Advertisement

Commentary

Francis Ford Coppola's 'The Conversation' is a character study disguised as a mystery

Eighty-two years old and reportedly ready to start shooting his decades-delayed dream project “Megalopolis” in the fall – a movie I’ve been reading rumors about for as long as I’ve been reading rumors about movies — Francis Ford Coppola has been in legacy mode as of late. Over the past few years, the maestro has released revised edits of “Apocalypse Now,” “The Outsiders,” “The Cotton Club” and “The Godfather Part III.” (The latter two are indeed significant improvements, but with the others, you should stick with the originals.) Yet, no such tinkering was necessary when it comes to “The Conversation,” the chilling 1974 masterpiece Coppola has often cited as his favorite of all his films. A digital restoration with a new surround sound mix supervised by the film’s editor and sound designer Walter Murch was originally scheduled to open here in Boston back in April of 2020, but we all know what happened then. Now at long last, “The Conversation” is returning for a one-week engagement at the Somerville Theatre beginning Feb. 4.

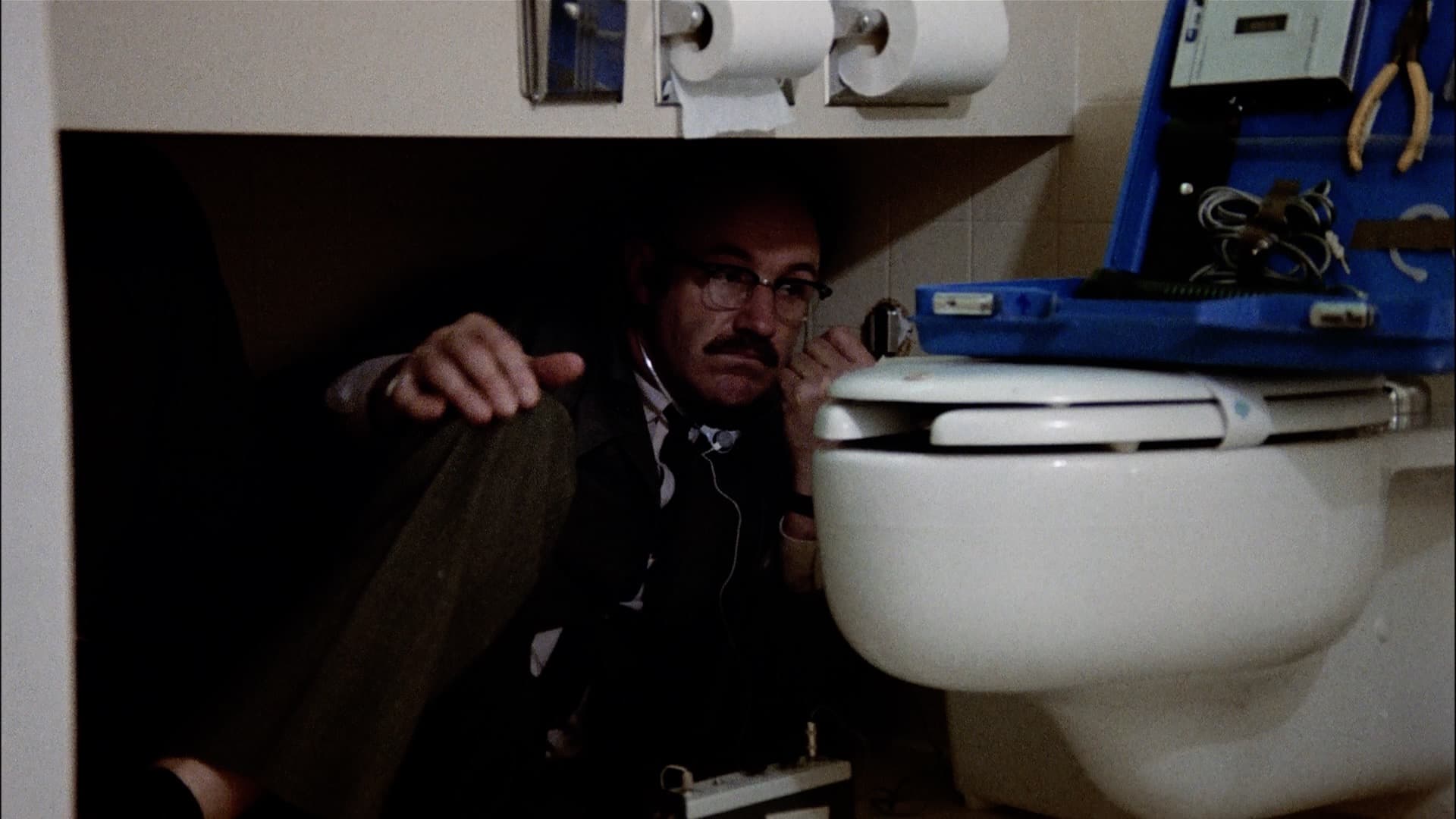

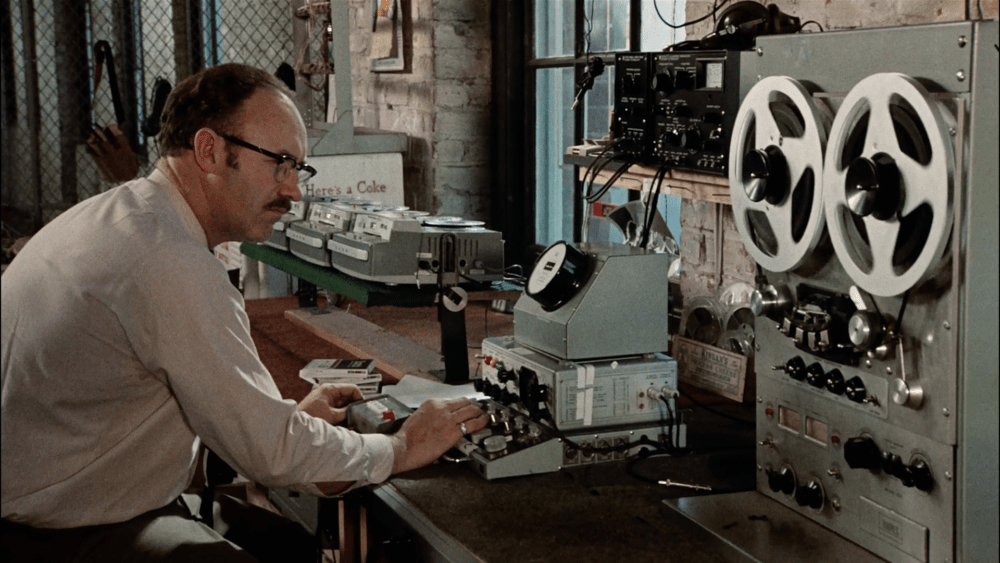

Sure, I suppose you could stream it. But you know how some movies need to be seen on a big screen? “The Conversation” needs to be heard in an auditorium on the kind of equipment you don’t have at home. It’s an intricately constructed aural experience about the act of listening, and how sometimes our perceptions of sounds are shaped by what we want to hear. Gene Hackman stars as Harry Caul, a buttoned-up wiretap expert known as “the best bugger in the business,” running private surveillance jobs on cheating spouses and the like. He’s recruited by a nameless corporation to record a secretive young couple (Fredric Forrest and Cindy Williams) making furtive plans amid bustling crowds and a jazz band in San Francisco’s Union Square.

The film’s opening is a dazzling tour de force, during which snatches of their dialogue are captured by different devices – including shotgun mics wielded like snipers on rooftops catching the lovers’ lips in the crosshairs – to later be assembled and refined by Harry back at his workshop. The cryptic conversation sounds different every time we hear it, alternating on a moment-to-moment basis between banal small talk and something more menacing. The fey functionary who hired him (played by an impossibly young and sinister Harrison Ford) seems to want this tape awfully badly, and even though Harry’s not supposed to ask any questions in his line of work, he’s starting to have a few. He’s also pretty sure he won’t like the answers.

“The Conversation” is a character study disguised as a mystery, more interested in paranoid Harry’s psychological unraveling than in any conspiracy that’s actually afoot. We know Hackman as such a feral, roughhousing screen presence it’s a shock to see him withdrawn so deeply into the character’s guilt-ridden neurosis. He’s an ineffectual introvert in bad glasses and cheap clothes, so emotionally cut off from the world he can barely communicate. Harry offers only admonishments and insults to his long-suffering assistant Stan (the great John Cazale) and keeps a careful emotional distance from a mistress to whom he won’t even give his phone number, touchingly played by Teri Garr. (It’s kind of a mean joke making a movie called “The Conversation” about somebody incapable of having one.) Hackman has called the performance his finest work, though personally, I’d give a slight edge to his turn in Arthur Penn’s “Night Moves” the following year, in which he played a detective who, like Harry Caul, only belatedly comes to understand how much he doesn’t know.

Written by Coppola in 1969 and rejected by every studio in town, “The Conversation” was eventually produced as a low-budget indulgence by Paramount Pictures, who wanted to keep their newly minted superstar happy and hopefully cajole him into making “The Godfather Part II.” Coppola had such a miserable time on the first film that he desperately didn’t want to direct the sequel, suggesting to the studio that the project would be perfect for an up-and-coming kid named Martin Scorsese. He eventually tried to get out of it by making an astronomical salary demand he was sure would get him laughed out of the room. They accepted. (Yes, it was an offer he couldn’t refuse.) Ironically, for a director so adept at sweeping, popular epics, “The Conversation” was the kind of interior, personal art film Coppola had originally envisioned himself making and held closest to his heart. Though even on such a small scale the process was anything but smooth.

Coppola clashed with cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who was eventually replaced by Bill Butler. (All that remains of Wexler’s work is the bravura opening sequence.) Hackman was a mercurial star under the best of circumstances and admittedly had a horrible time getting under Harry’s skin. (There’s an unintentionally hilarious behind-the-scenes promotional short from 1974 included on the old Paramount DVD, in which you can cut the tension between the actor and director with a knife. Though it’s worth noting that 24 years later Hackman returned to the role, playing a jocular homage to Harry Caul in Tony Scott’s “Enemy of the State.”) Running out of time and money, Coppola pulled the plug four days ahead of schedule with something like a fifth of the script still to be shot, leaving the footage for editor Murch to sort through while he went off to make “The Godfather Part II.”

Like the making of a lot of great films, the editing of “The Conversation” was a series of happy accidents and necessity breeding invention. A botched take of the original ending was repurposed as a dream sequence midway through the film, and Murch’s elliptical approach to the mystery’s resolution is a hundred times more haunting than any straightforward exposition could ever be. (If you squint hard enough during his revelatory, multi-perspective montages during the film’s final act you can see Steven Soderbergh’s career being born.) The radical restructuring required only a single pickup shot when the director returned to the project, one pulled off in the corner of a set on the Paramount lot where pals Jack Nicholson and Roman Polanski were shooting “Chinatown.”

Advertisement

Coppola has said he got the idea for Harry’s dilemma after hearing about film editors who fall in love with leading ladies they’ve never met, smitten by spending all day with their footage. Hearing and re-hearing this conversation over and over, both we and Harry make all sorts of assumptions about these two strangers, our minds forcing the puzzle pieces to fit where they don’t belong, with tragic results. Rewatching the film it’s impossible not to be bowled over by all the visual analogues Coppola comes up with for the character’s isolation, constantly filming him behind glass or in a tacky, transparent plastic raincoat that’s easily one of the ugliest costumes in movie history. His workshop is in a massive, empty industrial floorspace in which Harry occupies a small corner, locked in a cage of his own design. The gradual demolition of the apartment building across the street from Harry’s is both an extension of his mental breakdown and the tearing down of walls in a movie where privacy only exists to be invaded.

“The Conversation” runs at the Somerville Theatre from Friday, Feb. 4 through Thursday, Feb. 10.