Advertisement

Review

Coolidge Corner and Brattle Theatres revisit the late Jean-Luc Godard

Director Jean-Luc Godard sometimes cheekily liked to credit himself as “Jean-Luc Cinema Godard,” an ostentatious but not inaccurate handle for an artist who lived and breathed movies while spending a lifetime blowing up their boundaries. When he died last month at the age of 91, critics were quick (and correct) to eulogize him as film’s Pablo Picasso or the cinema’s James Joyce. Godard movies did things you didn’t know movies were allowed to do – drolly and often obstreperously expanding our ideas of what is possible in the art. His final film, 2019’s “The Image Book” was as radical and revolutionary as his first, a capstone to six decades spent pushing viewers to discover new ways of seeing.

The closest career analogy is probably to that of Bob Dylan, with initial superstardom followed by just as many artistic metamorphoses, intensely debated phases and disavowed allegiances over the years --- and in a bizarre coincidence, near-fatal motorcycle accidents that almost took them both out early on. Like Dylan, Godard re-emerged as an enigmatic elder statesman with a late-career masterpiece (“Goodbye to Language 3D” was his “Time Out of Mind”) but much like with Bob’s music, most folks still seem to dig his ‘60s stuff the most. This is probably why both the Brattle Theatre and the Coolidge Corner Theatre are remembering Godard this week by screening three of his wildest and most freewheeling early efforts: 1960’s “Breathless,” 1964’s “Band of Outsiders” and 1965’s “Pierrot le Fou.”

What a mischievous trio! These are the works of a merry prankster intoxicated by the possibilities of the medium, pushing at its limitations and discovering there are none. Deceptively lighthearted tales of heartbreak and folly, they’re films about foolhardy men trying too hard to be the stars of their own movies, chasing women they’re incapable of understanding. All three stories come to tragic ends, yet what we mostly remember is how funny and cool they are – full of absurdist asides and knowing nods, flights of sublime silliness amid stylish poses and half-kidding crime plots. These are important landmarks in terms of understanding cinema history. But more importantly, they’re so much fun to watch.

Godard was not the first of his colleagues from the French film journal Cahiers du Cinema to go out and direct a picture of his own, but the blockbuster success of “Breathless” cemented the Nouvelle Vague as a bona fide movement. The Cahiers critics – of whom Godard was one of the most cantankerous – championed then-disreputable crime movies and Westerns over the more celebrated Hollywood prestige pictures of the day. (Godard was scoffed at for calling Howard Hawks the most important American artist of his era, an appraisal to which the ensuing years have been extremely kind.)

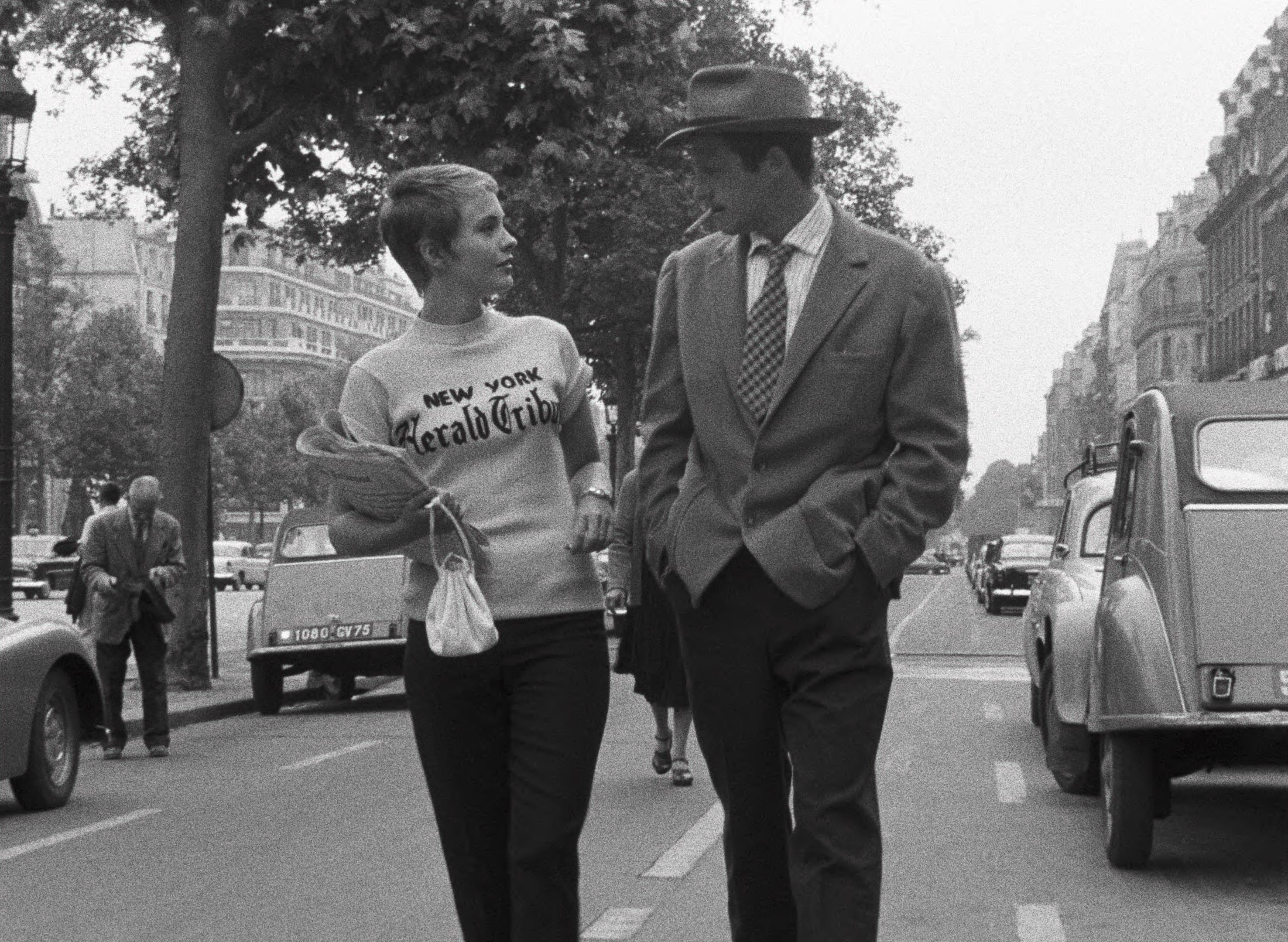

“Breathless” is, among other things, an act of film criticism. Godard takes what could pass for the plot of a poverty row B-movie and filters it through his European intellectual sensibility. Jean-Paul Belmondo stars as Michel Poiccard, a two-bit hood who idolizes Humphrey Bogart and practices trying to smoke cigarettes like him while staring into the mirror. On a whim one day, Michel steals a car, kills a cop and is on the run to Rome, but first makes a quick stop in Paris to try and talk his elusive American girlfriend (Jean Seberg) into going with him. The film’s frisky frictions come from all the high art allusions rubbing up against the lowbrow crime story, playfully placing a philosophical French movie within a dime novel context.

Belmondo was never more loveable than when working with Godard. Michel is a curiously soulful sociopath in a fedora and suit that’s a little too big for him, play-acting as a gangster the way he learned from the movies. Seberg is already the ultimate unattainable beauty from her instantly iconic entrance, selling American newspapers on the Champs-Elysees in a pixie cut that quickly became a craze. (I once read somewhere that 20 percent of “Breathless” is closeups of Seberg, one of those statistics that even if it isn’t true feels like it should be.) She’s one of the most unavailable beauties ever seen onscreen, impossible to read. Yet like the doomed Michel, we can’t help but keep trying.

Godard trashes conventional movie continuity by jump-cutting around during scenes, expanding and contracting the passage of time in ways alienating and invigorating. Cinematographer and former war correspondent Raoul Coutard invented new ways to bring the camera out into the Paris streets, with a then-shocking handheld mobility that’s probably impossible for us to properly appreciate today, as such innovations have become so commonplace. Still, the movie is always calling attention to its own artifice and reminding you that you’re watching a movie. Much like its protagonist, “Breathless” is constantly looking at itself in the mirror.

Quentin Tarantino named his first production company A Band Apart, an anglicization of “Bande à part,” the French title of Godard’s “Band of Outsiders.” A fitting tribute, as it’s impossible to imagine Tarantino’s brand of italicized pulp fiction without the arch influence of this effervescent caper, which starred Godard’s then-wife and muse Anna Karina as an idle student swept up in an ill-advised armed robbery scheme by two classmates competing for her affections. Their criminal activity is almost an afterthought, subordinate to our dangerously bored young folks trying to pass the time with stunts like attempting a minute of silence (the film’s entire soundtrack drops out) or racing through the Louvre in record time, ignoring all the art.

My favorite scene in any Godard movie is a musical number that occurs midway through the film, with the three prospective criminals at a café, deadpan dancing the Madison in perfect time while our wry, omniscient narrator (voiced by the director, naturally) “opens up a parenthesis” to tell us what they’re really thinking, expressing concerns both profound and somewhat less so. It’s one of the funniest and most delightful dance sequences ever filmed, and without it I daresay you never would have seen Vincent Vega and Mia Wallace doing the twist at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

The Brattle is presenting “Breathless” and “Band of Outsiders” as a double feature this week. I happened to catch the same double bill as a freshman in college at the Theatre 80 St. Marks in the East Village way back in 1993, and will never forget staggering home to my dorm room dizzy, feeling like all of my critical circuitry had just been rewired. The only thing I could be sure of was that I was going to be in love with Anna Karina for the rest of my life.

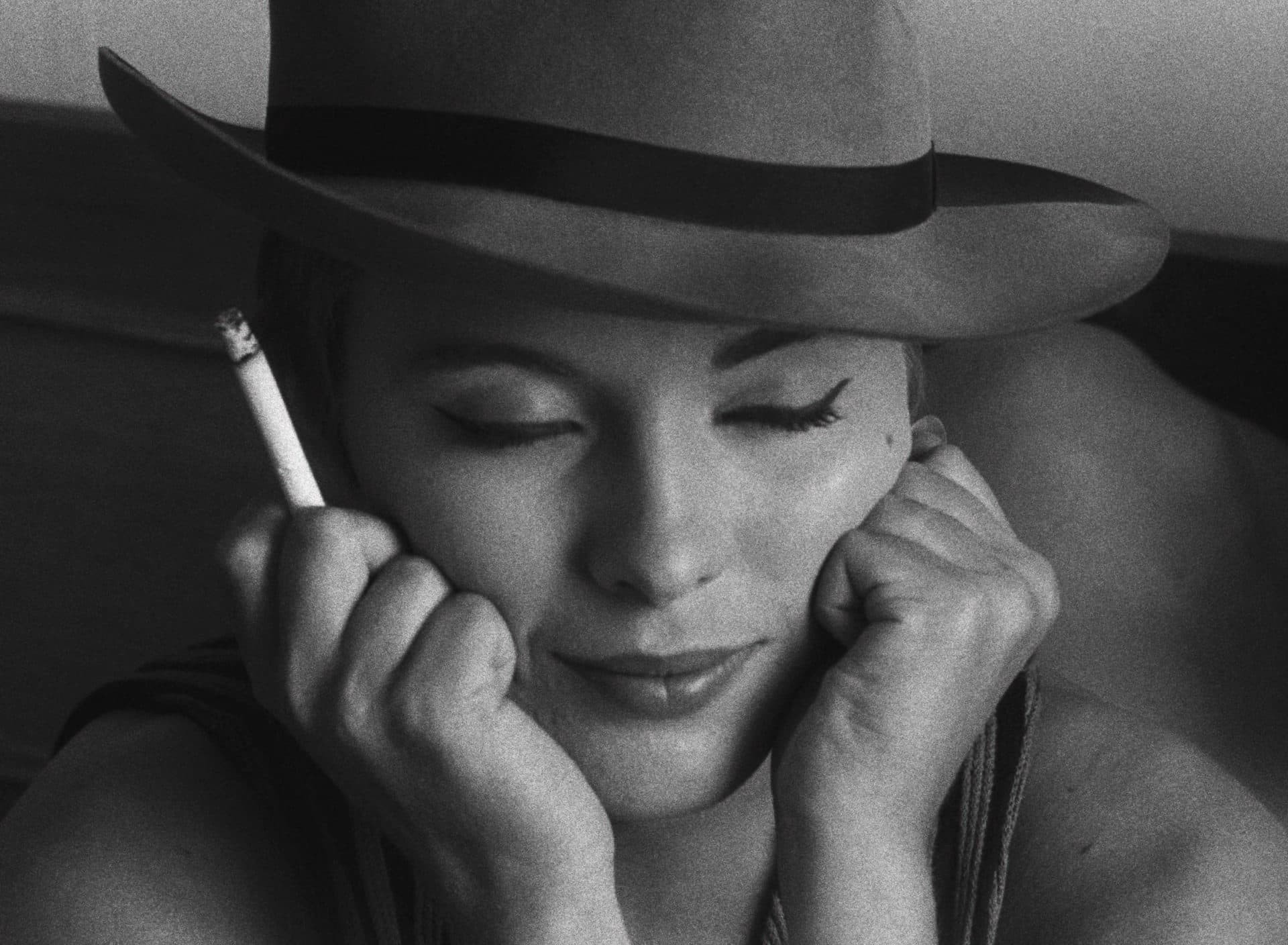

A similar fate befalls Ferdinand Griffon (Belmondo, again) in Godard’s “Pierrot le Fou,” a depressive, suburbanite dad who runs off one night with the babysitter (Karina, again) and finds himself mixed up in some sort of gun-running intrigue in Algeria. That snarky unseen narrator in the black-and-white “Band of Outsiders” had promised us that the next adventure would be in Technicolor and CinemaScope, and “Pierrot” might be the most spectacularly beautiful of Godard’s films, not just for the closeups of Karina.

They were divorced by then, or were at least in the process during filming. (She's said they only communicated on the set through snarls.) And yet I’ve seldom seen a director’s camera worship a woman quite like this. Ferdinand keeps throwing his life away for her time and time again, with the two endlessly finding new ways to make each other crazy, while we in the audience nod because we understand. “Pierrot le Fou” is both a dizzyingly romantic road picture and suffocatingly cramped and nihilistic, with Godard pioneering the collage process that would become more prominent in his later career, cutting away to great artworks with recitations of incongruous literary quotations on the soundtrack. The most telling scene finds Belmondo wandering anesthetized through a fancy-schmancy bourgeoisie cocktail party where everybody only speaks in advertising slogans.

In “Breathless,” Seberg is seen interviewing a famous author and possible Godard stand-in played by the great French crime movie director Jean-Pierre Melville. She asks him his greatest ambition and he replies: “To become immortal, and then die.” Mission accomplished. Adieu, Jean-Luc.

“Pierrot le Fou” screens at the Coolidge Corner Theatre on Monday, Oct. 10. “Breathless” and “Band of Outsiders” screen at the Brattle Theatre from Tuesday, Oct. 11 through Thursday, Oct. 13.