Advertisement

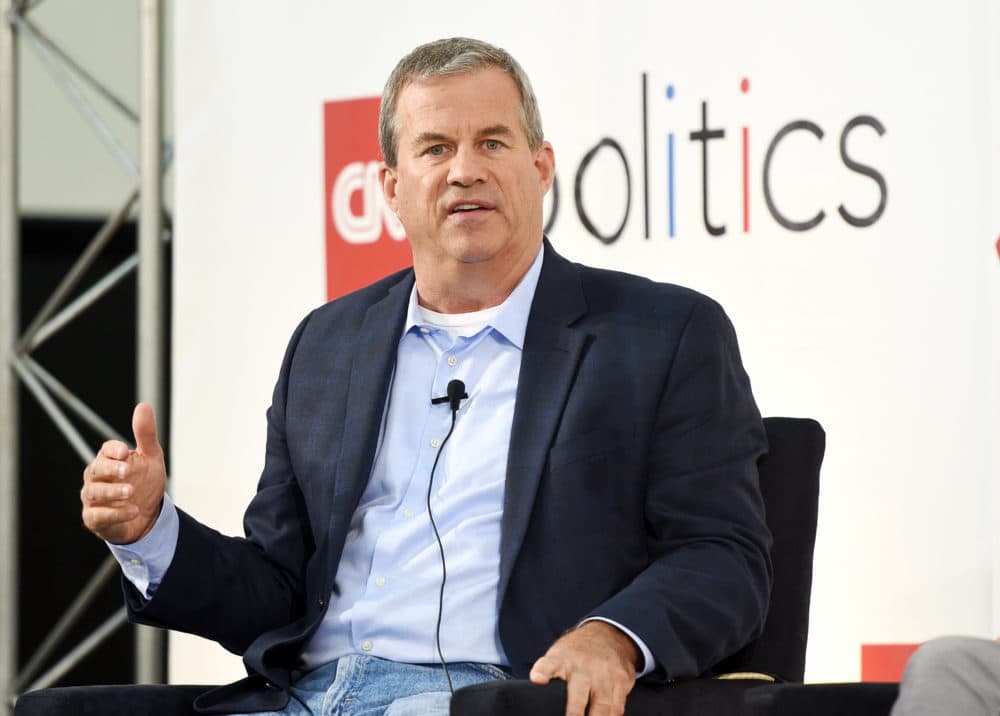

Journalist Quinones' book links new meth with growth of cities' tent encampments

Resume

It's often called the "fourth wave" of the country's addiction crisis: first pain pills, then heroin, then fentanyl, and now, stimulants such as methamphetamine.

Although there are no exact numbers, Massachusetts health care providers and law enforcement say meth use here is on the rise. The state Legislature has created a commission to further research the drug and possible treatments. It holds its first meeting next month.

In his new book, journalist and author Sam Quinones says methamphetamine use has become more complicated over the past decade, largely because of the way it's manufactured and what the drug does to the brain.

In the book "The Least of Us: True Tales of America in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth," Quiniones says this particular meth is fueling the growth of homeless tent encampments around the country, like the one in Boston at Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard.

He spoke with WBUR's Morning Edition about his reporting. Below are interview highlights, lightly edited for clarity.

Interview Highlights

Would you explain what you found out in your reporting about the methamphetamine on the streets now and how it has changed?

Methamphetamine for many years in Mexico was industrialized by the trafficking world. They made it in large quantities of meth with a chemical known as ephedrine. It's a decongestant found on Sudafed pills and that kind of thing.

Then, the Mexican government decided to effectively outlaw ephedrine, and this meant that the trafficking world had to switch the methods in which they made meth. There is another method. It's much messier. It takes a lot more work and requires far more chemicals, and it stinks. It does, however, have one benefit that the ephedrine method doesn't have, and that is that you can make it with a variety of combinations of different, very commonly available industrial chemicals. This allowed them to begin to make methamphetamine in quantities that the ephedrine method never allowed to be made. It's just stunning.

Startling quantities of methamphetamine now are being churned out of Mexico — far more than with ephedrine before. Meth never really made it out of the western United States in any sustained quantities. But really since about 2012 or '13 it has marched across the country.

This meth they can make with all kinds of different, commonly available chemicals, and they have access to two shipping ports in Mexico through which they get those chemicals. So they can make it in these stunning quantities and drop the price — which is down by about 80%.

In the book you talk about a retired Albuquerque police narcotics supervisor who trains police departments about small meth labs. He told you that meth really hadn't hit New England until 2018 or 2019. What do you think that means in terms of where we in Massachusetts are with the prevalence of meth?

An educated guess would be that it is going to grow, because once markets are discovered, they're rarely neglected, particularly if you have the supply. I think in New England, they're finding a virgin market, because you've never really had much meth up there to speak of until the last two or three years.

You write about meeting a man named Eric and what he told you about what this type of meth did to his mental state and how he went into mental decline, really. What did you learn from him and others about the mental effects of the drug?

I was very lucky to meet Eric. He was the first one who clued me in to what what exactly is happening mentally to users as a result of using this new math coming out of Mexico. He described a very serious paranoia; that all of a sudden, he was certain his girlfriend had a man in the house, and he began violently stabbing the walls and the mattress looking for this man. Eventually, there were hallucinations.

It's a cerebral decomposition that is rapid, and it never really leaves even after you stop using. It took him a long time, and he still wonders if he's ever really back to normal.

According to my reporting ... it's happening across the country. You see these symptoms showing up in Albuquerque, in rural Indiana and West Virginia. In places, in fact, where they never had homelessness before. And now they have homelessness. They have people wandering the streets completely unbalanced. You have the tent encampments popping up. Tents are perfect lodgings for people who are suffering from this kind of meth-induced paranoia and hallucination because the entire world seems a threat and now out to get you. Certainly, you can't live in an apartment or a house, and you really cannot live in a homeless shelter, because it's very scary there. The tent is like this pod of isolation.

We've been seeing a lot of these tent encampments, not just in Los Angeles. Of course, you've got them in the 'Mass. and Cass' area of Boston. None of this used to happen with the meth that the Mexicans used to make back 10 or so years ago. There was not this rapid onset of schizophrenia, rapid onset of hallucinations.

Is there research that could back that up or looks at the effects of this newer meth as opposed to ephedrine meth ?

There is no scientific research on this at all. None. What I am giving you is basic street reporting, shoe-leather reporting, talking to a lot of people across the country who give me the same story over and over. And since publishing this, I've heard from many other folks — many health professionals who work in emergency rooms or mental health clinics. And they can't tell really if the person in front of them is mentally ill or has this meth-induced psychosis. I'm hoping that my reporting, which breaks this story, will maybe push scientists to say, 'Hey, let's take a look at this.'

You mentioned the 'Mass. and Cass' area of Boston and tent encampments. I've spoken with some providers about what they think the prevalence of meth use is among those who live in this encampment. They estimate that about 20% of people in the encampment say that meth is their drug of choice. There are not a lot of hard numbers in Massachusetts, but there are reports that acute psychosis is an issue. Why do you think more people are using this drug?

I would say that the supply and the price are two major reasons why people use it. And a lot of folks on the street or folks near the street are now trying to avoid fentanyl. Meth won't kill you the way fentanyl will. It becomes a drug that you use to remove yourself from the fact that you are homeless.

I was talking with an emergency room psychiatrist in Columbus, and she said most of these folks are homeless because of meth, but meth also removes them sufficiently from reality. So they're not aware that they're homeless. It takes them to another world. It really does damage to the memory, too, so they can't kind of remember what's gone on.

We're also in an era of polypharmacy, as well. But I would say that meth removes people from really any serious possibility of wanting to get treatment, and there is no medical treatment for methamphetamine use. You just simply have to be away from the dope.

This is all about supply really. This is simply what benefits traffickers, what helps them, what gets them more profit, what lowers their risk. That's the reason we're seeing this stuff. So it's something that I think will be with us for quite some time, because it really benefits traffickers.

But there's demand as well. Our country seems to have an insatiable demand for drugs.

Yes, it does, but it doesn't have an insatiable demand for the drugs that are now on the street. We created an enormous new body of opioid addicted consumers through the supply provided at one time by doctors. And promotion, of course, by pharma companies. We did not have this massive market before that. The trafficking world is saying, 'How can we make money off of this? Well, we'll market this new heroin substitute and that will take people up to much higher levels of tolerance. And it will be very difficult to get off the stuff at that point.'

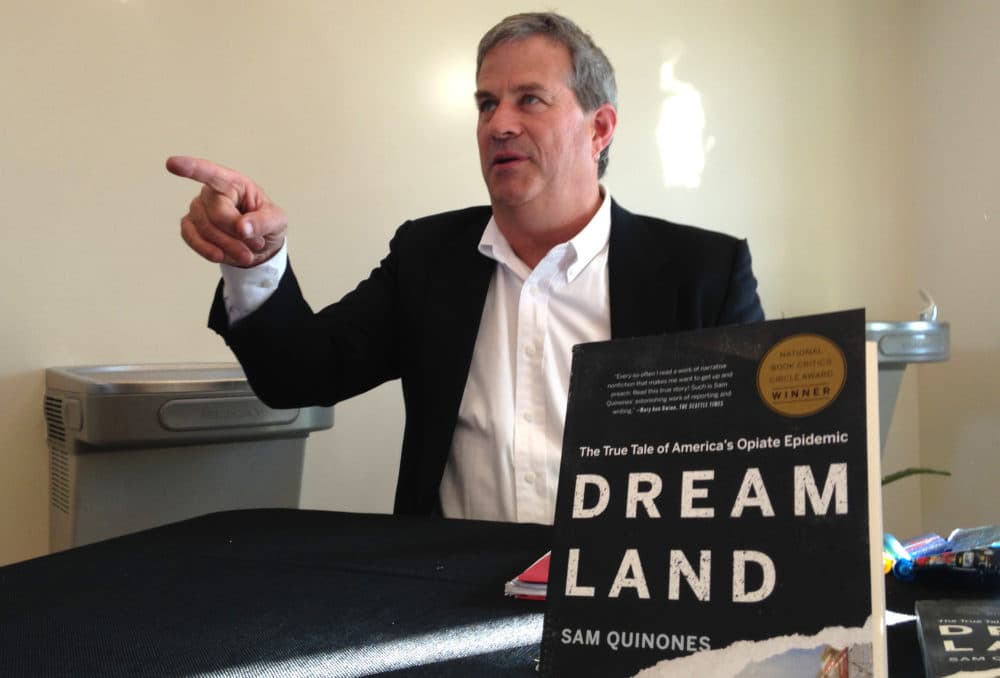

This book builds on your last book, "Dreamland," which was about the opioid epidemic. But you talk about opioids in this book, too, and Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey's lawsuit against members of the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma. How significant was Healey's suit ?

I think the lawsuit brought by the Massachusetts attorney general was very, very important. It was the first time the Sacklers were sued by name, pointing out particularly those who served on Purdue's board. And once you start getting into that, once you get into people — actual people — I think it begins to be the deterrent that lawsuits ought to be.

When I wrote "Dreamland," there was no awareness of this problem at all. In fact, there were three lawsuits when I turned my manuscript in. Within a couple, maybe three years, there were hundreds — eventually reaching 2,600, maybe even 3,000. This demonstrates the growing awareness of the problem, and that people were finally willing to talk about what was happening. A lot of this is because of people coming out and not hiding that their child or loved one is addicted.

You've written that it's now cliche to say, 'We can't arrest our way out of this.' But you also say we can't treat our way out of this either. So what is the way out? Because it sounds so grim.

No, it's not grim. It's natural to think, 'Oh my God, this is beyond us.' But that's because I think we have turned our backs on the most potent force that human beings know, and that has kept us alive and allowed us to survive as a species for millions of years. And that is the power of community. We have never turned our backs on that. We always understood as a species how important all that was until, say, the last 30, 40 years in America, where all of a sudden it was like, 'What do we need to be around other people for?' And we left ourselves completely shredded.

Everybody can be part of this. And that is what these epidemics — this [COVID] pandemic and the opioid scourge — are teaching us: that we are better together, that we are only as strong as the most vulnerable. We're only as strong as the least of us.

This segment aired on November 29, 2021.