Advertisement

Mass. Locked Up People With Mental Illness For Decades. Now Advocates Want Their Stories Told

Resume

Traducido en español por El Planeta Media.

For many years, people with disabilities and mental illness in Massachusetts were locked away in state institutions to be kept separate from the rest of society.

Now some advocates and families are pushing to create a commission to reckon with the way patients were treated and the abuses they endured.

"There is no formal statement of what the state schools and what the state hospitals were or why they came to be, what they were, how they closed," said Alex Green, a Waltham resident and Harvard public policy lecturer who is spearheading efforts to establish the commission.

Green said he wants the unvarnished history to be told, as he walked the grounds of the long shuttered Metropolitan State Hospital where Belmont, Waltham and Lexington come together.

Closed in 1992, many of the buildings have either been torn down, or converted to housing or businesses. But the brick administration building, covered in graffiti and invasive vegetation, stands abandoned, a stark reminder of a system that at one time was made up of 27 state hospitals and state schools, where thousands were sent away, including many who complained about mistreatment over the years.

For Green, his quest is personal. He lives with mental illness. And had he been born a few decades earlier, Green believes he might have been sent to an institution himself.

Green says the surviving written records are likely scattered all over the state.

"When these places closed, people just kind of threw boxes in trucks and sent them to the archives or wherever they could. And I think walked away for a lot of different reasons," Green said. "And I think that people deserve more closure than that."

He says time is running out, however, as there are fewer residents left alive each year.

One of those residents is Patricia Brown, who was sent to the state-run Walter E. Fernald School in Waltham 62 years ago when she was only 8 years old.

"I remember I went out there in the fall and it was scary. I didn't know what was going on," said Brown, who is now pursuing a G.E.D at the age of 70.

Brown and her brother were sent to Fernald by a judge, who deemed their mother unfit.

She says Fernald was a hard place to grow up.

"A lot of children died. I've seen them die right in front of me. And I couldn't understand why. It was a lot of abuse. It's sad, it's very, very sad," Brown said.

Not all abuse resulted in death.

About a decade before Brown arrived at Fernald, 74 boys there were enticed to join the school's Science Club.

Club members were offered oatmeal for breakfast.

But unbeknownst to the boys, the oatmeal was laced with radioactive material. It was part of an experiment conducted with MIT and Quaker Oats to learn whether the cereal inhibited the absorption of iron.

Patricia Brown says girls at Fernald endured other atrocities.

"They raped girls, they molest girls," said Brown, referring to unnamed Fernald staffers at the time.

"They drug you up and they molest you. And that's the truth," Brown said. "A lot of girls got pregnant. Fortunately, I didn't get pregnant, maybe because I was fighting."

Brown says that fighting back often resulted in being locked away, alone in a basement.

Abuses, like the ones Brown described, prompted the federal courts to intervene in the 1970s, and order the state to improve conditions at the institutions.

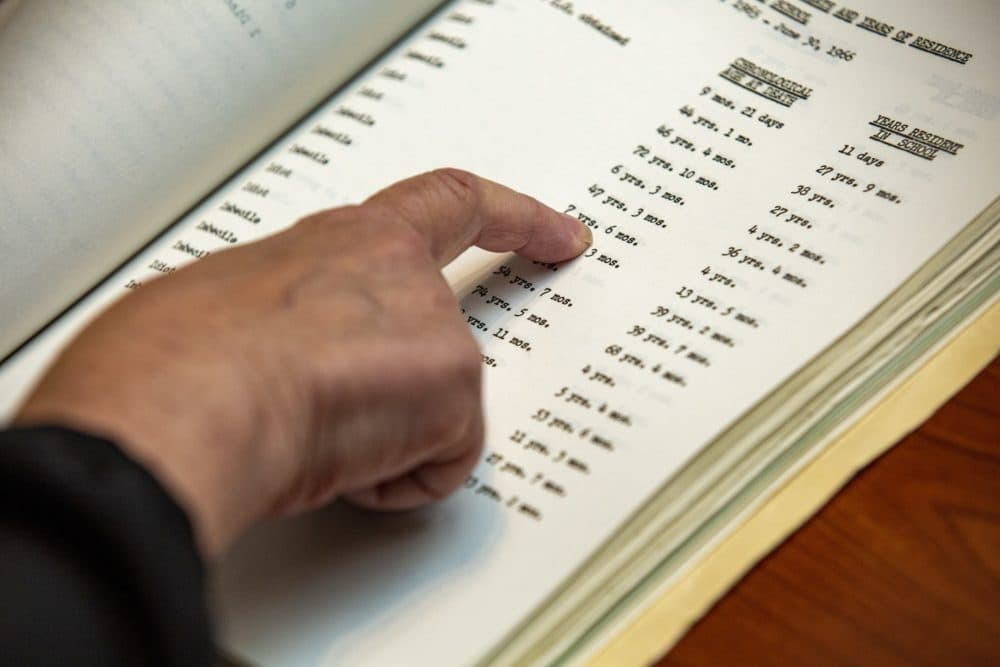

One of the objectives of the commission would be to identify records that could be made available, including those at the Massachusetts State Archives in Dorchester.

Laura Zigman, of Cambridge, traveled to the archives to find out more about her oldest sister, Sheryl.

Sheryl Zigman died at the age of 7 while a resident at the Fernald School in 1965. She suffered from intellectual and physical disabilities due to a rare disease.

"I've just gotten really curious just about the most basic aspects of her time there and when she went there and how long she was there," Zigman said. "My parents are both gone. So I'm reliant on trying to piece together things."

Archives staffers were able to show Zigman some records about the institution, but nothing about her late sister, Sheryl.

For that, she would need a court order — even though Zigman is the next of kin.

"I could end up going through a lot of hoops and then they could say there are no records. You know, there was a flood. I mean, who knows?" Zigman said.

Supporters say a commission would be able to streamline the process for accessing patient records.

Other proposals would make the records publicly available after 90 years.

The bills are slowly making their way through the Legislature. A public hearing on the commission bill was held in June. But the legislation is not a high priority so it may take a while before a vote.

Co-sponsor Sen. Mike Barrett, of Lexington, says it's important that we deal with all the injustices that might have been meted out.

"Each of these institutions, and we count 27 of them spread throughout Massachusetts, have a story of their own," Barrett said. "And the human beings who were domiciled there, often without what we would now consider to be their civil rights, deserve to have their stories told," he added.

Some former employees of the institutions also favor a commission.

Among them: Steven Iannaccone, who worked at Fernald for 24 years, beginning in 1976. That was a year after the state signed a consent decree to improve conditions at the institutions.

Iannaccone acknowledges conditions were poor prior to the consent decree, but also says there were a lot of dedicated employees who improved the conditions over time.

He recalled one patient who initially was constantly yelling and refused to wear clothes, but later was functioning well enough to eat at restaurants.

Still, he thinks people should be able to see the full history of what happened — "the bad and the good."

Back on the grounds of the former Metropolitan State Hospital, Green says it's also important the commission include people with disabilities — people like him who might have been locked away in institutions years ago.

"It's about making sure that people who were erased in the first place are not erased in the process of uncovering this history," Green said. "And I think in that, that's why there's such a big push in such a central component to this, that it has to be led by people with disabilities. The commission has to be a majority of people who identify as being disabled."

But for now, the commission remains just an idea, waiting for Beacon Hill to decide whether to make it reality.

This segment aired on September 27, 2021.