Advertisement

Review

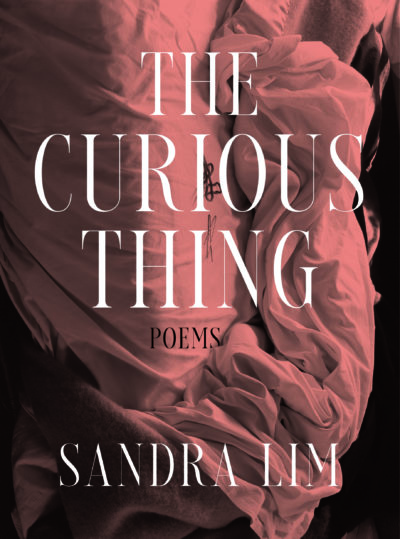

Sandra Lim Ponders Unanswerable Questions In Poetry Collection 'The Curious Thing'

In the early 20th century, the composer Charles Ives produced a piece of program music titled “The Unanswered Question,” in which a plaintive, solo trumpet repeatedly poses “the perennial question of existence.” Each time, it is answered by a jeering quartet of atonal woodwinds whose musical phrasings become increasingly chaotic and dissonant with each call and response. Eventually, both sides of the dialogue give up. All the while, a bed of strings drones on beneath the action, utterly unmoved by the frustration and angst that has played out above it, like the soft hum of a cold, indifferent universe. The question is never answered; in the end, it’s as if it was never asked at all.

In her provocative third collection, “The Curious Thing,” (out Sept. 14), Cambridge-based poet Sandra Lim asks all sorts of questions; many go unanswered, some are unanswerable.

Can you still be afraid then, for what you don’t have and what you’ll never have? (“The Future”)

What form does [my body] take without the soul? (“That Are”)

What happens to the old love, tell me if you know. (“The Beginning of Spring”)

Amid the lack of resolution, we’re left to ponder the limits of words, whether they can ever truly measure up to the feelings they’re meant to represent, and the futility of expression when true meaning is elusive — or illusory. Like Ives’s trumpet, these poems cry out for answers, but Lim clearly expects no response. Instead, she revels in the yawning silence.

The futility of understanding is a recurring theme throughout Lim’s poems. In “Pastoral,” things are “beyond” understanding; in ”The Future,” understanding is depicted as a kind of “despair.” In “The Beginning of Spring,” it becomes an example of hubris:

I have never been here before and yet I thought I understood it all.

But Lim wisely observes that understanding is not always necessary to make a connection or resolve an ambiguity. Knowing and feeling are not the same thing, but they can be equally conclusive. From the second of two poems titled “Pastoral”:

...and though at the time I could not understand what he was saying, the sentiment landed, and it was like a head hitting the stone tiles of that patio...

Ultimately, there is only one thing worth understanding, Lim writes in “The Future”:

There are no origins

or general principles.

There is only this hole in the earth.

Memento mori, then. Death is the only truth, and the grave stands as the universal answer to all questions. It is a clarifying certainty that makes the search for some other answer seem like sheer denial.

Despite all this, “The Curious Thing” is not a nihilistic work:

Part of what makes life shameful and exciting

is the fact of being gripped

by something true that you just barely intuit

If we had the answers to all our questions, Lim proposes, wouldn’t that just spoil the fun? Lim delights in that ineffable force that lies just beyond articulation, in the spaces between thoughts or in stolen glances. These are the moments at risk of being obscured by an overbearing focus on the past, or fear of the future.

In “Boston,” Lim writes of a youthful relationship:

...I didn’t love him.

But I very much wanted someone to look at me,

in all my youth and feminine momentum.

The speaker seeks not to be understood, but rather to be beheld in a fleeting, flickering moment she feels epitomizes her. The poet implies a distinction, or perhaps even a conflict, between the meaning of a thing, which is bound up in self-conscious analysis, and what something really is, which is to be sensed, felt, or perceived. It’s a curious thing, indeed.

In her simplest, and perhaps most effective, poem Lim imagines a story with two endings and refuses to pick one. “Do you hear me?” she asks. The question can be read as either pleading or defiant. Perhaps it’s both. But there can be no rebellion against the singular ending, despite what the speaker might wish. In just six lines, this poem, “Endings,” is able to draw on so many different, conflicting emotions — anger, anxiety, sentimentality — without being overwrought or excessive in its language. Lim’s touch is light, but her impact is anything but.

Lim opens the collection with an epigraph from Renoir, which says that we must let ourselves go along in life “like a cork in the current of a stream.” The austere, koan-like poems of “The Curious Thing” bring us into a frame of mind where we can worry less about finding answers to the big questions of life, such as why the current is dragging us along, and instead rely on our intuition to suss out and better navigate its unpredictable swirls and eddies.