Advertisement

Report: Entrepreneurs Of Color Faced A Huge Funding Gap Before COVID. It May Be Worse Now

Resume

Entrepreneurs of color are less likely to get the funds they need to grow their businesses than white entrepreneurs in Massachusetts. And this capital gap has likely gotten worse during the pandemic, according to a new report out Thursday from the Boston Indicators.

The report found entrepreneurs of color in the state already had an unmet financial need of roughly half a billion dollars a year. And even some of the most successful entrepreneurs of color have faced persistent funding challenges.

Inside a small office in Copley Place sits one of the largest businesses in the state owned by a person of color: DRB Facility Services. (That DRB used to stand for "Done Right Business.")

Anthony Samuels is the founder and CEO of the janitorial, landscaping and snow removal company, and has run it for 27 years. DRB Facility Services provides janitorial services at Copley Place, as well as Blue Cross Blue Shield, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Tufts University and Northeastern University.

These are big lucrative contracts for sure. The company brings in $20 million a year in revenue, Samuels said. But he wasn't always in this position. It's been a slow climb, he said.

"I mean, 27 years is kind of a long time," Samuels said. "So, if you look at it, I'm at $20 million — 27 years. I know companies that don't look like me that had tons of money and they are doing hundreds of millions of dollars right now and they have not even been in business for over seven, eight years."

Samuels said early on, it was a struggle to get the money he needed to grow his business. He even went through a few banks over the years, including FleetBoston Financial (which later merged with Bank of America), Sovereign Bank, Citizen's Bank and Eastern Bank.

He got some small bank loans, but it wasn't quite enough to take him to the next level. He said he has even had to drop bids on some jobs.

"I could have taken on larger contracts if I had more capital," Samuels said.

This lack of capital — or unmet need — hits entrepreneurs of color hard. They're less likely than white entrepreneurs to get financing — even when controlling for risk, according to the Boston Indicators report.

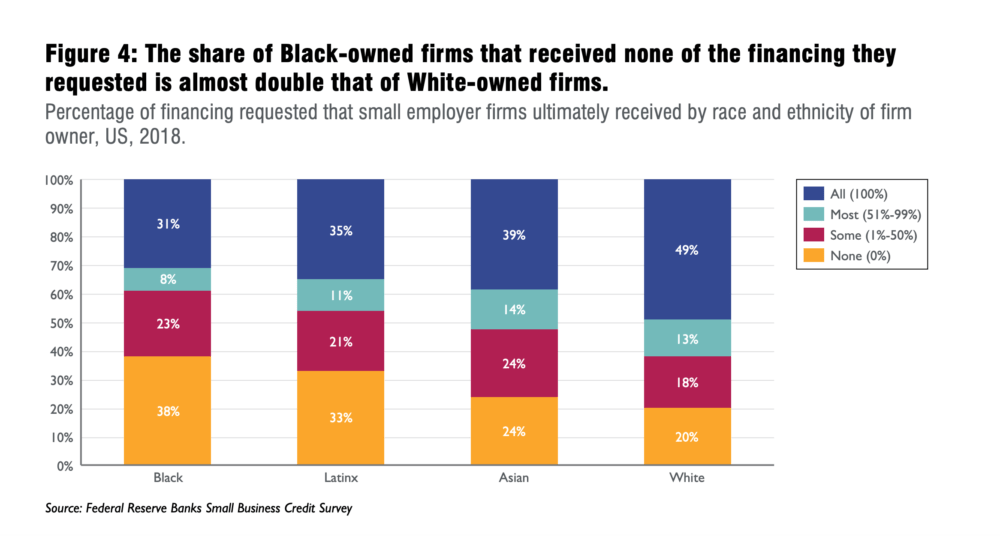

The report pulled data from the census, the Federal Reserve and several business surveys. It found just over half of all entrepreneurs don't get all the financing they apply for. But among entrepreneurs of color, it's more like three-quarters. According to the report, that translates to $574 million a year.

Boston Indicators research manager Trevor Mattos said this results in low business ownership among Black and Latino communities, even though they start as many companies per capita as other groups.

"It's not a lack of innovation, it's not a lack of folks having a great idea and wanting to run with it," Mattos said. "It's a matter of who's able to survive in the market and have access to the necessary resources to make their businesses work."

Samuels said he didn't have many resources early on. He didn't have a lot of equity in his home or collateral to leverage. The report notes systemic barriers have prevented people of color from building wealth through home ownership — the primary way most families build and pass on wealth.

This racial wealth gap is a key reason for the disparities in getting capital. Another key reason is racial discrimination. It's something Samuels said he's felt at times.

"It's one of those things that, you know, it's there," Samuels said. "No one's going to tell you that I chose this other company because I was more comfortable with them than going with you."

The Boston Indicators report also found entrepreneurs of color receive less favorable treatment from loan officers — who are often less helpful, and ask them more invasive questions.

Samuels eventually found a banker who gave him a million-dollar line of credit. That was a big turning point — and helped him grow. He also got financing from other sources like the Business Equity Fund, which allowed him to land much bigger contracts. He also got help and guidance from mentors along the way.

"In Boston, it's not as easy for a minority-owned company to be successful," Samuels said. "When you look at the statistics, you could see that there are not many companies that look like mine that are doing well."

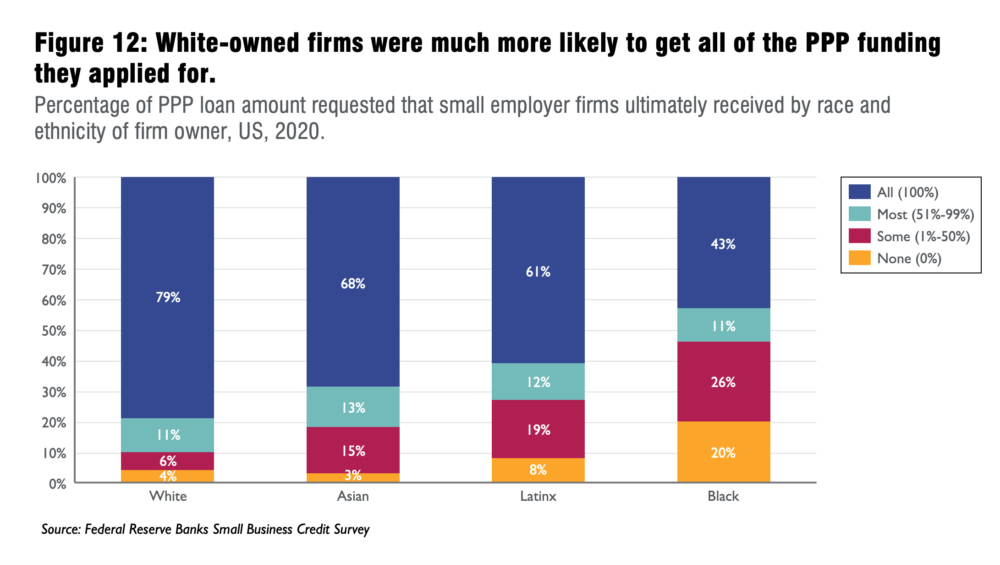

And the capital gap has likely been made worse by the pandemic. The Boston Indicators report highlights polls that found, nationally and in Massachusetts, businesses owned by people of color were less likely to receive the PPP funds they applied for.

"The need well before the pandemic struck was just so, so high," Mattos said. "And I think it'll take more than just trying to, say, stop the bleeding in the context of the crisis. It's going to take a really significant investment to close these gaps in access to capital."

The report recommends several possible solutions to do just that. Here are just some of the recommendations:

- Create a $100 million state fund to guarantee small business loans — with half geared toward entrepreneurs of color.

- Set up a $50 million fund to give grants to mission-driven funds that focus on entrepreneurs of color.

- Collect demographic data for financial institutions and work to increase the diversity of bank executives, investors and other roles that oversee capital.

- Regulate the small business financing sector.

- Establish a public bank to reach more people usually shut out of traditional financial systems.

Nia Evans, executive director of the Boston Ujima Project, said it's important to find alternative ways to invest in diverse entrepreneurs.

"Let's get the resources that our businesses need into their hands and let's do so with trust and let's see what happens," Evans said.

Her organization, which invests in entrepreneurs of color, has pushed for a public bank. There are currently bills at the State House to establish such a bank.

With the state and federal governments allocating unprecedented amounts of aid to businesses during the pandemic, many people see this as a huge opportunity to reshape policies and create a better lending environment for entrepreneurs of color.