Advertisement

Bill Russell, Celtics legend and civil rights icon, dies at 88

Bill Russell, an all-time NBA great whose athleticism on the court made him legendary and whose outspokenness on social issues made him an iconoclast, has died at 88.

"Bill called out injustice with an unforgiving candor that he intended would disrupt the status quo, and with a powerful example that, though never his humble intention, will forever inspire teamwork, selflessness and thoughtful change," read a statement posted on Russell's official Twitter account.

Russell played center for the Boston Celtics beginning in 1956. Over the course of 13 seasons, he redefined the game of basketball, became the first Black head coach in the NBA and won 11 championships. Yet Russell, an outspoken advocate for civil rights, had a tortured relationship with Boston, which he once said was a "traumatizing" place to live.

And while many know Russell for being a great basketball player, through his words and activism, he made clear that he wanted to be known for more than being good at what he once called “a silly game.”

From West Monroe To West Oakland

Born on Feb. 12, 1934, William Felton Russell grew up in West Monroe, Louisiana, in a region shaped by Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. Lured by the promise of better schools and jobs, Russell's family moved to California in the early 1940s. His father Charlie and mother Katie took jobs in a shipyard, and the family settled in West Oakland.

Only a few years later, when Russell was 12 years old, his mother died after being hospitalized with flu-like symptoms. In his memoir, "Second Wind," Russell said that his mother's death severely impacted his self-confidence.

In a 2005 interview with NPR's Ed Gordon, Russell recalled, "My mother used to tell me that, 'You are as good as any person in the world. But you know better than any person in the world. And that is the way I want you to conduct yourself.'"

His father, however, continued to steer Russell toward his mother's dream that her son would one day attend college.

Advertisement

"My father was my hero," Russell said in "Mr. Russell's House," a documentary for NBA TV. "I was never afraid because I knew that he loved me."

While it may be hard to imagine, Russell was not preternaturally gifted at sports. Early on, as a student at McClymonds High School, his burgeoning height and lanky physique made him an awkward presence on the court and field. As such, he was cut from both the basketball and football teams. For a time, the only position he was allowed to hold was that of team mascot.

But George Powles, who later became coach of the basketball team, saw Russell's potential and allowed him to practice with the varsity squad. Russell improved, and later caught the attention of the University of San Francisco, which offered him a scholarship.

It was at USF that Russell blossomed as an athlete and an intellectual. Through games and late-night gym sessions, Russell began to master his own body and developed his unconventional approach to defense, which involved bounding into the air to block shots.

And whether he was walking through San Francisco, or traveling with the team, Russell often encountered racist attitudes and policies. Often during road games, Russell and his Black teammates would hear racial slurs from opposing fans, and they would not be allowed to stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as white teammates.

Despite these challenges, in 1955 and '56, he led the USF team to two consecutive NCAA titles — the first of many times he would earn the title of "champion."

As Russell's Star Rose, The Game Rose With Him

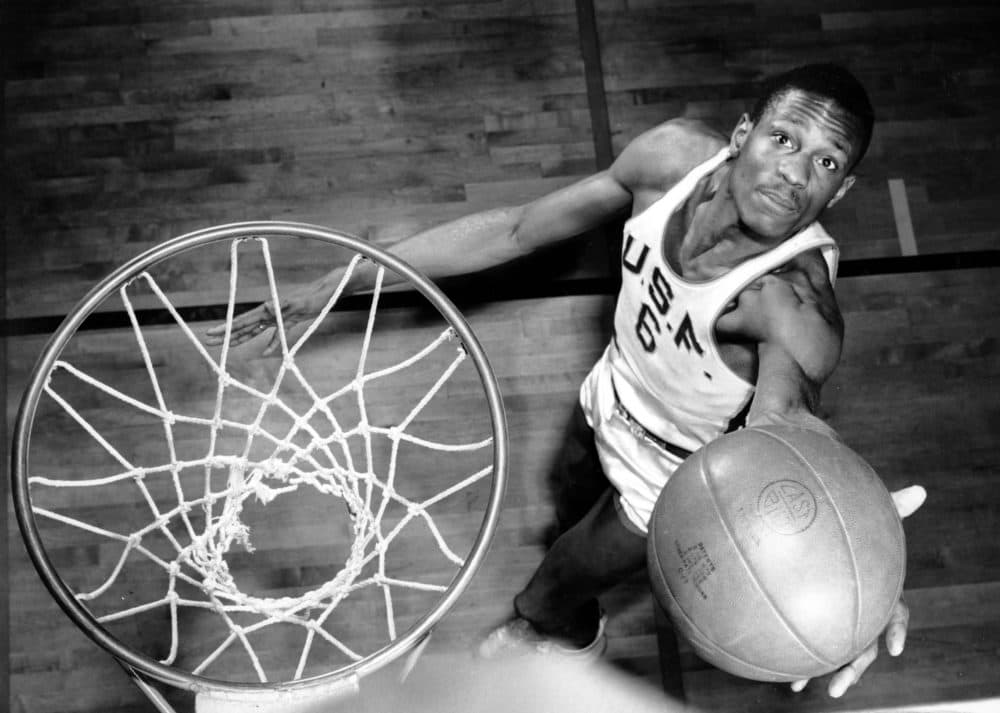

The period of 1956-57 was pivotal for Russell: only months after winning his second NCAA title, Russell won a Gold Medal playing for the U.S. basketball team in the 1956 Olympics. Soon after, he joined the Celtics, and in December of that year, he played his first game with the team.

For much of the '50s, the Celtics were a mediocre franchise, "a team struggling to find itself," said sportswriter Gary Pomerantz.

But "Russ changed the dynamic in every way," said former teammate Bob Cousy in a 2018 interview with WBUR's Only a Game.

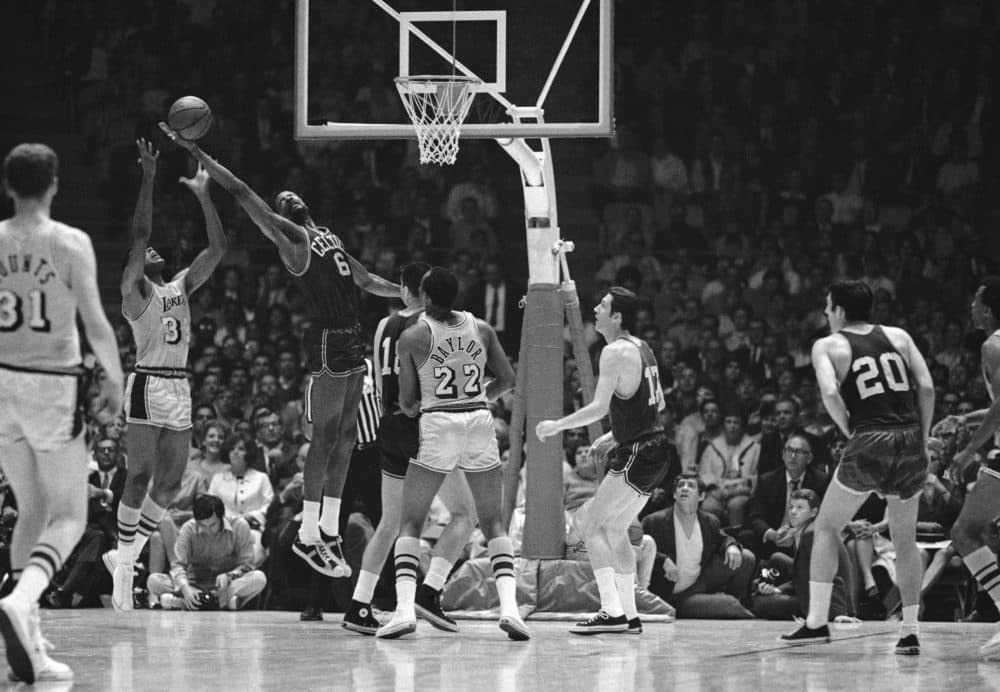

Russell brought startling athleticism, ferocious blocking and tenacious rebounding that ignited the Celtics' fast break offense. On top of that, he brought a fierce head-game.

"Basketball is a game that involves a great deal of psychology," he told Sports Illustrated in 1963. "The psychology is to make the offensive team deviate from their normal habits. This is a game of habits, and the player with the most consistent habits is the best. What I try to do on defense is to make the offensive man do not what he wants, but what I want."

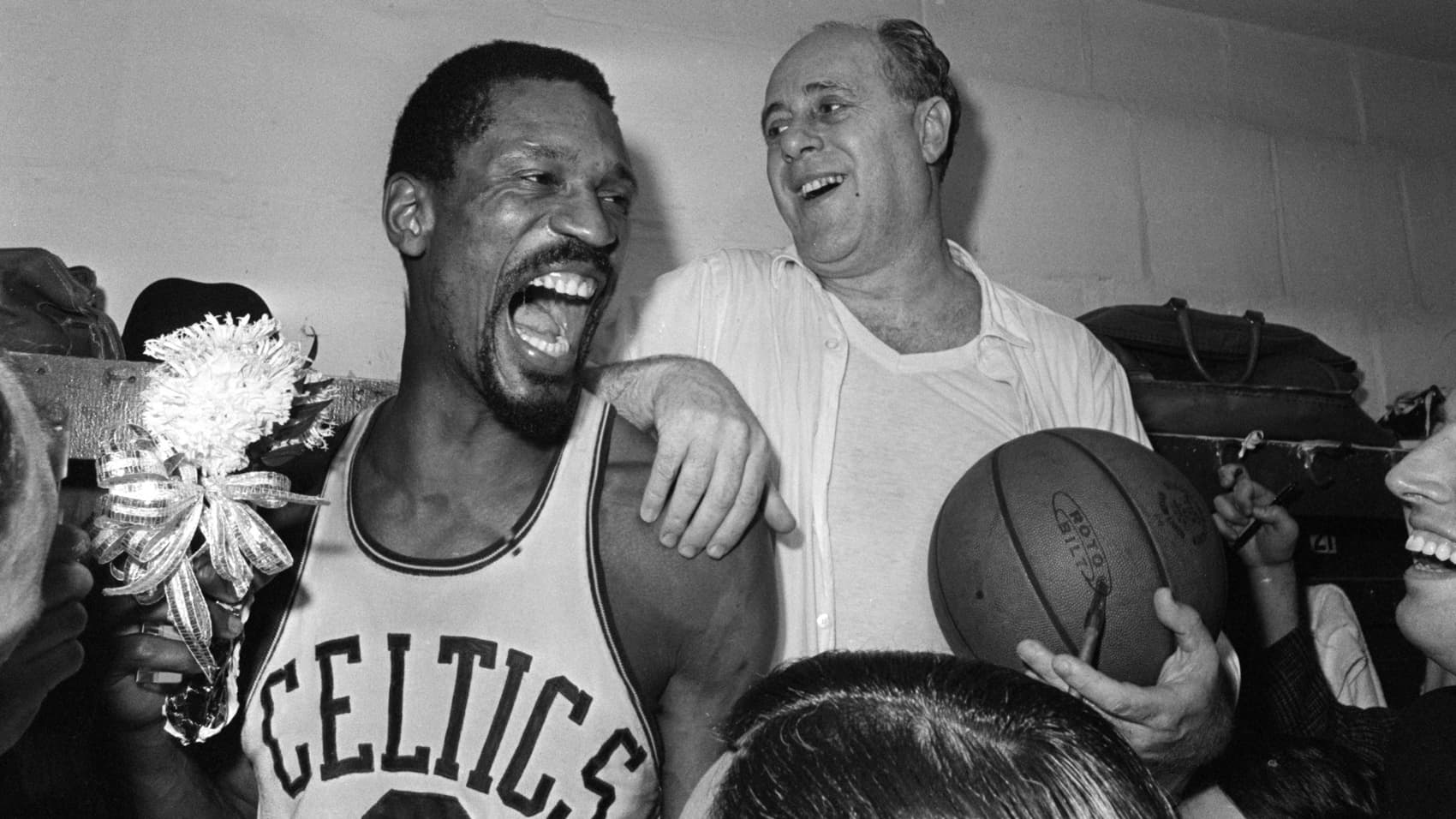

By the end of his rookie season, Russell helped the Celtics to win an NBA title. In the seasons that followed, Russell would lead the team to championship after championship.

Russell was a team leader, but also the ultimate team player. And although he was known to skip a practice now and then, his teammates let it go because it was clear how much he cared about winning. For instance, he often got so nervous before a game that he'd vomit in the locker room.

And after winning his 11th and final NBA title, Russell, with tears in his eyes, was momentarily speechless before composing himself in an interview with ABC's Jack Twyman.

"This is such a great bunch of guys, you know," he said. "And it’s just been so fabulous the way they played for me. It sounds all corny, you know, to start talking like that, but I told these guys before the game, I don’t care what happens, I wouldn’t trade you guys for any guys in the world."

When he took on the role of player-coach in 1966, he was the first Black head coach in the NBA. When reporters questioned whether he would have problems coaching white players, Russell brushed it off.

"I don’t anticipate any problems with the guys," he said. "Because one thing we’ve always had as the Celtics is mutual respect, and we think that’s the most necessary ingredient for a winning combination."

But Russell’s importance to the game of basketball went beyond winning championships.

"The simplest way to put it would be that Bill Russell changed the way that basketball was played," said Aram Goudsouzian, who wrote “King of the Court,” a biography of Russell.

In the 1950s, basketball was still a pretty earthbound game, Goudsouzian said. Offense was all about moving the ball in a position to get layups. But the 6-foot-9-inch Russell changed that when he left the ground, using his height and speed advantage to jump and block shots.

"He turned the blocked shot into a weapon, and once he did that, he erased the easy layup from the game," Goudsouzian said. To adjust, opponents started shooting from further away, leaping in the air and taking the now-familiar jump shot, rather than watching as Russell swatted away their layups. Because of Russell, the game became more airborne.

"In all these ways Russell’s defense creates modern basketball offense," Goudsouzian said.

A Legacy On Civil Rights

Russell’s impact also went beyond Boston Garden's parquet court to the national conversation about race and civil rights.

"We're a bunch of grown men playing a child's game,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1963. “It's a child's game we've made into a man's game by complicating it. Silly, isn't it? We entertain people for x-number of hours during the winter. They may talk about it for a few minutes, maybe an hour; then it's forgotten. Is this a contribution? No.”

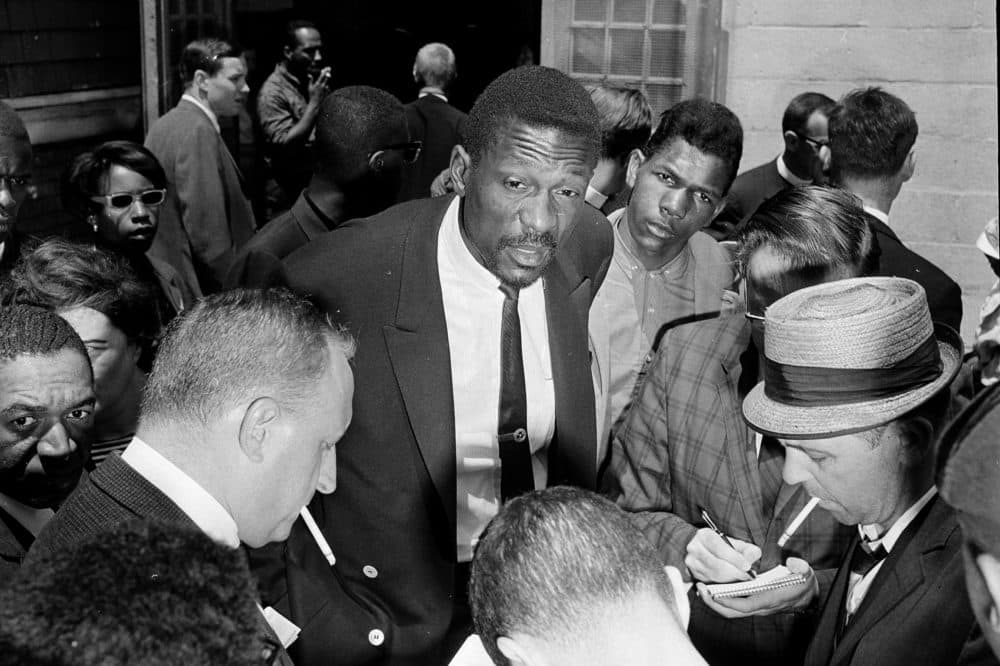

Early in his professional career, as a Black athlete in a mostly white league, he criticized other NBA teams for what he believed was an unofficial cap on Black players. Later, in the mid-'60s, Russell participated in the March on Washington, worked with the NAACP, and railed against segregated schools in Boston.

"This is a guy who went and conducted basketball clinics that were racially integrated in 1964 in Mississippi," Goudsouzian said. "This is the same summer as Freedom Summer, when activists were being murdered and harassed."

This level of activism was uncommon among high-profile Black athletes during the 1960s, said Harry Edwards, a sports sociologist and professor emeritus at University of California, Berkeley.

"Not only was it uncommon, it was unacceptable," said Edwards, who became friends with Russell through their mutual interest in using athletics as a platform to highlight and advance civil rights. "Even some Black people didn't understand — How can a guy with all this money, all this prestige ... be complaining about race relations in America?"

In this way, Russell, along with athletes like Jim Brown helped pave the way for others who sought to use their visibility to call attention to societal injustices.

"Not a lot of people came to Russell's support, in the ultra-conservative world of American sports," Edwards said. "He had to figure it out on his own."

A ‘Traumatic’ Relationship With Boston

Though Russell had close bonds with all his Boston teammates, white and black, that closeness did not extend to the city of Boston.

Russell often called Boston a racist city. During his time with the Celtics, he often said that it was the team, not the city, to which he felt allegiance. And, according to "King of the Court," after Russell retired from the Celtics and moved to Seattle to coach the SuperSonics, he called life in Boston “a very traumatizing experience."

The problems began the first time he and his wife at the time, Rose Swisher, visited the city.

"They land in Boston and they’re in a cab and they're heading toward the Boston Garden, and the [white] cab driver starts lecturing him about how to act, how to behave, what people expect out of athletes at this time," Goudsouzian said. "A very sort of patriarchal sense, and really rooted in a kind of racial hierarchy at the same time, and Russell immediately resents it, immediately bristles."

Even as his star rose, Russell took note of every insult, whether it was vandals breaking into his home in Reading while he was away and scrawling racial epithets on the walls, or a local sports writer asking a condescending question.

In an NPR interview, Russell reflected on his treatment by members of the press, who sometimes used the word "surly" to describe his demeanor: "When someone refers to me as 'surly,' especially when I was young, that to me was totally and completely race-baiting. The majority of society had decided on a code of conduct for minorities."

Unlike some of his teammates, Russell made little effort to cultivate a friendly relationship with the media.

"They didn’t like him because he exuded arrogance, confidence, and all other things that Black guys should not have in a lot of estimations," said former teammate Satch Sanders in an interview with WBUR's Only a Game.

Russell also felt bitter that the Celtics, a team increasingly made up of Black players, couldn’t draw as many fans as the Bruins. And he didn’t seem to garner the same love from hometown fans as white teammates like Bob Cousy did.

In the interview with Only a Game, Cousy said he regretted not showing more public support for Russell. “Russ was the ultimate 'angry Black man,'" said Cousy. "I didn’t blame him then and blame him even less now."

“I had a good relationship with the media. I always have," he said. "I could’ve reached out and perhaps shared his pain a little bit. I never did that with Russ.”

Because of these slights — or in spite of them — Russell for years refused to participate in the rituals of sports stardom. He famously didn’t sign autographs or glad-hand with fans. In 1972, when the Celtics retired Russell's jersey number (No. 6), he refused to go along with plans for a public dedication ceremony.

In 1975, when Russell was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame, he refused to attend the induction ceremony or accept a ring, in part because he felt other Black athletes deserved the honor first, and in part because he felt the Hall of Fame was a racist institution. Russell finally accepted the ring in Nov. 2019, not long after the Hall of Fame inducted Chuck Cooper, a former Celtics player and the first African American player drafted in the NBA.

In 2013, the city of Boston installed a statue at City Hall honoring Russell. It was the kind of lionization that he had often avoided.

"Two things about statues," Russell said at a ceremony unveiling the bronze sculpture shaped in his likeness. "First, they remind me of tombstones. And second, [it's] something that pigeons'll crap on."

Russell said that he only agreed to endorse the statue after former Mayor Tom Menino promised to create a mentoring program in the city.

Russell did not want to be worshiped or commodified. He wanted respect.

"There’s a difference between being proud and having pride," he said in an interview for an ESPN Classic documentary. "They may not like you but they have to respect you. And that’s more important. It’s more important, at least for me ... It is far more important to be respected than to be liked."

In other words, he wanted people to see him as more than a good basketball player. And he was.