Advertisement

‘Social Movements Are Contagious’: Protests Within Mass. Companies Are Part Of A Growing Trend

En español traducido por El Planeta Media.

If you happened to be shopping at the Whole Foods on River Street in Cambridge last month, you may have gotten the vibe that something was up.

Small groups of employees were huddled together, whispering. One by one, they took off their plain face coverings and replaced them with masks that said "Black Lives Matter" in bold white letters across the front. Then, one by one, they were called into the manager's office and told, in essence, that the masks violate the company's dress code. The employees would have to take them off or go home.

So, what did they do?

They walked out.

In front of the store, the 25 masked employees were greeted by a small crowd of cheering supporters and a few local journalists. This was no mere workplace disagreement — this was a full-on, organized protest, aimed at pressuring Whole Foods to let workers wear clothing supporting the Black Lives Matter movement.

"That's such a basic statement, and for that to be considered controversial or political, just really doesn’t sit right with me," said Suverino Frith, who works as a cashier at the store. After being sent home five times for continuing to wear the mask, Frith, who is 21, said he knows he’s risking his job by walking out.

"The idea of facing a huge corporation, it’s a scary thing. It’s not something you take lightly,” he said.

Despite the obvious financial risks, employee-led protests like this have been playing out within companies in Massachusetts and around the country. Inspired by demonstrations in the current movement against systemic racism and debates in the halls of government, these workers are publicly calling out their own bosses.

Advertisement

According to experts who study labor-management relations, it's the latest in what has been a growing trend of "employee activism," and it is now playing out in industries as varied as retail, food service, media — and even within nonprofits, and state and federal governments.

"We see this dramatic shift in the cultural zeitgeist," said Ethan Rouen, who studies labor at Harvard Business School. "And so it's all of a sudden easier for these employees to get their customers on their side. They already know their customers care about these issues."

Workers are feeling emboldened after seeing protests over racial injustice get mainstream attention, Rouen said. That goes for employees at huge corporations (such as Starbucks and Costco), as well as smaller companies such as the Boston-based chain Tatte Bakery & Café.

Last month, a small group of current and former Tatte employees demanded the company do more to support the Black Lives Matter movement and address allegations of bias within the company. To put pressure on Tatte's leadership, the group used tactics including petitions, open letters and a picket line.

The company responded by agreeing to make changes, and the CEO announced she would step aside from day-to-day management of the business she founded.

"The interesting thing is this is not new," Rouen said.

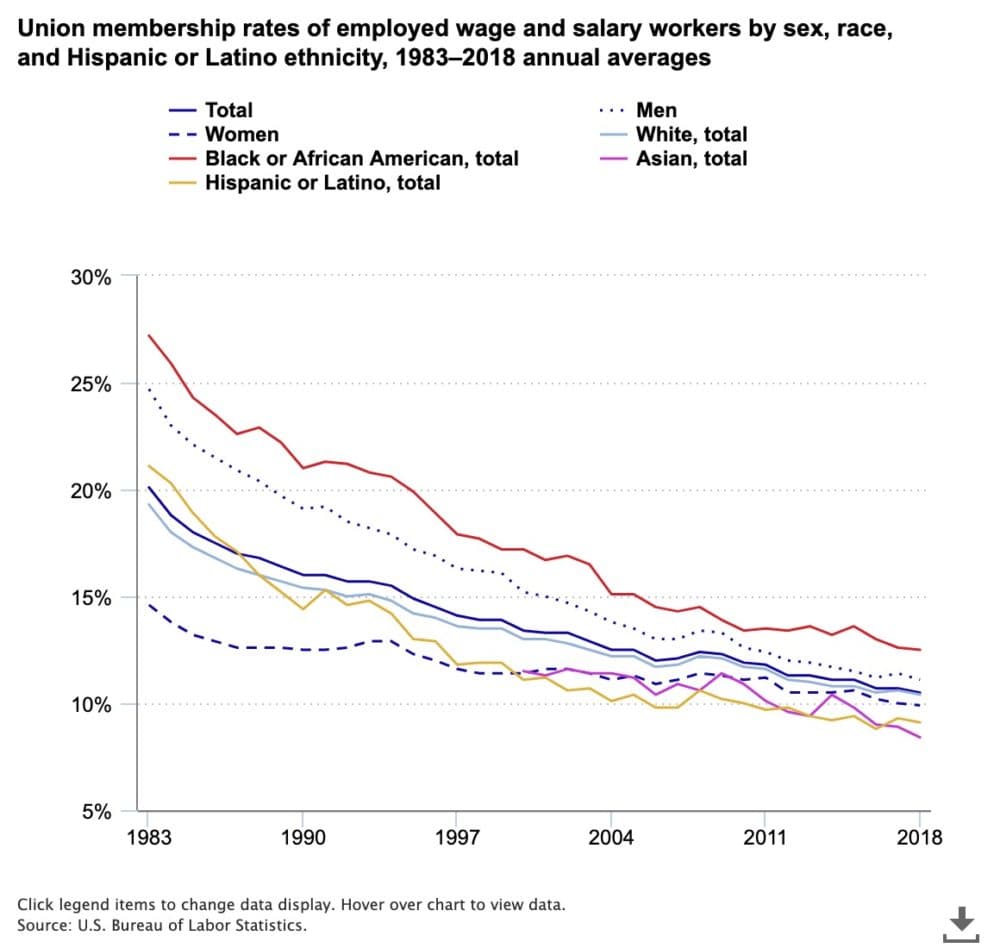

Using a framework that first became popular in the 1970s, Rouen explained that workers who are unhappy with their employer generally have three options: voice their concerns, stay quiet, or exit the company. In the past, many employees would voice complaints through a union. But over the last few decades, union membership has shrunk. Today only about 10% of U.S. workers belong to a union, down from about 20% of workers in 1983.

"What’s replaced this formal organizing power is organizing through social media," Rouen said.

On top of that, non-union workers have been increasingly willing to resort to protests in recent years, said Mae McDonnell, who studies the intersection of corporations and social movements at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton business school.

"There is very clear evidence of a strong growth in employee activism in that data," McDonnell said. Her research focused solely on tech firms, but she found a striking trend: "In the first half of 2015, there were six instances of employee activism in tech firms reported in mainstream media. In the first half of 2020, there were 60."

One reason for the increase, McDonnell said, is that companies have embraced causes like environmental responsibility and racial justice as part of their marketing, attracting a generation of young millennial workers who are passionate about the same issues.

Research on younger workers shows they care a lot about whether a company’s values align with their own.

"They’re more willing to select those firms," McDonnell said. “They’ll work for those firms for less money than they would otherwise, they’re more likely to stay for those firms, and they’re better workers, they’re less likely to call in sick.”

The deeper companies wade into moral and social issues, however, the trickier it can be to manage, especially if employees believe the company is acting in a manner that runs counter to those values.

Last summer, after Wayfair employees in Boston learned the company had done business with a contractor who provided furniture to a federal detention center for child migrants, hundreds of workers signed an open letter opposing the deal, then staged a walked out.

The employee action at Whole Foods in Cambridge is another example.

"We’re easy to replace — 100%. I know for a fact, we can get fired one day and then there’s someone new," said Cedrick Juarez, one of the protesters who walked off the job at Whole Foods because he couldn’t wear a Black Lives Matter mask. "This is the best job I’ve ever had. But if they can’t support my brothers and sisters, then how can I work in a place that doesn’t support it?"

Rather than quit, Juarez, 27, said he’ll stick around so he can keep protesting the company policy.

And if that fails, there’s always that other American tradition — take 'em to court. In fact, a couple weeks after that walk out, several of the workers sued Whole Foods.

Labor experts say employee activism of this sort has been on the rise for years, and may eventually shift the power balance between labor and management.

"I think this illustrates that there's an enormous amount of pent-up frustration in the workplace," said Thomas Kochan, a professor at MIT's Sloan School of Management.

Research shows that employees want a voice not only on issues such as wages and working conditions, he said, "they also want a voice in influencing what their organization stands for."

Kochan added that he believes the protests playing out inside companies today may become more common, eventually leading workers to demand fundamental changes in public policy. With that in mind, he said business leaders may want to come up with new ways to address workers’ concerns before they spiral into protests.

After all, Kochan said, "All social movements are contagious."

This article was originally published on August 04, 2020.