Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

What's different — and what's the same — with omicron in hospitals

Virtually all COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts are now resulting from the omicron variant. It took over in hospitals in late December, according to an analysis from Cambridge Health Alliance. It’s still early in the omicron surge, but it’s coming on fast, so we asked several doctors and nurses what they are seeing with omicron, to get a sense of how patients are faring and how this surge compares to prior waves of COVID.

Let’s start with a question that can be confusing. We’re hearing that omicron triggers a milder case of COVID in most people as compared to prior variants. So why are hospitals so overwhelmed?

The explanation is in the math and how easily omicron spreads.

“Many, many, many more people are getting infected. Although a smaller percentage of those people are getting hospitalized or dying, it still ends up being a very significant amount of people because it’s so contagious,” says Dr. Huan Ngo, chief medical officer at Signature Healthcare, which includes Brockton Hospital.

So significant, says Ngo, that Signature Brockton has roughly the same number of patients with COVID this week as it did at the height of the pandemic in 2020.

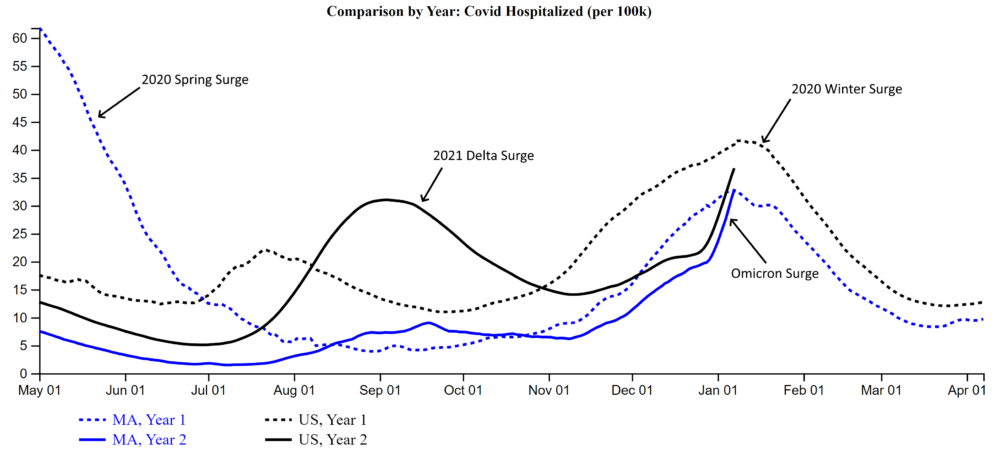

Statewide, hospitalizations have already reached the peak of last winter’s surge, according to data analyzed by Dr. Tom Seufert, director of emergency informatics at Cambridge Health Alliance.

"The pace at which cases have risen with omicron has been unprecedented — anywhere in the world, and with any prior surge," Seufert said in an email exchange.

With omicron, there may be a greater chance of patients arriving after a car accident or heart attack who happen to test positive, rather than COVID being the reason they are in the hospital. More on that below.

Omicron In The Emergency Room

Some emergency rooms are seeing record numbers of patients this week. Many just want a coronavirus test because tests are so hard to find. Some ERs have started limiting tests to people with symptoms.

Dr. Omer Moin, chief of emergency medicine at Lawrence General Hospital, says the spike in demand for testing may be because omicron seems to produce symptoms quickly, within a day or two, in addition to the fact that it is more contagious than other variants.

Many people who don’t need hospital-level care go home right from ER waiting areas because beds and hallways inside emergency rooms are full, says Dr. Ali Raja, executive vice chair of emergency medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“We need mass testing sites, organized by the state or health care systems, with same day results,” says Raja. “There are too many people who can’t find tests.”

Advertisement

Fewer Patients With Omicron Seem To Be Losing Their Sense Of Taste Or Smell

Otherwise, patients have the same complaints doctors have been hearing for two years now: cough, fatigue, sore throat, and congestion.

Omicron On Hospital Wards And In Intensive Care Units

It’s not clear yet if patients who get admitted to the hospital with the omicron variant have a less severe version of the disease or are less likely to battle longer-lasting symptoms known as long COVID. A study conducted at Houston Methodist Hospital shows patients infected with omicron spent about half as much time on a ward as compared to patients infected with the delta variant.

Justin Precourt, chief nursing officer at UMass Memorial Medical Center, says he doesn’t have numbers, but that’s consistent with what he’s seeing. He suggests two reasons. First, hospitalized patients with omicron don’t seem to have as much lung damage, so they don’t need as much oxygen support. And second, the current COVID patients in his hospital and some others appear to be younger and less likely to have chronic ailments — like high blood pressure, obesity or diabetes — that seem to complicate COVID.

“Those two things are the keys to what’s driving a lot of what we are seeing,” says Precourt.

“Many, many, many more people are getting infected. Although a smaller percentage of those people are getting hospitalized or dying, it still ends up being a very significant amount of people because it’s so contagious.”

Dr. Huan Ngo, Signature Healthcare

Less need for oxygen support means fewer omicron patients are transferred to an intensive care unit. The percentage of COVID patients needing intensive care has dropped from nearly 50% at UMass Memorial during the first wave in 2020 to between 20% and 25% now. That’s true at many hospitals as medical teams have learned more about treating COVID.

At MGH, 38% of COVID patients needed a ventilator during the first COVID surge as compared to just 6.3% now. But there’s no change in the intensity of prolonged care these patients need.

“Patients who are in the ICU remain just as sick as the patients who’ve been in the ICU during prior waves, and those are almost exclusively unvaccinated people,” says Dr. Kathryn Hibbert, the interim chief of pulmonary and critical care at MGH.

Even though omicron is not a key reason, ICUs at MGH and across much of the state are full. Hibbert says MGH is turning away patients she’d like to see the hospital take, but there just aren’t enough staff to manage the patients.

Omicron, a particularly contagious COVID variant, is sweeping through hospital employees too, adding to the staffing shortages that have already reduced hospital capacity.

Two Kinds Of Omicron Patients

At some hospitals in Massachusetts there’s a growing distinction with omicron: Patients whose primary reason for admission is COVID, and patients who arrive not realizing they are infected.

At Lawrence General, fewer than 10% of patients who’ve tested positive are what’s known as “incidental cases.” But at MGH, 42% of the more than 219 patients who had COVID on January 6, 2022, came to the hospitals for something else: an injury, chest pain or a foot ulcer related to diabetes, for example.

Whatever the reason for their trip to the hospital, these patients create challenges, says Dr. Erica Shenoy, the associate chief of infection control at MGH. They must stay in private rooms with doors that close. Everyone who interacts with them dons a full suit of personal protective equipment. Their care can be more time consuming.

While COVID is not their primary diagnosis, clinicians are debating whether COVID played a role for patients hospitalized with a chronic condition. Someone with omicron might not realize they have a coronavirus, but still be sick enough that they forget to take their medication, eat well, exercise or drink water. Or perhaps COVID makes managing the biology of their disease more difficult.

“What we don’t fully understand is whether it’s COVID that put them in an unstable position or if the symptoms made them unable to care for themselves,” says Raja, “or if it could be both.”

And whether COVID is the primary reason for hospitalization, discharging patients who’ve tested positive is becoming increasingly difficult during this omicron surge.

Some skilled nursing facilities have so many staff out they can’t accept patients who need care while recovering. Some addiction treatment programs and psychiatric hospitals are also not taking new admissions. Omicron is clogging hospital entrances and exits.

With Omicron, The Impact Is Still Not Fair

Health disparities that have been present for low-income people of color throughout the pandemic remain with omicron. This variant does not appear as mild in some communities with higher infection and lower vaccination rates.

The percentage of patients needing intensive care at Signature Brockton Hospital, which serves a significant Haitian and Cape Verdean community, has been almost as high during this surge as it was at the beginning of the pandemic, 66%. And Ngo, the medical director, says virtually all COVID patients there “are sick enough to need respiratory support and oxygen.”

At Lawrence General Hospital, which serves a large Latino community, the number of patients hospitalized for COVID has almost tripled in the past three weeks, and demand for ICU beds is rising. Moin, who runs the emergency room, says patients are still struggling with the same issues that have made them more vulnerable to COVID all along: high rates of chronic disease, less access to primary care and COVID treatments, language barriers, the need to work outside the home, crowded housing and other social inequities.

Ngo says he is pleased to see fewer deaths, so far, compared to other surges.

“The spike in deaths is not as high as we would expect with the spike in the overall number of COVID hospitalizations and cases,” he says.