Advertisement

'Forever chemicals' widespread in Mass. surface and ground water, says new report

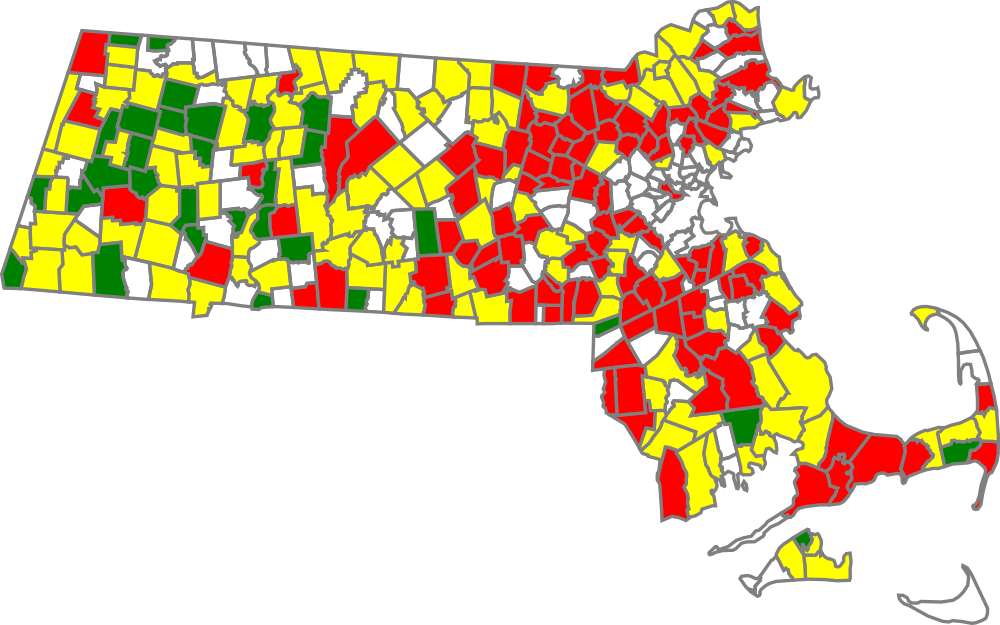

A new analysis of Massachusetts public water systems by the Sierra Club finds that 70% of communities have detectable levels of the six most dangerous PFAS chemicals in their ground and surface waters. When looking at a wider range of PFAS chemicals, 91% of communities have detectable amounts in at least one of their drinking water sources.

The data does not reflect treated drinking water, and so does not indicate a direct threat to public health.

"This isn't a study of drinking water exposure to people, so much as a study that's looking at the underlying contamination from which we're having to source our drinking water," says Clint Richmond, the Toxics Policy Lead at the Massachusetts Sierra Club. "What's shocking is that these drinking water sources are mostly underground — some are surface, but mostly this is water that's deep underground."

The new analysis of state data follows reports of PFAS contamination in Cape Cod ponds and many Massachusetts rivers, pointing to widespread contamination throughout state lakes, ponds, rivers and aquifers used as sources for drinking water.

There are thousands of PFAS chemicals, which have been used in consumer products and firefighting foam for decades, and can leach into surface and ground water from places like landfills, factories and military bases.

PFAS compounds do not break down easily and are often called "forever chemicals." Studies have linked PFAS exposure to elevated cholesterol, thyroid disease, damage to the liver and kidneys, effects on fertility and low birth weight.

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection requires testing for 18 PFAS chemicals in all public drinking water systems, and has set a combined limit for the six most concerning PFAS chemicals at 20 parts per trillion. The state is well ahead of the federal government, which has only recently moved to regulate PFAS.

The department did not respond to a request for comment on the analysis.

"Everybody's focused on the six because those are the ones that have been identified as having immediate public health hazards. But as we know, this is a large class of related chemicals," says Richmond. "We recommend that we develop standards for all of these chemicals."

Richmond says the state should also pass laws like those enacted in Maine that restrict the use of PFAS in the state.

"We want to turn off the tap of these chemicals before every community becomes contaminated," he says.