Advertisement

This is the Massachusetts sculptor behind the Lincoln Memorial

Resume

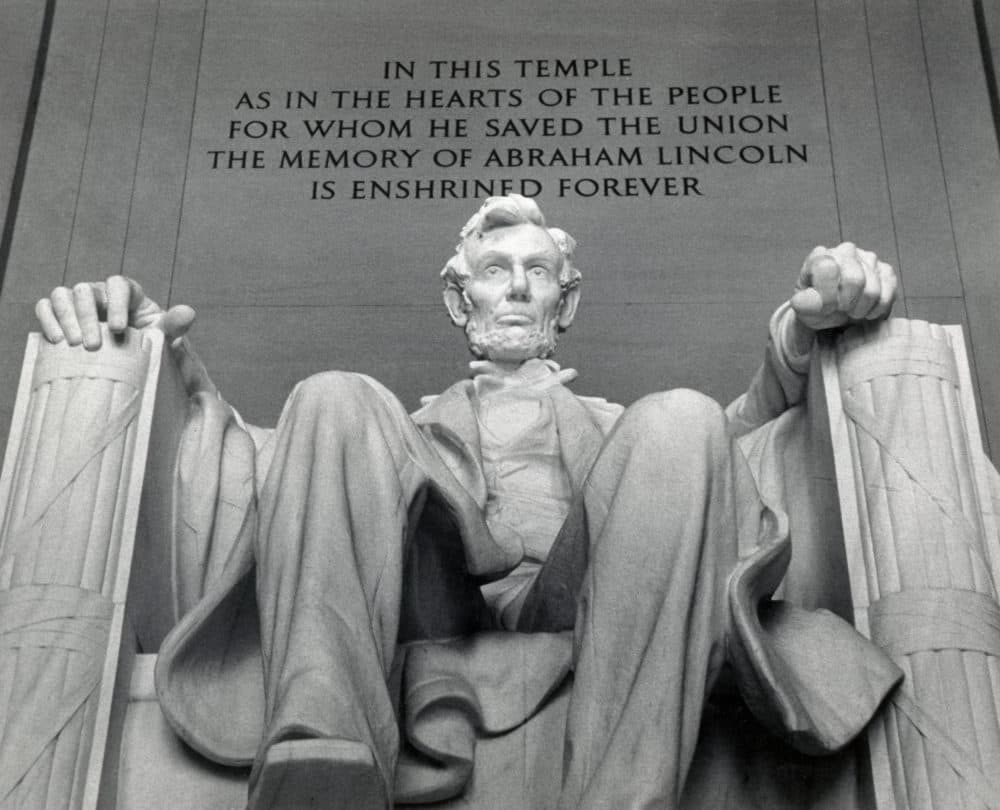

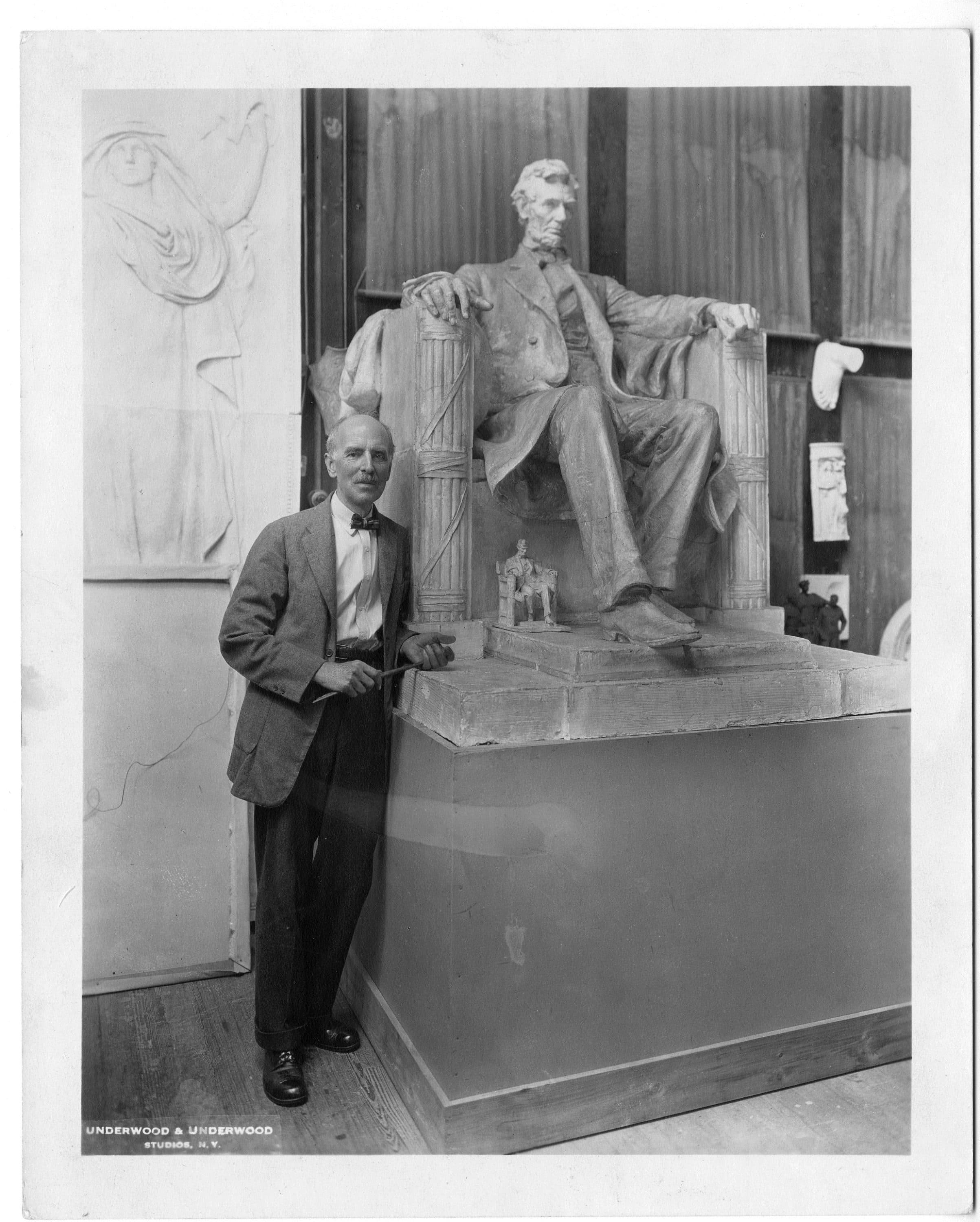

Many people will turn their attention Monday to the Lincoln Memorial as the country celebrates the 100th anniversary of its dedication in Washington, D.C. But few may remember the man behind the monument: American sculptor Daniel Chester French.

He worked on many of his greatest sculptures at Chesterwood, his summer estate and studio in Stockbridge, nestled in the Berkshires. But his ties to the Bay State go further back to his childhood spent in Concord and a stint at MIT before he dropped out to pursue his art.

Even though Lincoln takes center stage, historian Harold Holzer — an expert on both men — argues that to appreciate the Lincoln Memorial is to appreciate French and his artistic interpretation of the celebrated president.

Holzer spoke with WBUR's All Things Considered host Lisa Mullins about French and his thinking behind the Lincoln Memorial. Holzer is director of Hunter College's Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute and author of "Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French."

Highlights from this interview have been lightly edited for clarity.

Interview Highlights

On how French blended reality and imagination to portray Lincoln:

"The measurements of the eyes, the nose, the mouth — those crucial things that sculptors try to quantify and reproduce and enlarge — those are accurate. But the expression of the eyes, the tilt of the head and the hair are all French's invention and his interpretation."

On Lincoln's chair:

"I think he somewhat exaggerated the chair of state so that it could accommodate this giant of a man. In truth, most chairs were too small to hold Lincoln comfortably, and contemporaries noted that his knees were always above his waist in these chairs. That's not the Lincoln we see here. He's not scrunched up. He's almost regal. And the chair of state is every bit up to the task of accommodating him."

On the meaning behind Lincoln's closed right hand and an open left hand:

"[French] used casts of Lincoln's hands that had been made the day after his nomination to the presidency. Lincoln had clung to a broom handle for the casting. He had shaken so many hands [of well-wishers congratulating him on his nomination] the night before that his hand was swollen. The [caster] said something like, 'Oh dear, you'd better grasp something because it won't look right.' So he grasped a broom handle... Many artists just reproduced the hands as they were cast in 1860.

"Well, French would not use that. He said Abraham Lincoln would have a more open right hand, as if he was about to rise to greet someone. He would never be closed off from his people, from his constituents. I think that was a brilliant riff on those casts."

On the legend of Lincoln's hands and their alleged secret code:

"This is one of the great stories: that the right and left hands spell out, respectively, the letters 'A' and 'L' for Lincoln's initials. And they say French intended that to be the case, having previously worked on the statue of Thomas Gallaudet, the founder of the school for the hearing impaired in Washington. But there's no evidence — at least I found no evidence that he intended a subliminal message.

"French did put little messages in other statutes, you know, a little owl in the alma mater at Columbia University. So if students stood near the owl, they would make the dean's list. There's another element in another college statue, and supposedly if lovers walk by they would get married. But for that we have substantive information. But not the 'A-L.' It's just sort of an accident."

On representing national vs. racial union:

"The Lincoln Memorial was conceived as a tribute to the reunification of North and South, but it ignored the existing problems and the continuing separation of Black and white Americans. The dedication ceremony itself was brutally segregated. The only Black speaker was censored so that he could not say, as he had written, that unless the country lived up to Lincoln's promise of equality, the memorial itself would be a hypocrisy.

"And that's where matters stood until 1939 — 17 years later — when [First Lady] Eleanor Roosevelt arranged for the Black opera star Marian Anderson to sing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on a rainy Easter Sunday. Her extraordinary concert, which one can still hear on YouTube, just riveted the nation. It was broadcast on radio, 75,000 people were outdoors to hear it. And suddenly the Lincoln Memorial changed into a platform for the aspiration for racial equality.

"And, of course, most famously, Martin Luther King Jr. gave the 'I Have a Dream' speech from what he called 'the shadow' of this great sculpture by Daniel Chester French."

On his other sculptures:

"He did the great sculpture of General Hooker outside the State House; the O'Reilly Memorial on Boylston Street in Boston; a wonderful memorial to a fellow sculptor named Martin Milmore called the 'Angel of Death,' at the Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain. And maybe the most famous of his New England works is John Harvard, which is now in the Harvard Yard.

"I shouldn't leave out, because it may be his most iconic work outside of the Lincoln Memorial, when he was in his mid-twenties he got the commission to do The Minute Man for the Bridge of Concord. And that great work is still the symbol of American savings bonds and the armed forces and such. This citizen soldier hearing the sound of the British coming and defending the Old North Bridge — it's quite a great work for a young man who had never done a statue at that point."

This segment aired on May 27, 2022.