Advertisement

Q&A: What Tulane professor Diego Rose has learned about climate change and the American diet

Diego Rose was studying food security in New Orleans when he got invited to a three-day workshop on “ecosystem services” — the various things that nature does for humans, like when trees suck up water and give up oxygen. “I didn't even know what ecosystem services were,” says Rose, a professor of food and nutrition policy at Tulane University. “I had never thought much about this stuff.”

The workshop changed the direction of Rose’s career. He teamed up with Martin Heller at the University of Michigan and began studying how Americans can make their diets more climate-friendly. He uses national data to look at what Americans eat, and the environmental impacts of certain foods. His most recent research, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2022, found that swapping one serving of beef for chicken each day would lower a person’s dietary carbon footprint by 48%.

This Q&A contains excerpts from two interviews, condensed and edited for clarity.

Your research focuses on individual people and actual diets — where do you get data like that?

We’re working with national data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. They ask individuals to recall everything they ate in the last 24 hours. It's just a snapshot — it's a random day in the in the eating life of a sample of Americans. And they have repeated this throughout the year and over a number of years.

So, there are pepperoni pizzas and lasagna and all kinds of stuff that people eat, and those "as-consumed" foods are pretty complex. If you think about a pepperoni pizza, there are tomatoes and wheat and dairy and pork and spices and all kinds of stuff. But the environmental impact studies — called 'life cycle assessments' — are all based on commodities. They're not based on as-consumed foods.

In our data we have 6,000 different food items that individuals eat, and there are maybe 200 to 300 commodities that people look at for life cycle assessment studies. So, there's this disconnect; how do you combine those two? It’s complicated.

So how did you do it?

In the pizza example (and this was a key turning point) we found a data set that had recipes that translated a pizza into commodities.

This had been done by the Environmental Protection Agency. They were particularly interested in being able to translate what Americans ate into commodities because they were regulating the use of pesticides. So, they wanted to be able to estimate how much pesticide exposure individuals would have through diet. The only way to do that would be to be able to translate those as-consumed foods into commodity recipes.

One of the first articles to come out of this line of research was in 2018, and the team found that about 20% of Americans’ diets account for about 45% of the environmental impacts [that come from food]. What are those people eating?

We started looking at those diets, opening them up one by one, and that's where we learned that some Americans eat a really weird combination of foods. But out of a whole set of foods, there would be one of them that would stick out as having a really big impact. And it was almost, not always, but a lot of times, beef. That’s when we started to look at it systematically.

It’s surprising that beef has such a huge environmental impact.

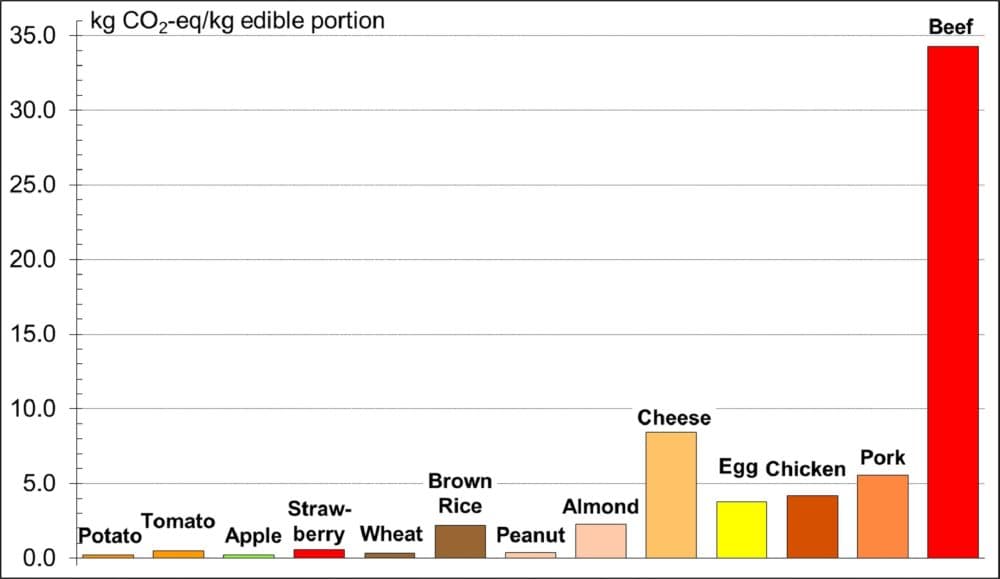

The very first chart I put together was the greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of food. I made this chart and I thought, ‘Wow, this is really dramatic.' There are all these numbers that are down here and then beef goes like, way up here. It's like you have to redesign the vertical axis to fit it; it's just another magnitude of difference.

Why does beef have such a higher carbon footprint ?

All animal products are more impactful than plant products because you have to grow the feed, and include all the impacts of those crops to feed the animals. But on top of that, with ruminant animals, there's methane from burping. They're able to digest grasses, which is a great thing if you think about it, but on the other hand, that bacterial fermentation in the gut is producing methane, which is like 30 times more impactful than carbon dioxide. So, it just really puts beef in a different ballpark.

Your most recent research looks at the environmental impact of swapping out one food for another. Tell me about your findings.

The one we started with was, 'what happens if you substitute chicken for beef?' And we're just doing it one time a day. What we found with that one single substitution: it dropped that person's dietary carbon footprint by 48%. Not their overall carbon footprint — we didn't look at their gasoline consumption or heat or anything like that — but just their dietary carbon footprint. That's pretty significant.

The idea of swapping out one item seems very manageable. Why did you frame the study that way?

There's some wonderful diets out there, but they’re complicated. Like the Mediterranean diet: OK, what does that mean and what's included? What's not included? So, we thought, instead of having this complex dietary pattern, if you could just say I'm just going to have a chicken burger instead of a beef burger, it’s easier.

It's an easy thing to recommend because you don't have to become a vegetarian to have a big impact. If you've been eating beef a lot and you can just cut back on how much you're eating, that would make a big impact.

The study also found that swapping out a serving of beef would lower somebody’s water-use impact by 30%. The food system has so many environmental impacts. Why did you focus on greenhouse gases and water use?

There's lots of different impacts from agriculture. There are only so much data that are out there. And so, we've chosen to look at what we think are the two most important things. I mean, climate wise, we have to get greenhouse gas emissions in order. That to me is the number one priority. That said, when you have a warming climate, you're going to have more droughts. And if you have more droughts, obviously you need to use less water for food production or use it more wisely. The more you drill into this stuff, the more nuanced it is.

It seems like the way beef is raised would make a big difference in its environmental impacts — why don’t your studies take that into account?

Even if you if you looked at the least impactful beef that's raised — and all beef was raised in that way — we'd still have to cut our consumption in half to be sustainable. It's just a high-impact food.

The U.S. beef industry is very efficient. The efficient feedlots are awful for animal welfare — the use of antibiotics and all the other problems that those cause — but they raise a lot of beef without as much impact per kilogram of beef. The greenhouse gas emissions of those feedlots are actually lower than the regenerative farmer in Montana who grows Bessie in the most loving of ways. There can be other benefits, of course, such as less fertilizer, less pesticides, Bessie is happier until she dies. But unfortunately, we can't eat as much beef as we do, even if we're just eating lovingly-raised Bessies.