture Show.” (Hef retained an executive producer credit on the final film.)

“Saint Jack” stars Ben Gazzara as a genial ex-pat pimp living on the fringes in Singapore. Much like “California Split,” it’s a prime example of what people are talking about when they call something “a ‘70s movie” — which basically means a rambling character study with an unconventional leading man and an undertow of melancholy. But Singapore authorities were not exactly fans of Theroux’s novel and would never support production of a movie that made their country look so seedy, so Bogdanovich submitted to them a phony screenplay for a romantic comedy and secretly shot “Saint Jack” instead.

Gazzara’s Jack Flowers could be a cousin to his doomed strip club entrepreneur in John Cassavetes’ “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie.” (This can hardly be an accident, as Bogdanovich pitched the actor on the project while shooting a cameo in Cassavetes’ “Opening Night.”) His regal bearing again offsets the seaminess of his surroundings. Jack carries himself as a man out of time, unflappable in the face of danger and smiling politely at death threats from rival gangsters. He breezes through the movie with a generous, nonjudgmental attitude. When Jack asks a sex toy salesman how his kids are doing, you get the sense that he genuinely wants to know.

The film follows Jack’s ups and downs over the years, pegged to annual visits from a Hong Kong-based accountant played by Denholm Elliott. There’s a touching tenderness to their friendship, which feels far from the drunken macho bluster from other Englishmen, soldiers and sex tourists we see hanging around these bars. America eventually intrudes in the form of a smooth, sociopathic CIA operative played by the director himself, pushing at the boundaries of things Jack will do to earn a buck.

Bogdanovich isn’t much interested in paying attention to the plot, instead conjuring a hazy, hangout vibe in this humid, vanishing world. Photographed by the legendary Robby Müller, it’s a movie about textures and low-key interactions, as we watch a quaint, regional way of life slowly overtaken by sleek skyscrapers and shady bureaucratic operations. In a clever bit of casting, one-time James Bond George Lazenby shows up as an American senator, but it’s in Gazzara’s sad eyes and rueful smiles that we find our real international man of mystery.

“California Split” and “Saint Jack” are both streaming on Amazon Prime and available to rent from most video on demand outlets.