Advertisement

Review

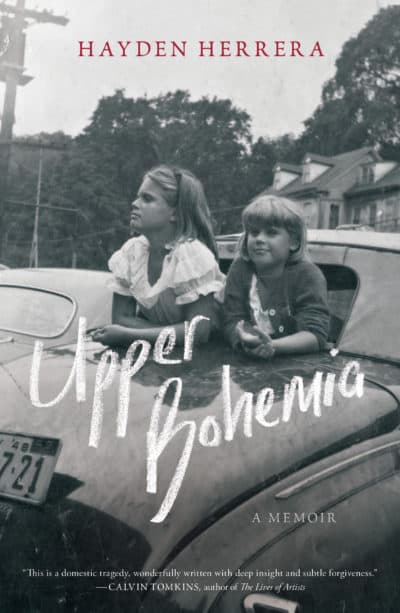

In Memoir 'Upper Bohemia,' Hayden Herrera Recounts Her Chaotic And Artistic Upbringing

In “Upper Bohemia,” Hayden Herrera offers a richly detailed account of her artistic and chaotic upbringing in the 1940s and 1950s, in multiple households ranging from Cape Cod to New York to Mexico. It is a tale with such obliviously careless parents, it may make you appreciate anew all the boringly steady moments your parents might have created for you.

Narcissistic though her parents were, they did instill a great love of art and nature in Herrera and her older sister Blair. An art historian, Herrera has written biographies of artists and sculptors including Mary Frank, Isamu Noguchi and Henri Matisse. Her biography of Frida Kahlo was adapted into the 2002 movie “Frida” starring Salma Hayek. Her biography of early 20th-century painter Arshile Gorky was a finalist for the 2004 Pulitzer Prize.

Herrera’s parents, Elizabeth Cornell Blair and John Charles Phillips, each came from families with roots sunk deep in American history. Her mother’s great grandfather founded Cornell University. Her father’s ancestors founded Phillips Exeter Academy and Phillips Andover Academy. Herrera notes that her self-assured parents, raised in great wealth, “did not have to earn confidence by achievement. Self-esteem was bestowed upon them by birth.”

The memoir’s title is drawn from her mother’s term for herself and her friends, “upper bohemians,” who came of age in the late 1920s and rebelled against a traditional and materialistic way of life. Herrera’s reaction to being raised in upper bohemia was to build a safe, dependable life for herself and her own family.

For her parents, nurturing their two daughters placed a distant second “to the leading of a passionate life,” as Herrera shows again and again. Both parents were artists, and their priorities were to be well-read and well-traveled, and to live in harmony with nature. An upside of this reverence for nature is that Herrera spent most of her childhood summers swimming and exploring the expansive acres of their family’s coastal land in Wellfleet and Truro on Cape Cod. Her father had designed and built a large, spartan home for their family, and built smaller cottages to rent out.

Their list of friends and party guests reads like a mid-20th-century who’s who of artists and writers. They included literary critic Edmund Wilson and writer Mary McCarthy (who would satirize members of the Cape Cod group, lightly disguised, in her 1955 novel “A Charmed Life”), and artists Roberto Matta (whom Herrera calls Matt Echaurren), Robert Motherwell, and Max Ernst and his wife Peggy Guggenheim.

Advertisement

To Herrera, her parents seemed a beautiful god and goddess. Her father could build or fix anything; her mother was fearless and adventurous. Herrera notes that even in their community, where people regularly went to the beach in the nude, her parents “were so secure in their physical attractiveness that they were known to walk to a neighborhood cocktail party and mingle without clothes.”

After their parents’ divorce in the 1940s, the sisters ping-ponged between their various homes and an ever-changing set of new stepfathers and stepmothers. By the time she was in eighth grade, Herrera had attended eight different public and private schools in Massachusetts, New York, Mexico and Vermont. At a young age, she remembers training herself “not to miss the people I was not with.” Both sisters battled weight issues into their teens, due in part to their parents’ haphazard dining habits, and in part to the stress of constant unpredictability. With so few adults to count on, Hayden often relied on her older sister as protector and guide.

Darker moments for the sisters were often lightened by adventure, such as their extended stays in different Mexican towns, or by stretches of stability, especially when they lived with their paternal grandmother in her large, well-run home in Cambridge, just outside of Harvard Square (guests at their grandmother’s formal dining room table included poet Archibald MacLeish and historian Arthur Schlesinger).

Herrera has a fine eye and impressive memory for period details — the layouts of different homes in which she lived, the weekly ice delivery for the icebox, her neighborhood on East 85th Street “connected by laundry lines.” But too often, she unfurls her life more as a timeline than a narrative, with consequential and trivial events rendered in the same tone. I often wanted the storytelling to slow down, to allow her adult voice to provide more perspective on her younger self. When Herrera does give traumatic events the space they deserve, they carry a powerful impact.

As one example, some of the men her mother partnered with possessed an initial warmth that masked a terrifyingly short temper, keeping the sisters on constant alert for mood swings. Even worse, one of the stepfathers sexually abused both young girls. With parents who were not physically affectionate, Herrera states that she “had no idea what was or wasn’t normal.” She did not mention the abuse to her mother until she was in her 30s. In a response revelatory in its coldness, her mother dismissed Hayden’s trauma by saying “Oh, that kind of thing happens to everybody. It happened to me with my father.” In a few well-chosen sentences, Herrera was able to show the horror of the abuse, the isolation it caused then and later, and her mother’s blinkered world view.

When Herrera ultimately describes her own adult life in contrast to her upbringing, she is able to frame her life and her parents’ later lives in thoughtful, forgiving and accepting ways. When it came to her own marriage, she was determined, when she became a mother, to raise her children in a style as consistent as it was loving.