Advertisement

Review

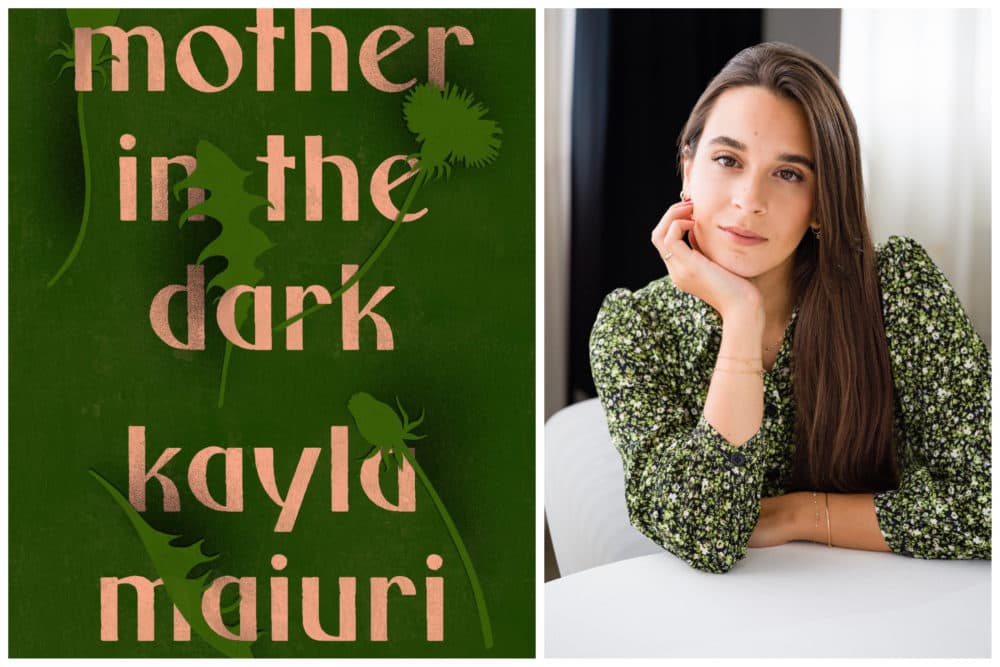

New novel 'Mother in the Dark' chronicles a family's struggle with mental illness

While I was reading “Mother in the Dark,” Kayla Maiuri’s novel of how a mother’s undiagnosed mental illness alters the lives of her family, “escape velocity” kept coming to mind: the force needed for a rocket to escape Earth’s gravity. It’s a power that Anna, the eldest of three daughters and the 20-something protagonist of this novel, could sorely use.

Anna lives in New York City, a deliberately long train ride from her family in Massachusetts, especially from her mother, Diana. But miles alone can’t prevent Anna from being caught in her family’s emotional pull, as she plays and replays scenes from her past. Anna grudgingly admires her roommate and longtime friend Vera, content in both her work and her new romance. In contrast, Anna feels stuck in neutral in all areas of her life.

To further muddle things, recent weeks have brought a flurry of voicemails from her father, Vin, and her two younger sisters. Anna lets the messages linger unopened. She doesn’t want to face what is certainly terrible news about, Diana. Because with Diana, it’s always terrible news.

Told entirely in Anna’s voice, “Mother in the Dark” (out Aug. 9) moves in two alternating storylines that ultimately merge. One is present day, which holds pivotal decisions Anna must make regarding her family, her work, and her friendship with Vera. Each decision tracks back to and serves as lead-ins for the larger story of Anna’s formative years.

When Anna was young, her family lived in a close-knit Italian neighborhood in Everett, a city just outside of Boston. Maiuri, who was born in Greater Boston, nicely conjures a teeming street of shoulder-to-shoulder tenements, Sunday dinners of homemade pasta and, as Anna fondly recalls, “always someone knocking on our door… always a neighbor yelling from her porch to ours.”

The social bustle only partially masks the fact that Diana’s moods veer unpredictably from warmly playful to a gloom so deep she can barely get herself dressed or make her daughters a meal. Or the fact that Vin, a construction manager, keeps himself a little apart from the other fathers. There are vague hints that Diana’s family harbors painful secrets, but mostly her actions are unexplained. Like the moon governing the tides, she is the central force in their home, for whom Vin and the three girls bend their behavior.

For a child of a troubled mother, the difference between barely surviving or nearly thriving can be to have other caring people around. The Everett community amply provides that for Anna and her sisters. That is, until Anna is 10 years old, when Vin unilaterally decides to move their family to a new development his construction company is building in Topsfield, a rural town about 20 miles north of Everett. He presents it as a great opportunity: the girls will each have their own bedroom, they’ll attend better schools, they’ll have more places to play.

Advertisement

The suburban ideal quickly turns into a nightmare. Anna recalls that, isolated in the sparsely populated development, Diana’s behavior became “stranger, her actions more erratic. She cried for no reason, or else she paced the halls like a ghost in search of something.” The parents’ arguments, on simmer back in Everett, now blow up into ugly shouting matches, with Vin the exasperated voice of reason and Diana the disheveled martyr.

As the sisters progress through middle school and high school, Diana becomes both more fragile and more scheming, pitting the daughters against their father or each other, with what Anna comes to consider her “sick love.” To combat this, the sisters create their own protective community. With compassion, Maiuri shows their evolving bonds of love and friction.

Yet, though many individual scenes are well written, the Topsfield chapters are weighed down by too many similar events and descriptions. Year after year, Diana’s hold on reality slips and catches and slips again; kitchen cupboards are again nearly empty of food; Vin works and drinks, and drinks some more. When a calamity inevitably occurs, there is little feeling of “before” and “after.” Life continues to edge forward, just worse by a few degrees.

This all makes “Mother in the Dark” read more like a chronicle than a novel with a full narrative arc. Sealed within these details is a deeper story of the cost, to all members of a family, of ignoring mental illness from one generation to the next, and the poignant tale of a daughter struggling to come to terms with and to escape this toxic cycle. But to fully tell it, “Mother in the Dark” needs to rise above a long accumulation of days.