Advertisement

Boston Under Water

Boston’s Stormwater Problems Are Older Than The City Itself

As one of the oldest cities in the U.S., Boston is known for its rich history. But while many learn about Old Ironsides and the Battle of Bunker Hill, few know about the history under their feet.

And there’s a lot of history there. In fact, there’s a whole world of infrastructure underground that’s critical to making modern life work — subway tunnels, utility lines and, of course, the sewer system. In Boston alone, there are 666 miles of underground stormwater pipes that collect rainwater and channel it to Boston Harbor and elsewhere.

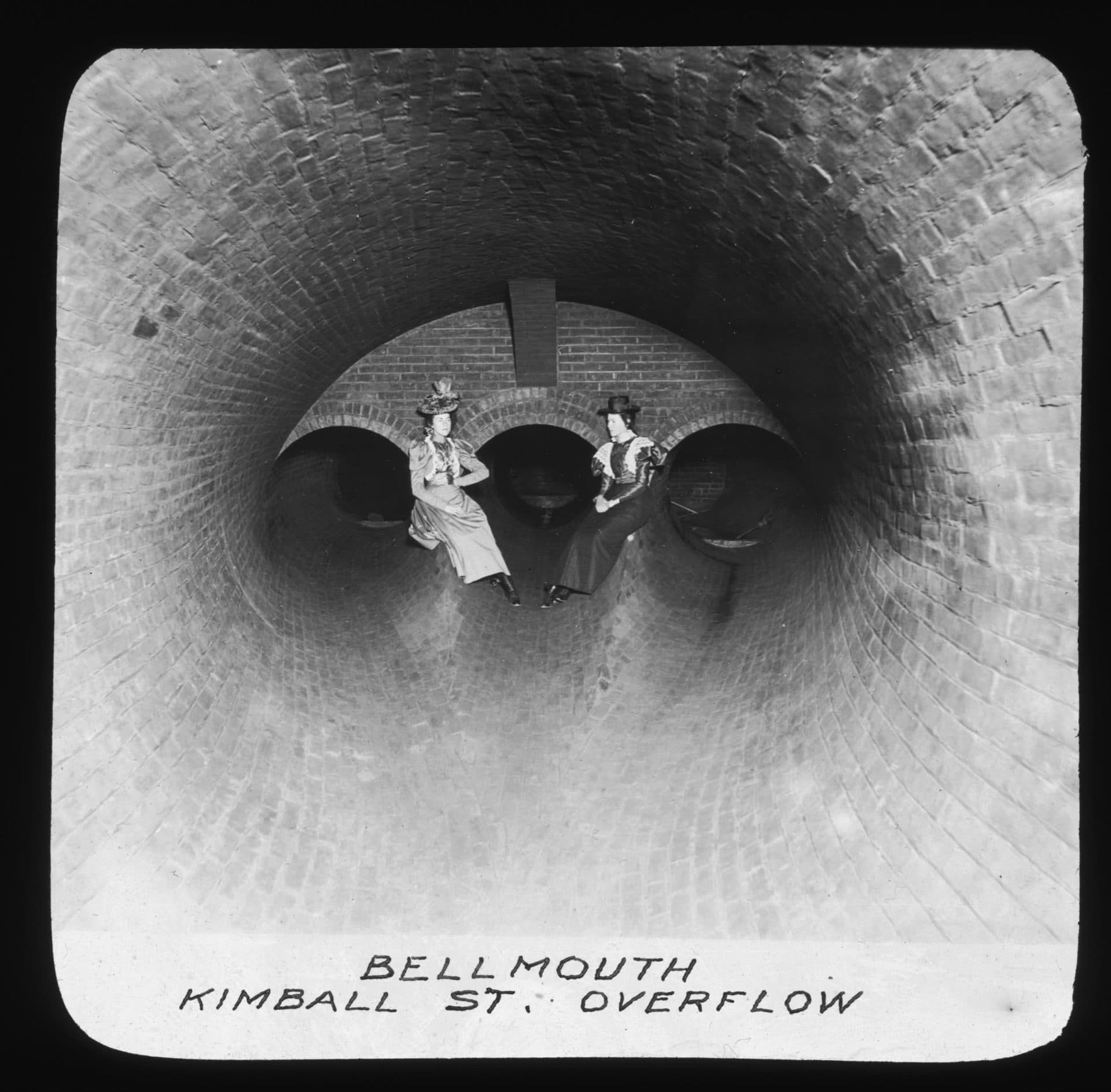

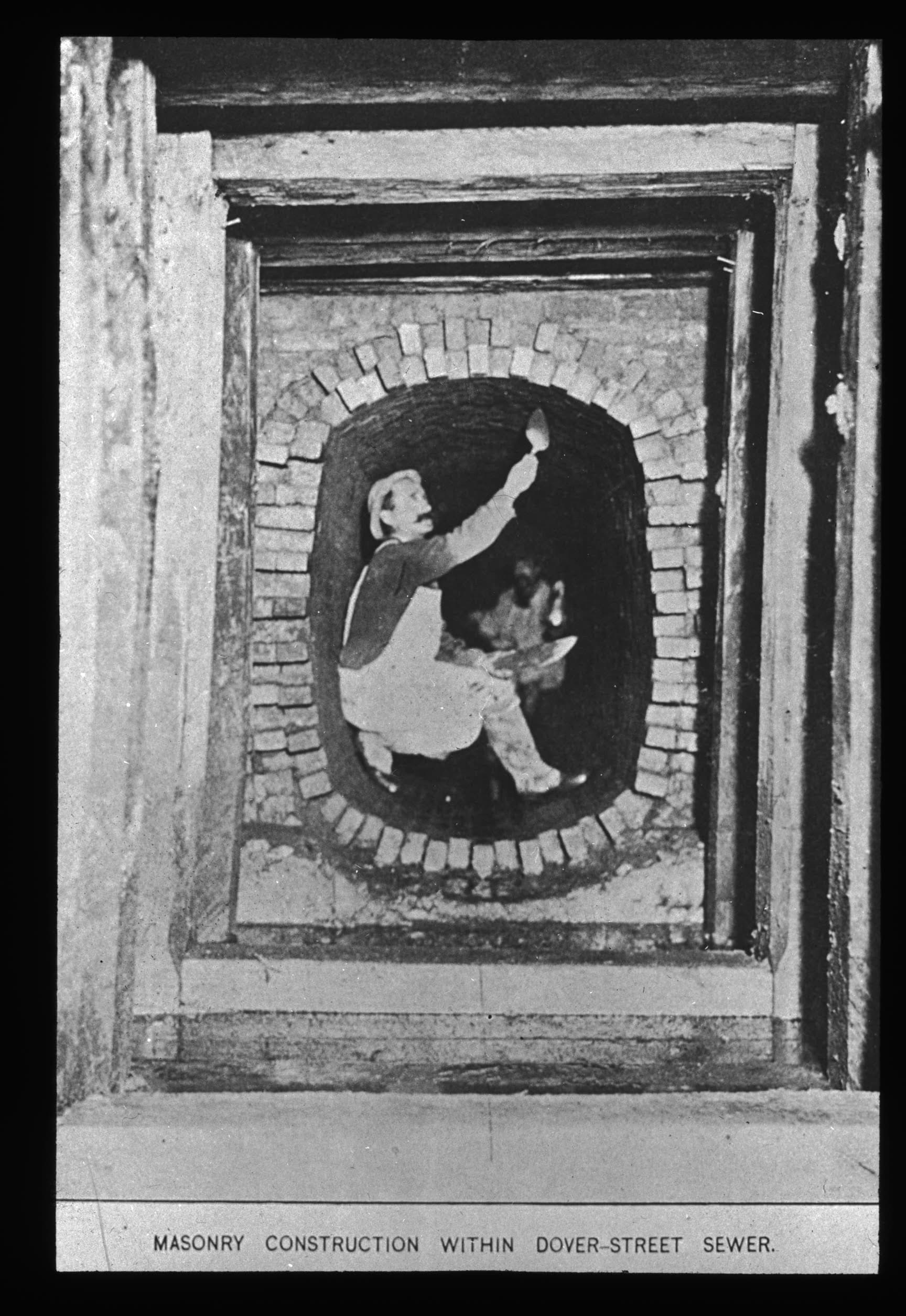

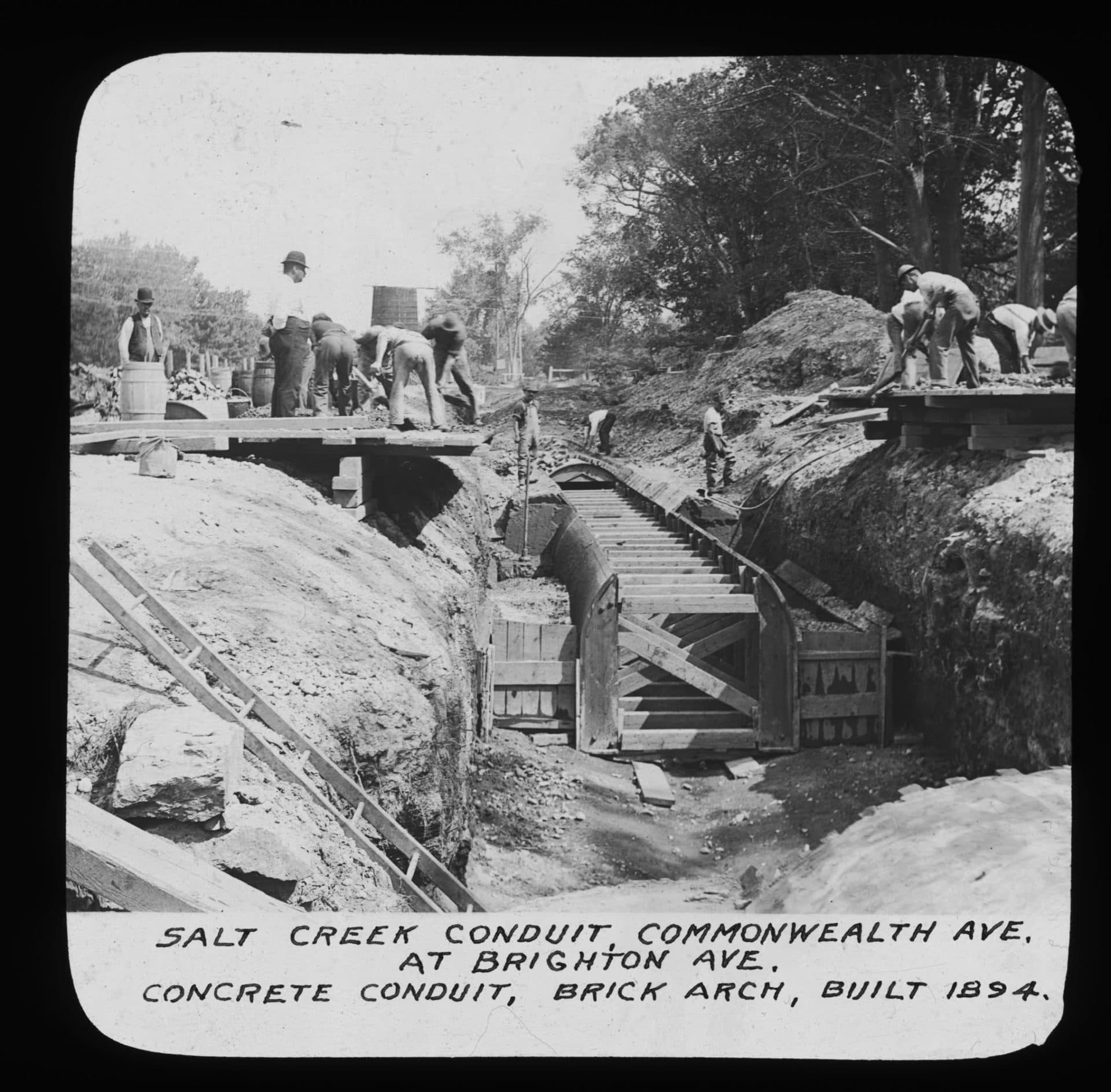

Nearly half of these pipes were built during the 1930s or earlier, and at least 120 miles predate World War I. That so many of these brick, cement and ceramic pipes are still going strong is a testament to the care with which they were built. And though structurally they might last another hundred years, they are simply not equipped for our climate future.

As part of our series “Boston Under Water,” we look at why climate change spells trouble for the stormwater system, and what the city is doing about the problem. (Read that story here.) But since so many of Boston’s water issues stem from its past, we thought it was worth exploring how the modern-day stormwater system came to be.

Plus, who doesn’t love reading about sewage?

Boston’s stormwater problems are older than the city itself. As European colonists began settling in the area during the 1630s, they quickly found that the clay-rich soil didn’t absorb water very well. City archeologist Joe Bagley says that when it rained, parts of the city could turn into a muddy “Slip-N-Slide.”

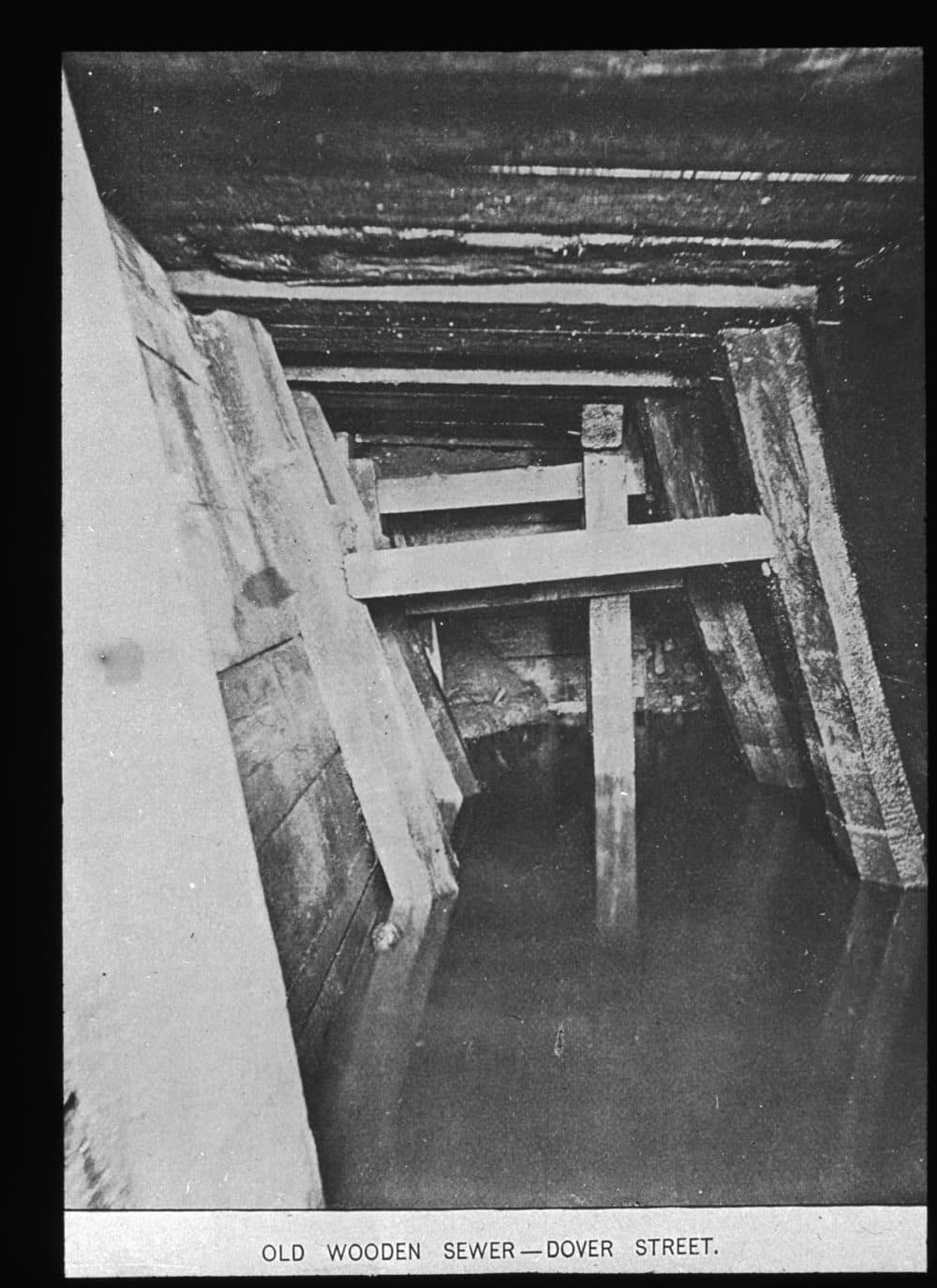

To remedy the problem, residents started digging up the cobblestone roads outside their homes and creating underground channels for runoff to flow to the harbor. These rudimentary “pipes” were constructed with brick and usually had slate bottoms and tops. (According to Bagley, people sometimes stole slate headstones from graveyards to cover the channels.) As more settlers arrived and built homes, the web of channels grew, and new residents began paying their neighbors for the privilege of connecting into an existing sewer line.

Over time, the constant construction became a sore point for residents, and in September 1701, the Town Council passed a rule declaring “that no person shall henceforth dig up the Ground in any of the Streets, Lanes or High-ways in this Town, for the laying or repairing any Drains” without permission. The cost of violating the order: 20 shillings. (40 shillings if you failed to pay within 10 days.)

Then there was the smell. Though 19th century Bostonians were technically prohibited from connecting their private privies (outhouses) to the rudimentary sewer lines, or dumping garbage and other waste into them, many did anyway. The result was a pervasive smell of rotting garbage and feces that hung over much of the city. It was said to be particularly potent by the waterfront and in the summer months; according to historian Nancy Seasholes, many residents openly referred to the Back Bay area as a “great cesspool.” (Perhaps even grosser: people with kitchen floor drains connected to the drainage pipes often had sewage smell wafting straight into their homes.)

Advertisement

The problem got worse in 1833 when the city officially allowed people to drain the liquid contents of their privies into the sewer system. The following year, the city went a step further and allowed residents to rig up a system to divert rainwater into the privy to help move sewage through the drains.

By the 1840s, more affluent residents were ditching their outdoor privies in favor of indoor water closets, a change made possible by Boston’s first municipal drinking water system. With clean water flowing from Lake Cochituate near Natick into homes through a 14-mile aqueduct, the rules about human waste in the sewer system went out the window, and people were actually encouraged to “flush” their toilets with this water.

Though the city’s drainage system was significantly bigger by the mid-19th century, there still wasn’t a ton of sophisticated engineering involved; the fact that it worked at all can be attributed to the hilly nature of the terrain and rainstorms that moved contents through the pipes. Still, drainage channels frequently clogged and backed up.

Sometimes trash blocked the sewers, but the bigger problem was that water couldn’t drain during high tide.

To make matters worse, even as the tide went out and wastewater began draining, it frequently didn’t make it very far before the tide started coming back in. (Being primarily fresh water, sewage also floated on top of the salty waters of Boston Harbor.)

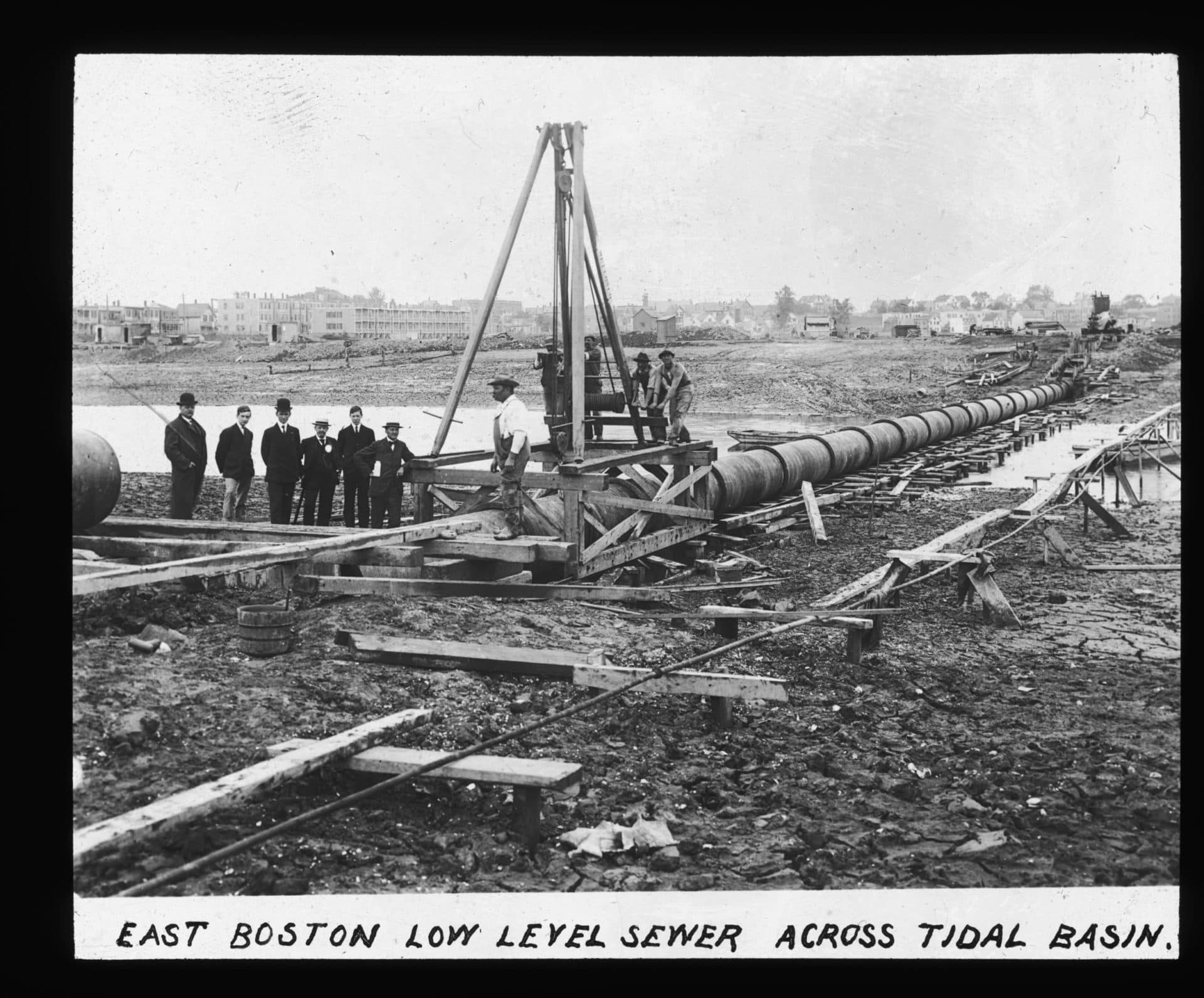

Boston’s growing population and expanding boundaries exacerbated these problems. Not only did more people mean more waste and stormwater runoff, but a larger city footprint meant extending existing channels to the new shoreline. (In 1869, Boston had 100 miles of underground sewer lines; by 1873, it had 125 miles.) Over time, it became harder to get the pipes to slope downward, so sewage traveled even slower through the system, exacerbating the smell problem.

In 1872, the problem of “bad odors” hit a tipping point, and in its annual report, the city’s Board of Health had this to say: “Large territories have been at once, and frequently, enveloped in an atmosphere of stench so strong as to arouse the sleeping, terrify the weak, and nauseate and exasperate everybody.”

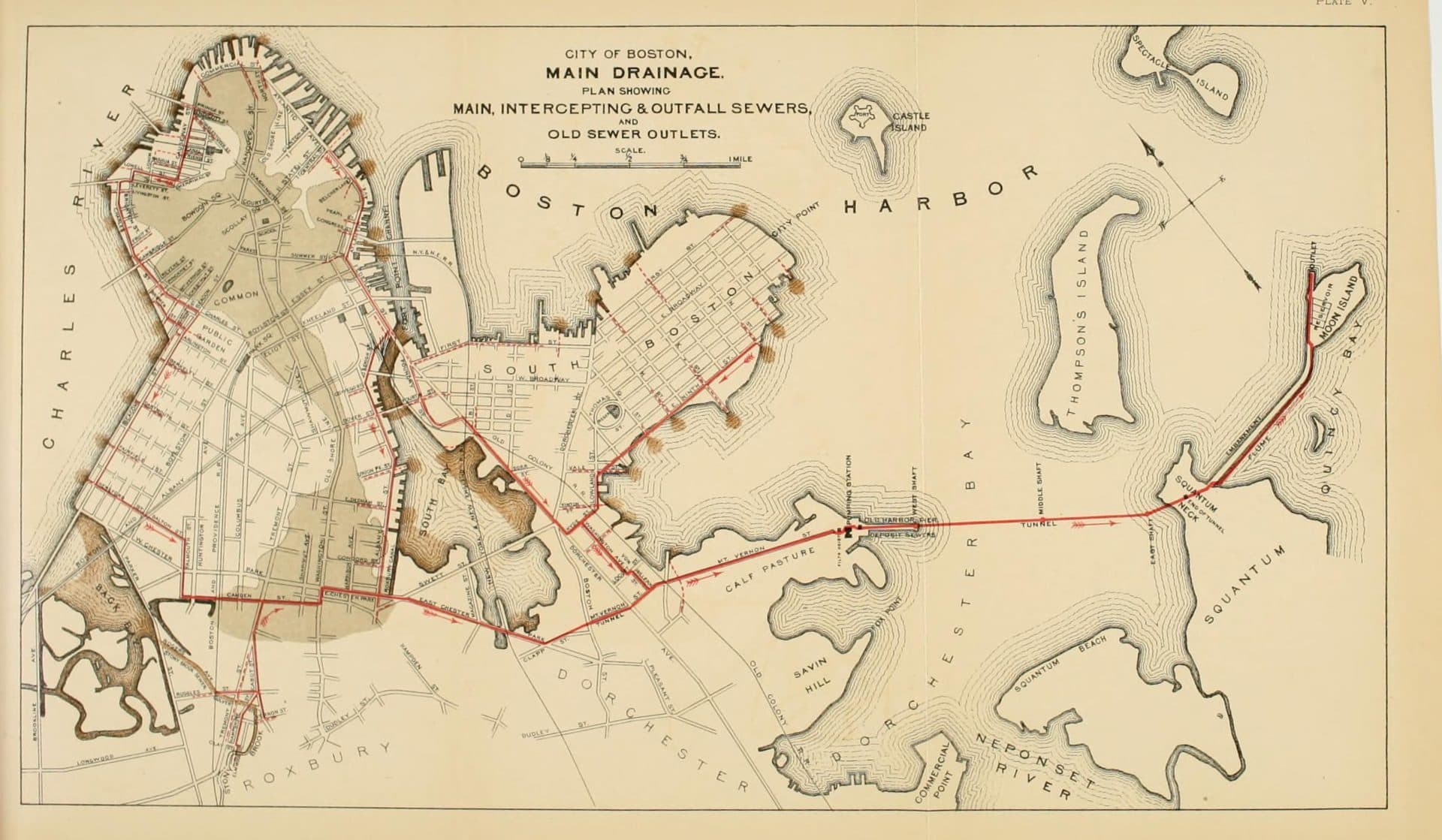

In 1876, the city authorized the construction of the Main Drainage, Boston’s first official sewer system. The main tunnel was made from brick and was about 10.5 feet in diameter, 3.25 miles long. It ran from a location near present-day Northeastern to present-day UMass Boston in Dorchester. At several points along its path, the line intercepted slightly smaller brick or cement pipes, which were connected to even smaller ones that drained from people’s homes.

At the end of the Main Drainage Line, close to where the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library stands today, engineers built the Calf Pasture Pumping Station — a coal-fired pump that raised the sewage 35 feet high so gravity could carry it another few miles through underwater pipes to Moon Island. To make the journey more efficient, the sewage was strained at the pumping station to remove anything solid. According to a city report from the time, commonly recovered objects included “rags, paper, corks, half lemons, lumps of fat, dead animals, pieces of wood, bottles, children’s toys, pocket-books.” (Human waste had usually disintegrated by the time it reached the station.)

After traveling under the Harbor, the effluvia drained from the sewer pipes into large above-ground reservoirs on Moon Island, where it sat until the tide went out and it could be let loose.

The Main Drainage system became operational in 1884, and a city report the following year noted that water near the city’s docks “once continually foul, has become pure, bad odors have ceased, and fish have returned to places where none had been seen for years.”

Though the city’s first modern sewer system was designed to move stormwater and sewage together — a so-called combined system — it wasn’t long before city officials decided to change course. In 1900, with the advent of small pumps throughout the system, rainwater was no longer needed to “flush” the sludge, so the city mandated that all new pipes be separate.

Fast-forward to today, and the skeleton of the 19th and 20th century sewer system in Boston still remains. The so-called West Side Interceptor, the large brick-lined pipe running under Beacon Street, is still in use, though the city has lined it with fiberglass. And while the contemporary system is obviously much bigger, more sophisticated and less ecologically harmful, the same big problem that plagued early Bostonians is once again on the minds of city planners — how to keep rainwater from flooding the streets?