Advertisement

Water quality in Boston’s rivers was mostly good in 2021. But sewage and climate change threats remain

School may be out for the summer, but it’s report card time for Boston’s three big rivers: the Charles, Mystic and Neponset.

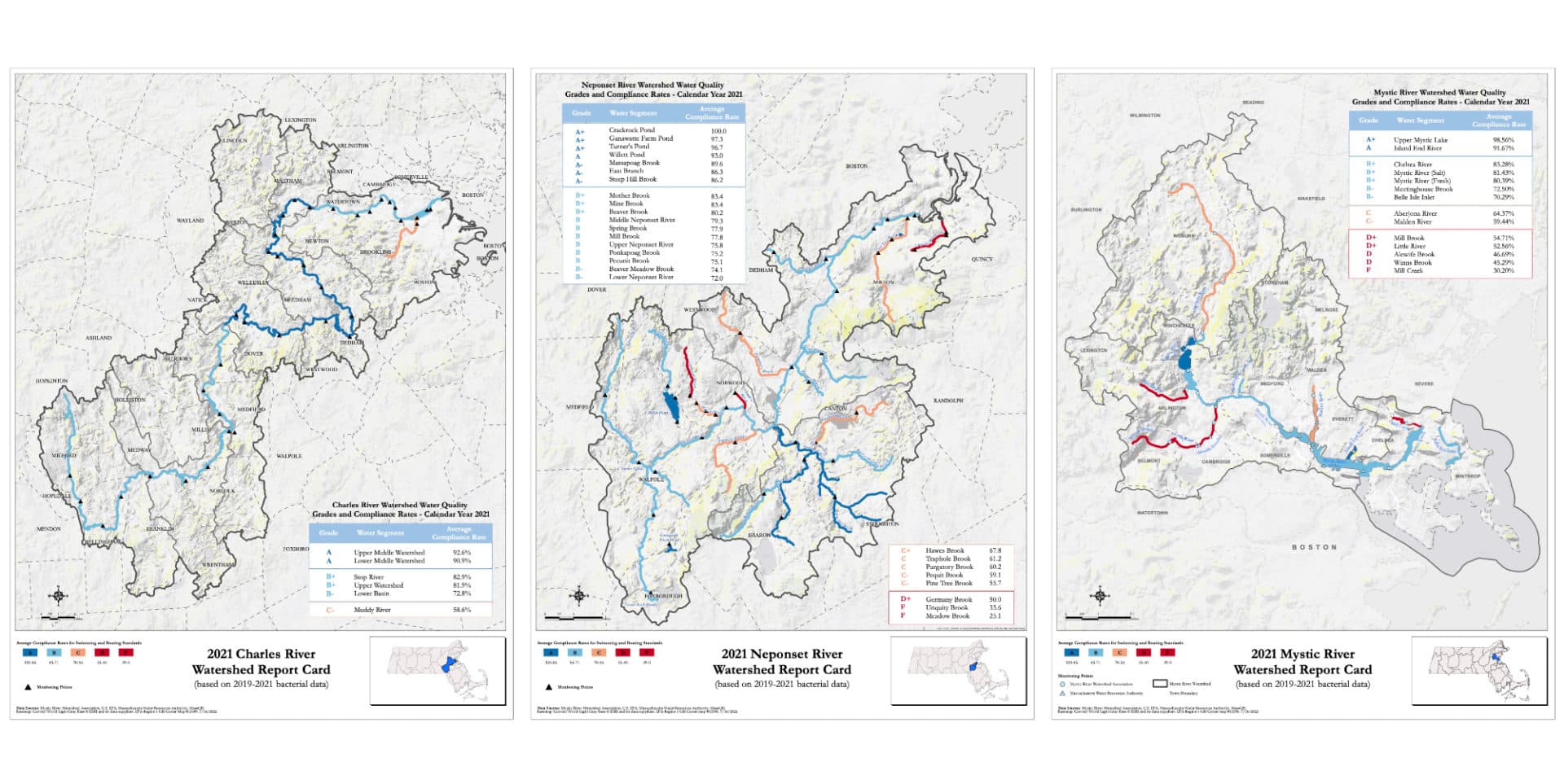

Every summer, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issues a letter grade to segments of these rivers and their tributaries so the public can track improvements in water quality. The grades are based on E. Coli concentrations, although in the case of the Charles River, the number of combined sewer overflow events and presence of toxic cyanobacteria are also factored in.

Like the previous year, most segments of the three rivers got As and Bs for 2021, but all had problematic areas.

Several parts of the Mystic and Neponset Rivers received Cs, Ds and even an F or two. These low grades were caused primarily by stormwater runoff that carried lawn fertilizer, road salt, dog feces, gasoline and other pollutants into the waterways. According to the Neponset River Watershed Association, water quality in the Neponset declines, on average, about 22% during heavy rainstorms.

In parts of the Mystic, combined sewer overflows are also to blame for poor grades. This issue is most obvious in Alewife Brook, which has six active CSO outfalls.

Water quality in the Charles River is also affected by CSOs and stormwater runoff. Its most problematic tributary, the 3.5 mile Muddy River — which runs through highly paved urban areas of Boston and Brookline and then under Storrow Drive before meeting with the main body of the Charles — consistently gets poor grades because of the pollution carried into its waters during big rainstorms. An untreated CSO outfall also adds to the Muddy River’s problems.

While many of the tributaries and river segments that got Cs, Ds and Fs this year have received poor scores in the past, one area that appears to have had a particularly rough year was the lower basin of the Charles River — the segment that runs from Watertown to Boston Harbor. Thanks largely to heavy summer rainfalls in 2021 that caused nutrient-rich stormwater runoff and many CSO events, this portion of Boston’s iconic river dropped from a B to a B-. While this might not sound like a huge drop, these grades are based on a three-year rolling average, meaning last year’s water quality taken by itself would have yielded a lower grade.

Advertisement

“We hope these grades will spur members of the public to join us in demanding that local, state, and federal government leaders commit to eliminating CSOs, reducing polluted stormwater runoff, and investing in nature-based solutions to return the Charles to a fishable, swimmable river,” Emily Norton, executive director of the Charles River Watershed Association, said in a statement.

During 2021, CSOs in the Charles discharged about 126 million gallons of water containing sewage, fertilizer, pharmaceuticals and other harmful pollutants found on roadways, according to the report card.

The EPA began issuing water quality report cards for the Charles River over 25 years ago to help the public track the ongoing clean up progress. It began giving grades to the Mystic River in 2007, and added the Neponset River last year. Local watershed groups regularly collect and test the water samples, and then report the results to the EPA.

Given the record high temperatures and rainfall of last summer, this year’s report cards also highlight the threat climate change poses to these rivers and the ecosystems they support. In many ways, climate change is a recipe for water quality issues: Heavy rains drive nutrient-rich stormwater into the rivers through storm drains and CSO outfalls, and then warmer temperatures make it more likely that harmful bacteria and algae will proliferate.

One particular concern is cyanobacteria — also called blue-green algae — which look like splotches of green paint floating on the surface of the water. The algae produces a toxin that is harmful to humans and pets if ingested, though just touching it can cause skin rashes too.

Periods of drought, like the one Massachusetts is currently in, also create problems. Lower water levels can concentrate nutrients and cause the water that remains to heat up faster, both of which can harm a river’s ecosystem. According to David Boutt, a hydrologist at UMass, there’s growing evidence that climate change is increasing the frequency of short-lived summertime droughts in the region.

“Today’s reporting of water quality in the major urban rivers of Boston and surrounding communities underscores the hard work that has contributed to healthier waters, while also spotlighting locations and types of pollution that still need to be addressed,” David Cash, EPA Region 1 administrator, said in a statement. “All of our citizens deserve to enjoy a clean and healthy environment, especially in historically underserved communities.”

This year’s EPA report cards hold special significance since they come on the 50th anniversary of the landmark federal Clean Water Act. As noted in a joint statement by the Charles, Mystic and Neponset Watershed Associations, the Clean Water Act has been “a game changer” for water quality in these three rivers.

Prior to its passage, these rivers “were industrial dumping grounds, awash with raw sewage and toxic pollutants, inhospitable to plant and animal life,” the groups write. “By setting a broad vision for restored waterways and providing a regulatory framework to achieve it, the Clean Water Act provided the necessary leverage to hold polluters accountable and ensure clean, fishable, swimmable rivers for current and future generations.”

But while much progress has been made in the last few decades, environmentalists say there’s still a great deal of work left to be done in these three rivers — especially in segments that run through lower income and minority neighborhoods.

“For far too long, Boston’s environmental justice communities have been bearing a disproportionate burden of climate change and environmental hazards,” Rev. Mariama White-Hammond, chief of Environment, Energy, and Open Space for the city of Boston, said in a statement. “As a Dorchester resident, I dream of the day when residents along the Neponset River Watershed can swim in these waters with joy.”

Earlier this year, the EPA designated the lower Neponset River a superfund site, which should help fast-track its clean up.

In another river-related development, the Conservation Law Foundation and Charles River Watershed Association notified the EPA on Thursday that they intend to sue the agency over its “failure to regulate” the nutrient and pollution-rich stormwater runoff from industrial and commercial properties. While the Clean Water Act gives some regulatory exemptions to stormwater runoff, according to the two groups, several discharges into these three rivers are so detrimental to water quality that they deserve to be regulated.

The EPA declined to comment.