'We Can Talk About This': Kids Benefit When Parents Open Up About Mental Health Struggles

Even before the pandemic, Ana Groves was well aware that working full-time and raising three kids was challenging.

"I feel like I'm always just running around with my head cut off trying to do everything," Groves said of her life in suburban Foxborough.

With the pandemic, came added responsibilities: monitoring her kids' remote learning and helping them adjust and feel safe. All of which triggered some difficult emotions.

"I had a lot of anxiety, a lot of stress, a lot of guilt," Groves said. "Just always thinking: 'Am I doing enough for them? My teenager, is he sleeping 'til noon? How is that going to affect him?' "

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cite a 2021 study estimating that one in 14 children has a caregiver with poor mental health. Some recent surveys of parents suggest that as many as half experienced worsening mental health during the pandemic. The most common issues are depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress.

For Groves, navigating the pandemic with her 8-, 14- and 17-year-old children became increasingly overwhelming.

"I think the pandemic pushed me over the edge," Groves said. "I was already just hanging on by a string."

In March of 2020, as the virus began to take hold in the U.S., Groves' eldest son was placed in a therapeutic boarding school after years of being in and out of psychiatric hospitals to treat Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Groves was used to the challenges that come with caring for a child with mental health issues.

Advertisement

She said there were periods of time over the last few years — usually about "a good six months," where she said her son would be fine living at home, but eventually, his mental state would decline.

"I think the pandemic pushed me over the edge. I was already just hanging on by a string."

Ana Groves

"That includes self-injurious behaviors," Groves explained. "He can get pretty aggressive, and that's not him at all. But he can get aggressive with others. He's destroyed furniture."

Pandemic-related restrictions prevented visits to her son's new school, so it made it difficult for everyone to acclimate to his new placement. She wanted to see her son, and his siblings wanted to know that he was OK. Groves said trying to feel connected and keeping the kids feeling safe during COVID, while taking precautions, was a tough balancing act.

Talking To Kids About The 'Feelings Doctor'

Last fall — with no end of COVID in sight — Groves took a 12-week leave from her teaching job to help her and her children adjust, but after returning to work, she still felt overwhelmed.

"I ended up going to my primary care [doctor] in February and said, 'I just, I am not handling anything,' " Groves said. "I broke down in her office."

The doctor prescribed medication. And Groves started seeing a therapist, or what her 8-year-old daughter, Kate, calls "a feelings doctor."

"It's a doctor you go to to talk about what you're feeling and thinking," Kate explained.

Because of their sibling, Groves said her kids already understood the importance of mental health, so she has been open with them about what she's going through. Kate said she might want to talk with a "feelings doctor," too. The isolation of the pandemic has made her sad, and she might like to talk more about what she's experienced.

"My friends," she explained. "Like, if their parents tell them they can't have a play date or something with other people, and they can't go out of the house."

Many children's mental health experts say what Groves is doing is exactly right: communicating about her own struggles and making mental health issues part of every day life.

"I think that's such a great way of explaining developmentally appropriately to an 8-year-old ... a 'feelings doctor,' " said Dr. Chase Samsel, medical director of the Psychiatry Consultation Service at Boston Children's Hospital. He added that being forthcoming with kids increases the likelihood that they'll reach out for help to process difficult emotions, too.

"Families should come back together and say, 'Listen, we can talk about this,' and 'This happens,' and normalize emotions in difficult times and show that we can still move forward," Samsel said. "We can still be OK."

How Caregivers' Actions Affect Kids

How a caregiver's mental health ripples down to a child largely depends on the family's response and circumstances. The greater the adversities — such as financial hardships, or the illness or death of a loved one — the greater the likelihood of mental health issues.

"There's some really profound consequences for kids who are constantly feeling that sense of threat and not getting the support that they need from caregivers who themselves are either absent or overwhelmed."

Dr. Heather Forkey

In a large-scale crisis like a health pandemic, many caregivers tend to focus on the wellbeing of kids. But many experts stress that when crisis strikes everyone, parents need to prioritize getting support for themselves.

Dr. Lovern Moseley, a psychologist at Boston Medical Center and CEO of Empowerment Counseling in Stoughton, says doing that will help caregivers better gauge their children's health, help kids feel safe and provide a model for how to seek help.

"This has been a very abnormal event, and we can't apply the same coping strategies that we may have had in the past," Moseley said. "So that means that parents have to look at how to take care of themselves first, and that's going to be the thing that's going to help to benefit their child."

While children typically experience the same mental health issues as adults in a crisis, several pediatricians say the symptoms might be different — especially in younger kids. They advise watching how kids play to observe if they're behaving aggressively or having trouble with daily tasks, like eating or sleeping. For older kids and teens, the symptoms may resemble rebellion and anti-social behavior.

Long-term exposure to stress affects the brain's physiology — especially for developing brains, according to UMass Medical School pediatrics professor Dr. Heather Forkey. The body responds to threats by overstimulating the parts of the brain that seek safety, while turning off the parts that allow for higher-level thinking. Forkey says that could affect kids' ability to focus, organize information, and ultimately, impact their physical health.

"So there's some really profound consequences for kids who are constantly feeling that sense of threat and not getting the support that they need from caregivers who themselves are either absent or overwhelmed," Forkey said. "In a very primitive way, we're animals, and we're responding the way we were designed to respond.

"Recognizing what that physiology is," she added, "and working with it, instead of against it, would be to our advantage."

As director of the Child Protection Program and Foster Children Evaluation Service at UMass, Forkey sees a lot of vulnerable families. She says children who are not well supported by caregivers are more likely to have adverse childhood experiences. Several studies have linked this to an increased risk of mental and physical health problems into adulthood.

Research from other large-scale disasters, such as hurricanes or 9/11, shows that close to half of children have some type of initial reaction, like depression or anxiety. But the effects of a more than year-long pandemic are still unknown.

Resiliency Can Be Built

Lili Lengua, a University of Washington professor partnering with Harvard researchers to study the mental health of children during COVID, estimates that the number of kids with behavioral and mental health problems will double because of the pandemic.

"For youth, in some ways, we can think of it as a double jeopardy or a double whammy from the pandemic," Lengua says. "Not only are they and their families experiencing stress, but if their parents have their emotional or mental health disrupted, that, in turn, probably disrupts their ability to support their children."

The good news, Lengua said, is that research suggests most kids can be expected to bounce back. And while nearly everyone has experienced some degree of discomfort during COVID, that does not mean that every problem is a mental health issue.

"We've been through a difficult time, but difficulty doesn't mean that we all have a mental health disorder," said Melissa Brymer, director of terrorism and disaster programs at the UCLA-Duke National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

"We've been through a difficult time, but difficulty doesn't mean that we all have a mental health disorder."

Melissa Brymer

Brymer said support can come in many forms — connecting with communities, establishing familiar routines and perhaps getting directly involved with projects that help others as society makes its way out of the pandemic. Support for some may involve trying to move on quickly, while others may need to take more time, for example, to acknowledge the loss of loved ones and livelihoods.

For Foxborough mom Ana Groves, "bouncing back" will be a process. She plans to keep seeing a therapist, exercise regularly and be involved with parent support groups. But for her, the pandemic has left a permanent mark.

"I'm a happy, smiling person, and it's changed me for sure," Groves said. "I'm struggling on a daily basis to just find the good, you know?"

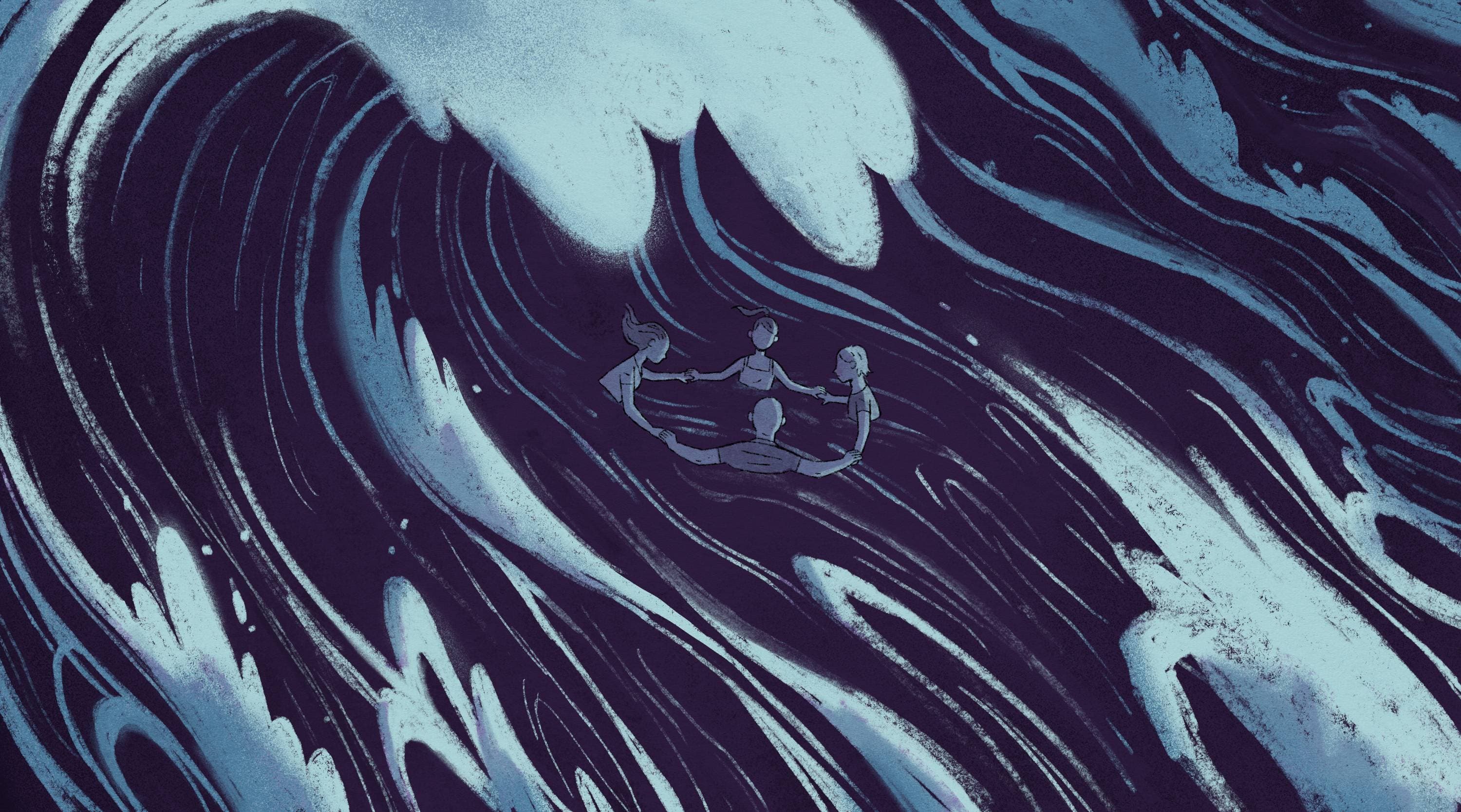

This project is funded in part by a grant from the NIHCM Foundation. Illustrations and animations in this series were created by Sophie Morse.

This segment aired on June 23, 2021.