The Blue Line Was Named For Boston Harbor. Now The Sea Threatens The Service

Tidal flats and marshland once surrounded much of Boston, swelling and soaking as the rain fell and tides ebbed and flowed. But over the course of the city's nearly 400 years, those sensitive areas were slowly filled in to make more buildable land, leaving just 200 acres of wild marsh along the border between Boston and Revere.

It's here at Belle Isle Marsh that the future of the Blue Line could be determined.

On a recent afternoon, Julie Wormser, deputy director of the Mystic River Watershed Association, walked through Belle Isle, an ecological oasis and rare urban wild in Boston.

The marsh protects the Orient Heights Car Yard — as well as a T stop and an electrical substation — from the nearby ocean, defending all that infrastructure from storm surge. Without the marsh, Wormser said, this section of the Blue Line would be far more vulnerable to flooding. But, as sea level continues to rise, the marsh may disappear under water.

"If you have open ocean headed right for the Blue Line, it gets destroyed much, much faster than if that ocean hits the marsh first," she said. "All that power gets dissipated through hitting vegetation and mud."

The MBTA Blue Line is one of the most important transit links in the region, connecting the North Shore with downtown. In 2019, it carried almost 70,000 people a day from East Boston and Revere to Boston. During the pandemic, the line saw the lowest drop in ridership across the T, pointing to its significance to essential workers. The line will only become more important in coming decades, with a massive new development underway at Suffolk Downs, and a renewed proposal to build a Red-Blue Line Connector near Mass. General Hospital.

Traducido en español por El Planeta Media.

But the T says the Blue Line faces a growing threat from the ocean. A recent study on the Orient Heights Car Yard found that, by 2070, the entire facility would be under several feet of water during a so-called 100-year storm. And other stations along the line, as well as the mile-long tunnel under the harbor, are also at risk of flooding.

"The Blue Line is extraordinarily vulnerable, the most vulnerable of our rapid transit lines to sea-level rise," said Hannah Lyons-Galante, the MBTA’s climate change resiliency specialist. "It is the lowest lying line — it's really a function of the landscape that it travels through, they are all areas of filled land in Boston. And so it's not just the Blue Line, but also the communities that it's surrounded by."

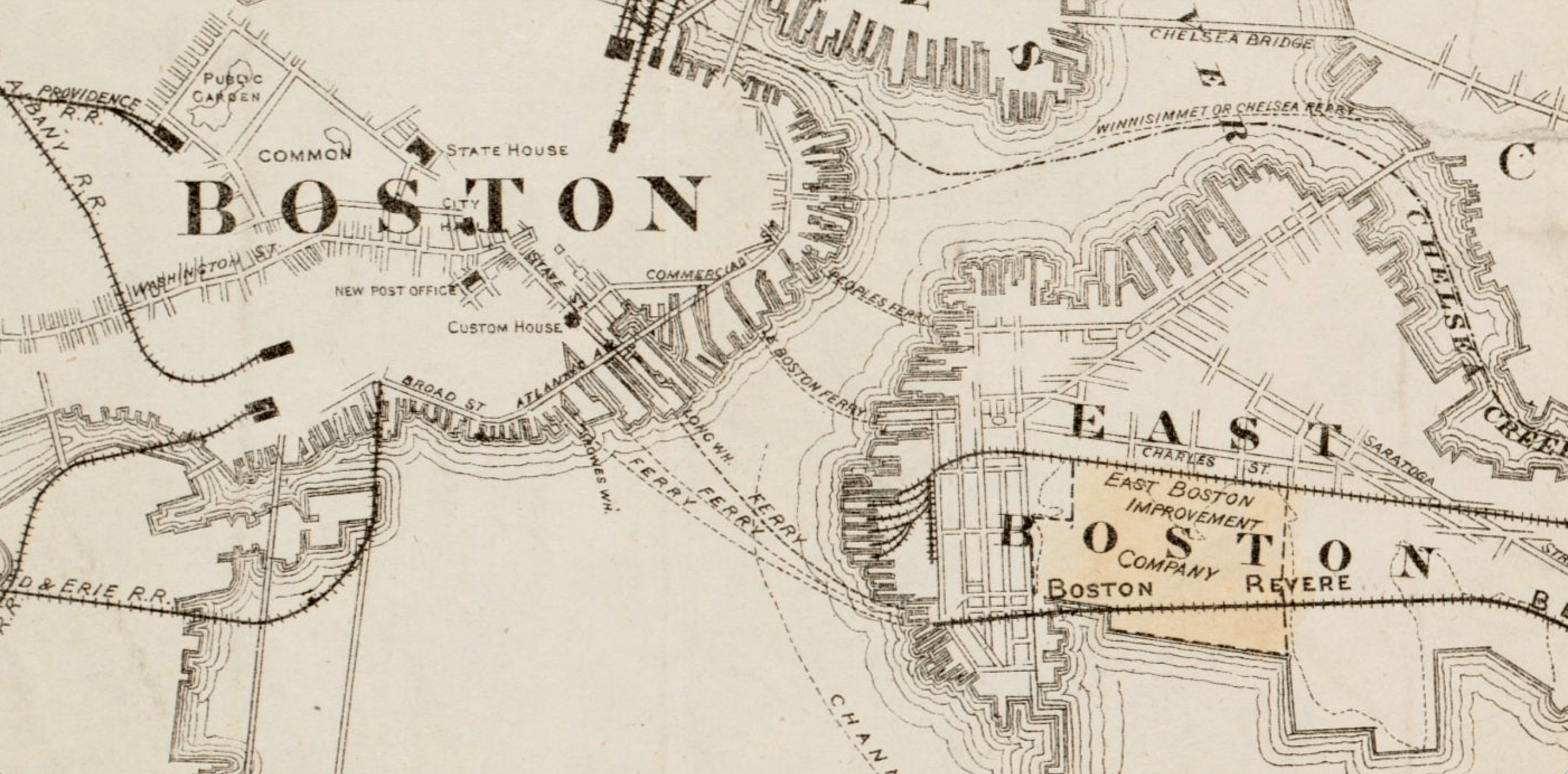

The Blue Line was built to connect the immigrant-heavy population of East Boston with the labor-thirsty industries downtown. The centerpiece was the mile-long East Boston Tunnel under the harbor, completed in 1904. The first underwater subway tunnel in the United States, it took more than two years to build, and four workers died in the process.

More than 120 years later, the Blue Line still matters to the legions of workers who commute through Maverick Station in East Boston, through the harbor tunnel to Aquarium Station downtown.

They come from around the North Shore to catch the train to their jobs at the airport or downtown, or to connect with other parts of the city.

Dora Mendoza, a Salvadoran East Boston resident who works at a supermarket, has been riding what she calls “la línea azul” six days a week for 17 years.

"The Blue Line is very important to all the people who have to travel by train," Mendoza said in Spanish. "And we’re thousands of people who do this — I don’t know what we would do if it wasn’t for the Blue Line."

Milton Souza, originally from Minas Gerais in Brazil, lives in East Boston and works as a landscaper at Harvard University.

"I ride the Blue Line every day — and it's very good for me,” Souza said in Portuguese. “I don’t have a car — I don’t need one. The Blue Line takes me where I'm going and brings me home every day."

When Hurricane Sandy flooded 11 New York City subway tunnels, including the six connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan, it set off an alarm for planners and activists in Boston.

"If we don't plan right, then [Sandy] will happen here," said Phil Giffee, who heads the East Boston nonprofit Neighborhood of Affordable Housing. "We know the seas are rising ... there's a worst-case scenario that could easily happen. And Sandy almost did happen here."

Giffee said the Blue Line in its current form should be protected.

"Unless everybody has a kayak and a canoe and can swim 500 yards in the middle of the winter, I don't see another way of getting [downtown]," he said. "It does need to be preserved for the economic way of life that connects us to three other systems, which branch out and go to throughout metropolitan Boston."

Unless everybody has a kayak and a canoe and can swim 500 yards in the middle of the winter, I don't see another way of getting [downtown].

Phil Giffee

The MBTA knows it has a problem: officials say the entire rapid transit system is “extremely sensitive” to the threat of severe weather and coastal flooding.

But not everybody agrees that shoring up tunnels built at the turn of the 20th century is a good idea in the era of climate change.

Julie Wormser of the Mystic River Watershed Association believes underground infrastructure will have to be replaced — not just the Blue Line, but everything below grade.

"We had flooding that affected the Aquarium T station something like 22 times a couple of years ago," Wormser said, referring to the winter storms of 2018. "And that's only going to get worse as our chronic sea-level rise increases."

"When you really think about sea-level rise, it means coastal retreat," she added.

Wormser credits the MBTA for facing the risk of coastal flooding head-on. But she says we need to start considering a post-Blue-Line future — and she thinks rapid bus transit is the way to go.

Lyons-Galante said the T is committed to protecting the Blue Line — not by raising the infrastructure out of harm’s way, but by building barriers to keep the water out. The MBTA has already begun floodproofing the Aquarium station, for instance, awarding a $1.7 million contract to add new floodgates and repair water-damaged concrete and corroded tracks, among other upgrades.

Still, Lyons-Galante recognizes the threat of sea level rise could force change.

"If, at some point, all of this becomes completely unfeasible — we suffer damages that are so expensive you cannot repair them — you have to adapt," she said.

But "it is not our intention to change anything about the Blue Line, because we already have something that works and functions right now.”

Other advocates say instead of trying to keep the water out, we need to start adapting to the idea of a wetter Boston. That could mean investing in more ferries between East Boston and downtown — the way people got back and forth before the Blue Line tunnel was built, over a hundred years ago.

This segment aired on June 15, 2021.