Advertisement

In Trove Of Emails To State Officials, Feds Downplayed Coronavirus Risks

A steady drumbeat of emails and updates about the coronavirus from federal health agencies to state officials repeatedly downplayed the looming threat in the first three months of 2020, causing confusion and delaying action in Massachusetts and across the country.

More than 115 emails sent between January and mid-March, and reviewed by WBUR, reveal how the federal government portrayed the virus to those making decisions in Massachusetts.

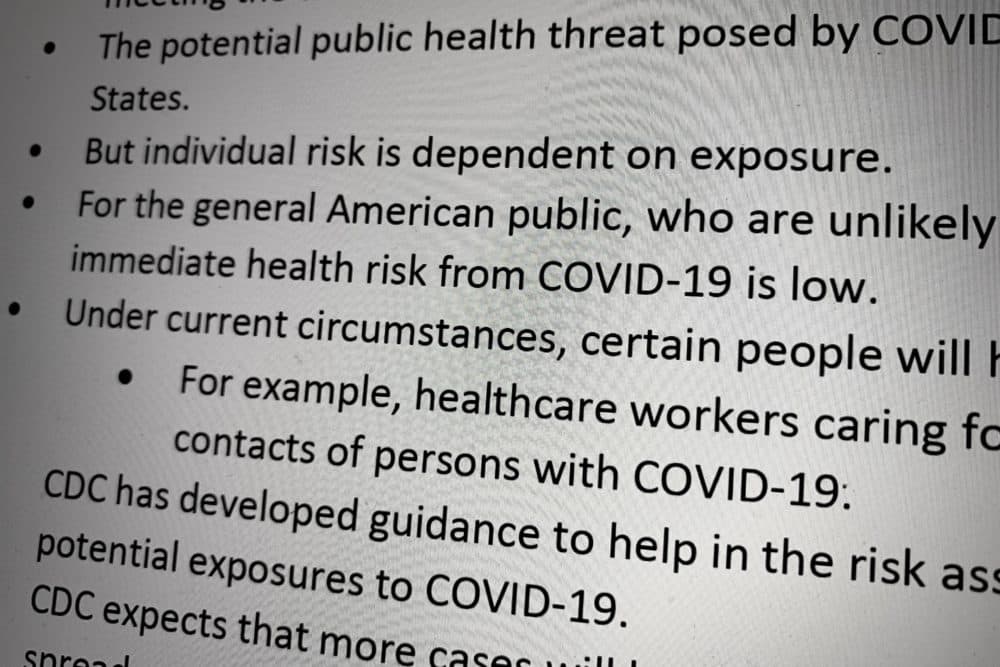

Well into March, federal officials stated in emails that “the immediate health risk from COVID-19 is low” for most Americans, even as the outbreak was exploding overseas and the death toll was slowly rising at home.

As the numbers soared, President Trump and his staff compounded the problem with conflicting tweets and comments. The public and even experienced doctors were in the dark about the gravity of the situation.

“It was not clear to me how rapidly it was spreading,” said Dr. Brita Lundberg, an infectious disease specialist in Brookline who’s part of the Massachusetts COVID-19 Action Coalition, a group of doctors advocating for medical staff and patients during the pandemic.

Lundberg reviewed some of the emails obtained by WBUR. She learned for the first time that by Jan. 27, there were five infections in four different states — “a tremendous risk,” she said, already on a dangerous path to a wide spread.

The Baker administration declined to comment on whether it had received sufficient information from federal officials about the seriousness of the virus. In a statement, Department of Public Health spokeswoman Ann Scales said the governor's office and top state health officials had been "in frequent contact" with U.S. officials.

"The Administration has regularly received updates on guidance, advisories and recommendations from federal public health officials, and will continue to take steps to support the health and safety of the residents of Massachusetts," she said.

Early on, the focus was singularly on China. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Jan. 31 announced a public health emergency, and President Trump issued an order to block non-U.S. citizens traveling from China. The first coronavirus case in Massachusetts would hit the next day.

Federal and state talking points on Feb. 7 were that the virus was risky but posed little threat to Americans. That same day, Kevin Cranston, director of the Massachusetts DPH’s Bureau of Infectious Disease, told the federal government the state would need help securing supplies if things got bad.

“Attached please find the brief list we discussed on our call of the major needs we have identified to date,” Cranston wrote in an email to the regional head of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Among those, he said, “Possible need for access to national stockpile for N95 masks, gloves, gowns, face shields.”

Few predicted just how desperate that need would become, only a handful of weeks later. The national stockpile itself would run short of supplies.

Advertisement

As February ticked by, the near-daily emails kept coming to the state from Washington, highlighting federal update calls and CDC media telebriefings. On Feb. 13, the CDC communiqué to Massachusetts and other states said the nationwide case count was 15. And it made this seemingly reassuring claim: “It’s important to note that this virus is not spreading in the community in the United States at this time.”

Scientists would later discover the virus had in fact been spreading within communities long before CDC officials realized it.

Messages and comments coming from federal officials were still focused on stopping the spread from China. “The greater risk is for people who have recently traveled to China or their close contacts,” one CDC email said. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, then running for president, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, concerned about a backlash against Asians in the United States, encouraged people in tweets to eat and shop in Chinese neighborhoods.

Then, on Feb. 24, the CDC informed states in an email that the coronavirus was spreading not only in Asia, but also in Italy.

The next day, a glimmer of stark reality slashed through the fog. At a press conference, Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, gave a serious warning, angering the president.

“It’s not so much a question of if this will happen anymore,” she said. “But rather more a question of exactly when this will happen and how many people in this country will become infected, and how many of those will develop severe or more complicated disease.”

The same day, members of the Trump administration confused that message, saying the virus was “contained” in this country. Trump, in a tweet, said, “The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA.”

Near the end of February, the numbers of infected people abroad were head-spinning: 80,969 cases in 38 countries, and 2,715 deaths in China, according to the World Health Organization. Yet somehow U.S. officials seemed to be clinging to the notion Americans would avoid the impending crisis.

An email to state officials on Feb. 27 from the Food and Drug Administration carried a heading in bold, “No outbreak-related shortages identified, FDA continuing to closely monitor supply chain.”

In that email, the FDA said it was “keenly aware” an outbreak would impact the ability to acquire N95 masks and other critical supplies for front line workers. But it saw no immediate evidence to cause concern. “Please be assured, if a potential shortage or disruption of medical products is identified by the FDA, we will use all available tools to react swiftly to mitigate the impact on the U.S.”

Barely two weeks after that missive, hospitals and state agencies were scrambling to get their hands on enough N95 masks, gowns and other gear.

By March 3, the CDC started listing the number of cases and deaths at the top of its email summaries. There were 60 cases in 12 states, and six deaths in Washington. (By the end of that day, the number of deaths rose to nine.) The CDC was now acknowledging community spread but said in an email that people in those areas faced an “elevated though still relatively low risk of exposure.”

Then the virus really started to take off.

“In seven days, the number of cases increased by a factor of 10."

Dr. Brita Lundberg

Friday, March 6, was a watershed day in a number of ways — and the start of a grim seven-day stretch. The CDC in an email said there were now 164 cases in 19 states, representing all parts of the country, and 11 deaths. News also broke that eight people were believed to be infected with the virus after a Biogen Inc. conference in Boston in late February; as many as 175 people had been exposed.

“So it's widespread,” Lundberg said, reacting to the CDC emails obtained by WBUR, detailing a rate of spread she said was not fully grasped at the time. “The horse is out of the barn, as we like to say in medicine. Houston, we have a problem on our hands and you need to act with great speed.”

Yet few in state or federal government let on that they were worried.

Baker flew to Utah for a family ski vacation on the 6th (he would return earlier than planned, three days later.) On March 9, Trump tweeted: “Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of CoronaVirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that!”

The stock market had its worst day since 2008.

Another precious week would pass, and more people would become sick, before the federal or state government would take more serious measures.

On March 10, the state announced 92 cases of coronavirus — more than double the prior day’s count. Most of them had attended the Biogen conference. Baker declared a state of emergency.

The next day, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a global pandemic, affecting 118,000 people in 111 countries. It had already killed 4,291.

And the numbers were now soaring in the United States, too. The CDC, in a March 12 email to the state, said there were 1,215 cases of COVID-19 in 42 states. Thirty-six people had died.

Still, the CDC said, “The immediate risk of being exposed to this virus is still low for most Americans, but as the outbreak expands, that risk will increase.”

Lundberg, the Brookline doctor, said even health care providers who were closely tracking the situation were not getting the full picture — nor was the state ringing alarm bells.

“In seven days, the number of cases increased by a factor of 10,” she said. “I did not realize, as an infectious disease physician, that COVID was growing exponentially in our country in early March.”

The president would declare a national emergency on March 13.

On Sunday, March 15, Baker said he had no plans to shut down the state, and called rumors to that effect "wild speculation."

That night, in a 9:05 p.m. email marked urgent, the federal government told the states it was recommending that all events with more than 50 people be canceled or postponed for eight weeks. Baker took it a step further the following day, banning gatherings of more than 25 people and closing schools and restaurants for dining out.

Lundberg said it’s easy to criticize the government with the advantage of hindsight. Still, she said, “They could've and should've locked it down at least at the beginning of March, at least when it started increasing exponentially.”

It wasn’t until eight days later, on March 23, that Baker ordered all non-essential businesses in the state to close — stunning residents who had no idea the stay-at-home advisory would end up lasting over two months. The state reported 777 confirmed cases of the virus.

Meanwhile, masks — today considered a critical part of keeping people safe, along with social distancing — weren’t recommended by the CDC for the general public until April 3. The president said he probably wouldn’t wear one.

A full week later, on April 10, Baker recommended masks, as Massachusetts became one of the top five hardest-hit states in the country. He would not make masks mandatory in public until May 6.

So far this year, more than 103,000 people in the commonwealth have been infected with the coronavirus, according to the Department of Public Health. Nearly 8,000 are confirmed to have died.

WBUR's Jesse Costa contributed graphics and design to the timeline in this report.

This segment aired on July 1, 2020.