Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

One idea to reduce coastal flooding in Boston: create an artificial wetland

Chained between rusty beams on Chelsea Creek in East Boston is a big, floating ball of plants.

It's made of wood chips encased in coconut fiber and netting, with marsh grass growing on top and seaweed underneath. And it's heavy; the pod weighs in at about a ton when waterlogged.

This bobbing ball is part of a test run for a new climate resiliency project: The Emerald Tutu. It's a system of floating wetlands designed to reduce coastal flooding by knocking down waves. Boston is projected to see increasing flooding in the coming decades because of climate change.

“Fundamentally, it’s like a giant sponge that fits around urban coastlines like we have here in Boston,” said Gabriel Cira, the project lead. “It buffers those coastlines from the intense effects of coastal storms.”

Of course, the actual function of the Tutu is a bit more complicated than the sponge in your kitchen sink. In theory, hundreds of individual pods would be linked together and anchored to the ocean floor. When waves come through, they would hit these clusters first, lose energy, and then come to shore smaller and with less force.

Because they're made of individual plant-balls, the system can also adapt to different kinds of shorelines.

“We can add more, we can add less, we can pull them closer together, we can move them further apart,” said Julia Hopkins, the project’s lead scientist and an assistant professor at Northeastern University in civil and environmental engineering. “We can maintain it such that you can keep pace with storms, rising sea levels, and things that would happen with climate change.”

The test unit in Chelsea Creek is the latest iteration of the project, which was originally developed as the winning entry at the 2018 MIT Climate Changed ideas competition. The research team was later awarded a National Science Foundation grant.

Advertisement

Since then, they've had success figuring out how to arrange the pods to reduce waves in test runs in Oregon, where researchers hit chains of the plant-balls with waves from a simulator. The module in the East Boston is expected to stay in place for several months, and the team is planning to run larger-scale tests of linked pods in the coming year.

East Boston is one of the city neighborhoods most prone to the kind of flooding the Tutu is trying to address.

At the Shaw’s Supermarket near Liberty Plaza, John Walkey, director of climate justice and waterfront initiatives at GreenRoots, pointed to the short drop between the parking lot and the waterline.

“This happens to be one of the flood pathways that’s been identified by the city of Boston,” he said. "The seawater comes right in ... so the ducks and the geese will just sort of float along into the parking lot and just keep floating along into a parking space.”

A recent UMass Boston report found the city could see high-tide flooding — also known as nuisance flooding — an average of 180 days a year by 2050; right now, we see this kind of flooding about 15 days a year.

“Twenty, thirty years from now, Liberty Plaza is flooded, parts of Maverick Square are flooded, the Sumner and Callahan Tunnels are flooded,” said Paul Kirshen, professor of climate adaptation at UMass Boston and one of the report’s co-authors. “Instead of being an occasional nuisance it would be happening a lot."

East Boston is an environmental justice community. In addition to the flooding, residents here face higher rates of air pollution, asthma, and chronic heat. The neighborhood has also been a hub for low-income and immigrant communities. Though it has been gentrifying with increased development, East Boston has a lower median household income than the rest of the city, and the highest percentage of immigrants.

There are also remnants here left behind by polluting industries; the Emerald Tutu team is testing their new pod at the Hess Site, named for the Amerada Hess Corporation that once owned the area and used it as a fuel tank farm. The East Boston Community Development Corporation now owns the site, and gave the researchers access.

Because of this history, and the severity of the climate problems, there’s extra pressure to make sure the Tutu not only works as intended, but also takes into account the local community.

“There are developers and folks from the city, and then folks from community-based organizations suddenly reaching out to community members saying ‘we want to know what you think, and what’s your vision for East Boston 15 years from now?’ ” said Walkey. “And you’re talking to someone who’s thinking that they may not be able to stay in their apartment next month. So there’s a disconnect.”

The Emerald Tutu researchers have taken steps to close that gap. They’ve now worked within East Boston for several years, and attended multiple community meetings to share the project. They’ve also reached out to GreenRoots and other local organizations that have long worked in East Boston on climate and accessibility issues.

One of those organizations was Eastie Farm; Cira was the architect of the nonprofit’s new climate-friendly greenhouse. The farm’s director, Kannan Thiruvengadam, and several other volunteers were part of the group that helped install the Tutu pod in early July.

“I was excited to see how that happens,” said Thiruvengadam, “and when you’re there and another pair of hands are needed, you want to help.”

Thiruvengadam is optimistic about the Emerald Tutu, and the role it could play in East Boston’s future. Part of the group’s mission is to provide opportunities for citizen science, and potential local jobs on production and maintenance if the full system works.

But that end goal is still far away. The Tutu is at least a few years from being operational, and the researchers still have more tests to run.

No one thinks the Emerald Tutu will be the silver bullet that saves East Boston from climate change.

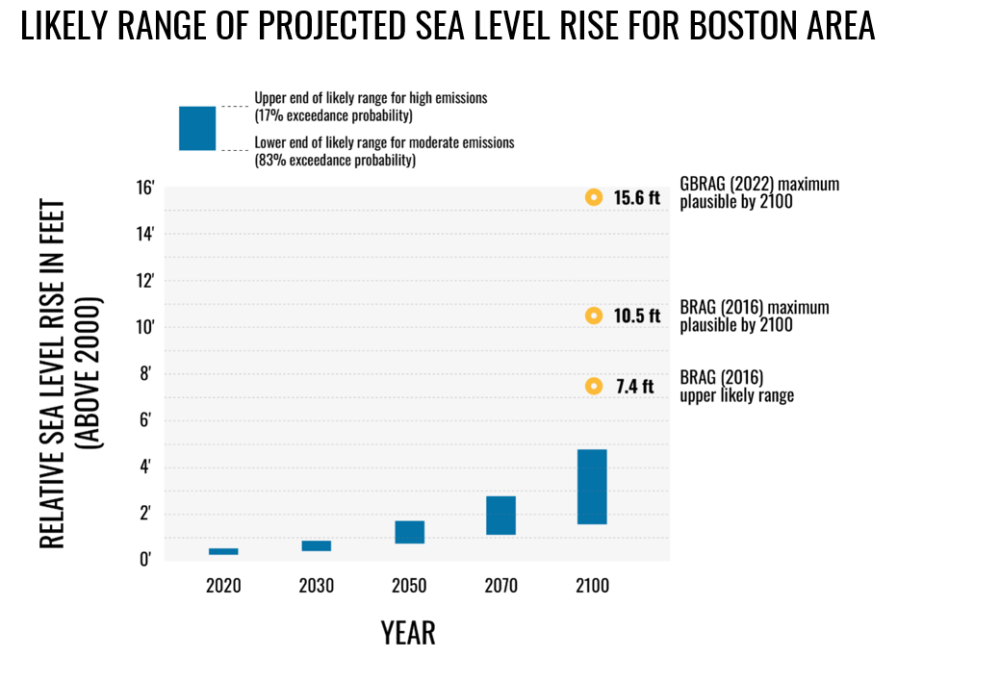

Floating wetlands have been used in other states as ways to improve water quality and habitat, but they aren’t historically designed for flood protection. The system can’t stop sea level rise — Boston has one of the highest rates of sea level rise in the world, and is expected to see 4.8 feet of increase by the end of the century — and there are questions about how well the pods hold up in a violent storm.

The problems facing East Boston and the rest of the city are severe. In addition to community plans like the Emerald Tutu, the City of Boston has plans for berms, raised walkways, and a deployable seawall to block part of the neighborhood’s greenway.

“It’s all hands on deck,” said Paul Kirshen, from UMass Boston, “any idea that’s reasonable should be looked at.”

For many watching the Emerald Tutu take shape, there’s hope that one day, it will be one solution of many.

This segment aired on August 11, 2022.