Advertisement

How this COVID surge compares to last winter, and when it could peak in Massachusetts

Skyrocketing. Lightning speed. Engulfed in the omicron wave. Case counts look like a hockey stick, shooting upward.

There’s no shortage of ways to describe the dramatic rise in COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts.

The current wave is dwarfing last winter’s surge.

Hospitalizations are also up sharply, putting a strain on hospitals, although evidence suggests that omicron causes less severe illness, especially for vaccinated and boosted people, than previous variants of COVID-19. Thankfully, deaths have not risen to past levels.

So, where is this omicron wave heading? When will it crest? How bad will it be?

WBUR spoke with epidemiologists, forecasters and medical professionals to get some answers.

Is there light at the end of the omicron tunnel?

Experts say the peak is projected to come before the end of January.

Samuel Scarpino, the managing director of pathogen surveillance at the Rockefeller Foundation, said the best modeling suggests that the U.S. wave will peak in about two to four weeks, and then case counts will start dropping.

Cities with a lot of omicron right now may peak sooner than the rest of the country.

“There’s some evidence that cases may be already starting to peak in Washington, D.C. So, for a place like Boston or New York City, it could be one to three weeks instead of two to four weeks before we see the peak,” Scarpino said, pointing to forecasts produced by the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub.

In Boston, he said there are indications that people have been moving around less. This could reflect winter vacations, or people staying home because they are sick. But Scarpino thinks it might also suggest that people who can hunker down are doing that — and this could help slow the spread.

Advertisement

In South Africa, omicron cases rose incredibly rapidly and then fell very rapidly. Can we expect the same in Massachusetts?

Bruce Walker, director of the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT and Harvard, said we can’t be certain. Walker, who also co-leads the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness, said the population in South Africa looks quite different than the commonwealth or the U.S.

“It’s a much younger population in South Africa,” Walker said. “The feeling is that what’s being observed in England is a population that’s closer to the population here in terms of age and comorbidities.”

The omicron wave in the U.S. is also distinct from South Africa because of its timing. It came during the holiday period when there was extensive travel and gatherings. It also came on top of a resurgeant wave of cases driven by the delta variant.

“The timing of omicron in the United States was really challenging,” said Jacob Lemieux, an infectious disease specialist at MGH. He expects the peak will be higher in the U.S. — and it may take longer to recede — compared with South Africa.

How reliable are COVID forecasts?

Some of the most reliable predictions come from what’s called an “ensemble” forecast, which combines many models into one forecast. The resulting prediction, Scarpino said, is quite good.

“If we're looking at forecasts that are up to about a month out, these models are highly accurate, and they have performed incredibly well over the course of the pandemic,” he said. “Now, once you start to get out past five or six weeks, that's where a lot more uncertainty comes in.”

The full impact of this wave may not be reflected in daily COVID reports from the state. How is this possible?

The case counts coming from the state are very high. But there are signs that the coronavirus is even more widespread in Massachusetts than those numbers suggest.

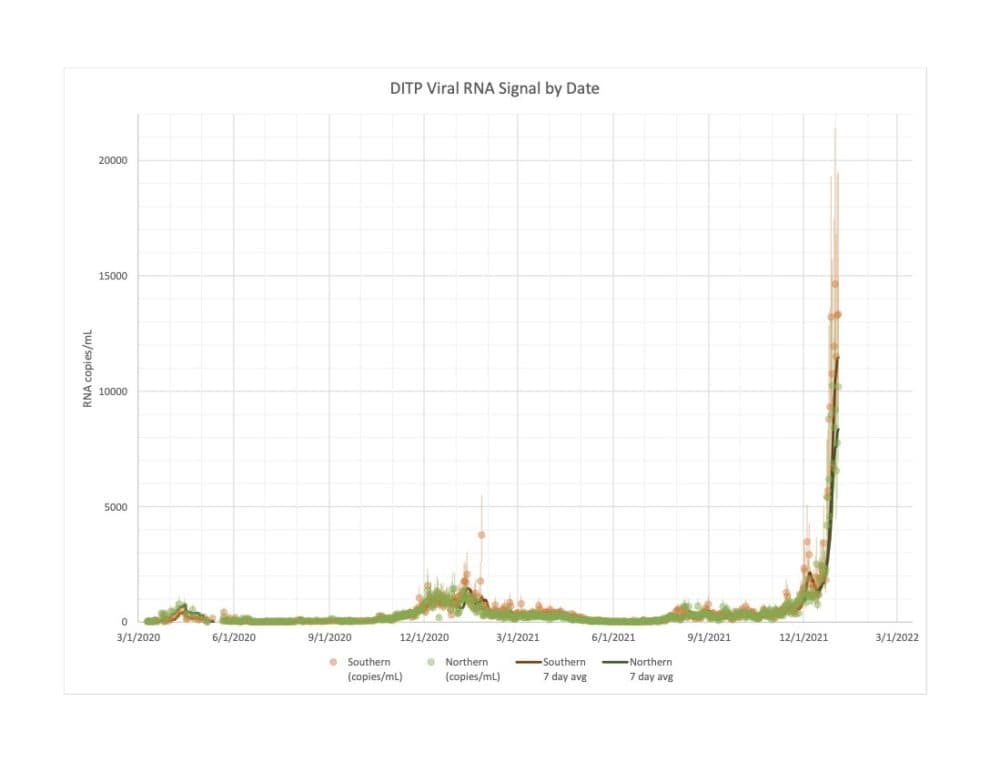

One indication comes from wastewater. Biobot Analytics measures the levels of COVID found in sewage. Data from a partnership with the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority or MWRA showed levels of the coronavirus that are many times higher than the previous peak and significantly larger than the spike seen in official case counts.

“The level is absolutely terrifying,” said Jeremy Luban, professor of molecular medicine and molecular pharmacology at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. “There's just huge amounts of virus in the community that's circulating, and it's not necessarily reflected in the test positivity.”

There are likely several reasons for the discrepancy between the official case counts and the levels measured in wastewater.

For one thing, it’s not easy to get a test right now, so many people who are positive may not be getting tested. Another factor could be at-home rapid tests. They're increasingly common, and the results are often not reported to the state, so they aren’t captured in case counts.

Scott Olesen, an epidemiologist at Biobot Analytics, said it’s also likely that many people have only mild cases or are asymptomatic, so they don’t realize they have the virus.

“One of the values of wastewater monitoring is that you're getting a picture that doesn't rely on symptoms and doesn't rely on testing to any degree,” Olesen said, noting that people with omicron seem to expel the same amount of virus in their stool as people who had other COVID-19 variants.

“We do a lot of double checking. We do a lot of re-running of our lab results. It's tempting to say, ‘Oh this, this can't be happening’ because I don't want it to be happening,” Olesen said. “But there really is that much virus in the wastewater.”

How does the omicron wave look different from previous variants?

In terms of the general population, omicron spreads much more quickly, and it seems to be less severe. However, people are still being hospitalized from it and dying from it. Massachusetts hospitals have already reached the peak seen in the last surge and are bracing for more COVID patients in the coming weeks.

Kyan Safavi, who does internal forecasting at MGH to help the hospital make logistical and staffing decisions, said his team's models look two weeks out and, right now, they expect hospitalizations to rise throughout that period.

However, Safavi said, in the hospital this wave looks quite different from what he's seen in the past.

“In the spring of 2020, about 38% of all of our COVID hospitalizations were on the ventilator during the peak of that wave. In wave two, it was about 20%. And so far in December and through today, we’re closer to 13%,” he said.

MGH has also found that a much higher proportion of its COVID patients — as high as 45% — are admitted for something else and just happen to test positive for the coronavirus. That means hopefully fewer COVID patients will need ICU beds.

This segment aired on January 6, 2022.