Advertisement

Mass. Must Implement Ongoing Coronavirus Testing At Nursing Homes, Advocates And Experts Say

On April 27, Gov. Charlie Baker and Health and Human Services Secretary Marylou Sudders announced a new package of aid for nursing homes struggling to contain the coronavirus. They said the state would make $130 million available for facilities that did two things: passed a health and safety audit, and tested at least 90% of all residents and staff.

The auditing process is ongoing — nursing homes will be monitored through June — and the testing deadline is Monday, May 25. But given the supply and personnel shortages that have hindered testing efforts nationwide, it’s unclear how many of the state’s 383 nursing homes will complete this “baseline” testing on time.

And beyond this baseline testing, senior care advocates generally agree that the best way to contain the spread of the virus long-term will be a targeted and ongoing “surveillance” testing program. This means long-term care facilities should test residents and workers not once, but often.

“Baseline testing allows us to take a snapshot in time of the virus in our facilities,” says Tara Gregorio, president of the Massachusetts Senior Care Association. “However, baseline testing in and of itself is not enough. What we need is regular surveillance testing so that we can monitor [residents who] test negative and ensure that they continue to test negative.”

Dr. Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, put it more bluntly during a recent call with reporters.

"Baseline testing for the virus alone is not an appropriate goal. And in particular, [tying] COVID response funds to this, I think, is not appropriate. And the reason for that is doing one cross-sectional sample — one sample time point of the nursing home — gives you very little information if you’re only testing for a virus," he says.

One potential solution would be to retest everyone in a facility every week or every month, but experts say that’s a poor use of limited resources. There are about 38,000 older adults living in nursing homes in the state — plus thousands of employees — and securing that many tests on a regular basis is not realistic.

Advertisement

“The supplies for testing are still extraordinarily limited and very, very difficult to come by,” Mina says. “We can’t get the supplies we need here [and] we’re Harvard and M.I.T. and Boston — we’re the biotech hub of the world in some ways — and we can’t get these supplies.”

What’s more, regular baseline testing would be logistically challenging. The National Guard, which has been testing nursing home residents since early April, already can’t keep up with demand, and the state had to discontinue a program that asked nursing home staff to test residents after many tests came back contaminated.

So what would a surveillance testing plan look like? The MIT-based COVID-19 Policy Alliance is working with Mina and Gregorio to figure that out.

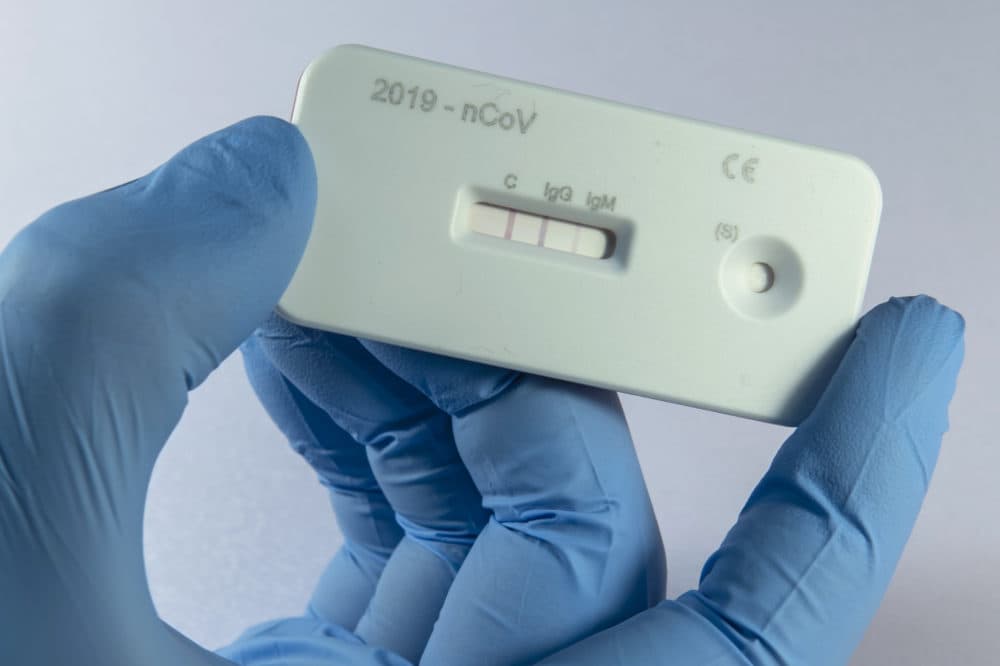

The Policy Alliance team has partnered with Pro EMS and the Broad Institute to test between 1,000-1,400 people every week at six Boston nursing homes as part of an eight-week surveillance testing pilot program. In addition to weekly diagnostic or “PCR” tests, which tell you who has the virus at that point in time, the team will also be conducting blood antibody or "serology" tests on all participants, which can indicate if they've been exposed to the virus.

“The state is really focused on this baseline testing — this one-time PCR test. From our perspective, the way you make that baseline testing valuable is you add serology to it, and then you build it out into a broader surveillance testing framework,” says Tess Cameron, of the COVID-19 Policy Alliance Group. “There are a lot of ways to think about how to do repeat testing in a way that’s also being thoughtful of resources this consumes."

The framework for a state-wide surveillance testing program is still far from complete, but the Policy Alliance's pilot will help determine how to deploy limited resources in the most cost-effective and medically useful way.

“I went into a nursing home [recently that] was 13% positive across the residents and staff,” Mina, the Harvard epidemiologist, said during the recent press call. But just knowing that 13% of residents and staff have the virus can’t tell you “if they’re on an upswing to have a massive outbreak or if they’re finishing up with an outbreak.”

However, since his team has been doing surveillance testing at this facility, they know that a month ago, the positive rate was closer to 30%. “So we know then that this 13% means that they’re on the downslope,” he says.

In other words, this nursing home probably doesn’t need the same resources as a facility where the virus has just started sweeping through. The same would go for a nursing home where serological testing shows a certain percentage of the patients have already been exposed.

But surveillance testing is easier said than done, and requires logistical and financial support from the state, says Cameron of the Policy Alliance.

“COVID-19, especially in these nursing facilities, is not going away next month. This is going to be something that we’re dealing with for some time," she says. "And if we think that surveillance testing is the way to go, there are some pretty fundamental things that are going to have to be put in place in order to enable that."

Funding, for example.

Most nursing home residents have Medicare or Medicaid, so the cost of their diagnostic tests should be covered. But for those who don’t — and for staff, who mostly have private insurance — Cameron says it’s not clear how reimbursement would work. For the baseline testing program, the state has said it will refund nursing homes up to $200 per test. But for their pilot surveillance program, they’ve had to rely on outside foundation money.

“The billing codes, the supply chain for test kits and the test processing capacity — these are all big challenges that are going to require a lot of organization," she says. "And that organization is going to require support from the state."

Asked whether Massachusetts HHS was looking into surveillance testing, a spokeswoman referred WBUR to a statement about the baseline testing program.

Tara Gregoria of the Massachusetts Senior Care Association, meanwhile, says nursing homes are clamoring for surveillance testing, and she hopes the state is listening: “I believe that the Commonwealth will find its way to a surveillance testing program because we have the shared goal of protecting the residents and staff from this virus.”

She says she’s encouraged by the Policy Alliance’s pilot program, and thinks “it’s likely to serve as a model for the commonwealth and also, hopefully for [nursing homes across] the nation, too.”

This article was originally published on May 22, 2020.