Advertisement

Review

Gold at the Gardner: Paintings 700 years apart have some things in common

I was dubious. What would a 14th-century Italian religious painter have in common with three living artists? But “Metal of Honor: Gold from Simone Martini to Contemporary Art,” skillfully assembled by Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum curators Nathaniel Silver (Renaissance) and Pieranna Cavalchini (contemporary), confirms that art is art, no matter what the period, and the juxtaposition of old and new creates illuminating reflections and reverberations.

In some way, the title of the show is a little misleading, since the “to” in “to Contemporary Art” should probably be more accurately an “and,” since the show actually leaps from paintings by the 14th-century Sienese master Simone Martini to the 21st-century African American artists Titus Kaphar, Stacy Lynn Waddell and Kehinde Wiley. What they all have most obviously in common is the dazzling gold leaf used as backgrounds (or foregrounds) in all the paintings on display. (Wall copy helpfully describes the various techniques—the “how-to”—of applying gold leaf to a board or canvas.)

Isabella Stewart Gardner acquired her two Simones just before the turn of the 20th century, which made her and the museum she was planning the possessor of the first paintings by this artist in America. These paintings still remain double the number of Simones in any other museum on this side of the Atlantic. One of the paintings is a small Madonna and Child, about 13 by 10 inches, with four tiny saints and a nun kneeling in prayer in raised gesso on a band running across the bottom of the main image (called an “arcade,” since these figures are separated from one another by tiny pillars). For the first time, we can also now see that the reverse side was evidently intended to be a mirror for self-contemplation.

The Gardner’s other Simone is far larger—a five-panel polyptych nearly 9 feet wide and a little over 5 feet high. A “Virgin and Child” is in the center, flanked by two saints on each side, with a risen Christ and trumpet-playing angels looking down from smaller panels above them. It’s the largest and most complete Simone Martini altarpiece in America. In their usual positions in the museum, neither of these masterpieces was easy to see. They are now.

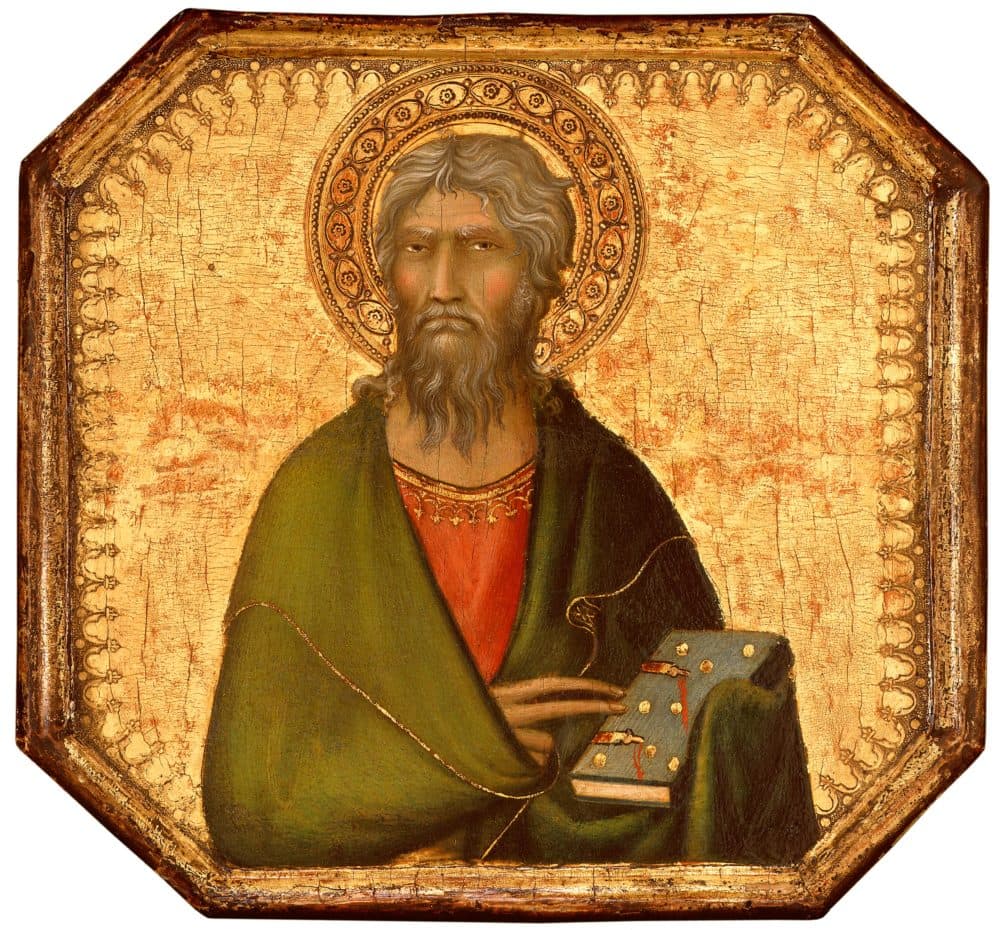

Amazingly, the Gardner was also able to borrow four other paintings, making this the largest ever Simone Martini exhibit in this country. These include a radiant “The Virgin and Child” from the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, a glowing “Saint Catherine of Alexandria” from the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and two smaller paintings—a stern “Saint Andrew” from Boston’s MFA (which I can’t remember having ever seen exhibited), and a saint with a book, weeping (you can see the teardrop), from Birmingham, England.

Of course, the first thing that strikes you is the exquisite goldwork, both the intricate decoration surrounding the figures—the world of these figures—and the dazzling little details on their robes and headpieces. But the gold quickly becomes secondary to the beauty and humanity of the images themselves, and the wonderful details they are filled with. In the Gardner’s “Virgin and Child with Saints,” the baby Jesus clutches the edge of his red garment and looks out at us. The lovely Madonna, with the baby in her arms, is also looking out at us, but more sideways. Then you notice the infant’s tiny feet sticking out from between her fingers.

Advertisement

Even more touching, in the Nelson-Atkins painting, the child is yanking on a dangling part of the Madonna’s veil or head shawl. In the upper corners, two saints are each contained in their own little circle, but one of them, John the Baptist, is pointing down at the mother and child, and his outstretched arm is breaking through the border of his roundel. In the little “Saint Andrew” painting, the saint seems to be leaning his elbow on the painting’s frame.

Maybe my favorite detail, in the centerpiece of the polyptych, is the baby tenderly caressing his mother’s chin. To which she responds with calm acceptance as she sees into the child’s future. I can’t help remembering a Simone Martini that isn’t in this show, which may be his greatest painting: the magnificent, almost life-size “Annunciation” in the Uffizi, in Florence. In it, the angel Gabriel has come to tell the young virgin the astonishing news. But she doesn’t accept it. She twists away, terrified, and squinting at the angel in dismay. This is news she doesn’t want to hear. It’s in startling comparison to the tenderness she shows her child in these paintings at the Gardner.

One thing all these paintings have in common is the intensity in the eyes. Whether we see eyes straight on, looking out directly at the viewer, or turned to the side, looking—or avoiding looking—at each other, or at anyone, in their various gazes every eye is penetrating, even searing. With all the dazzling and brilliantly worked gold around them, it’s those eyes—every figure’s eyes—that magnetize our own gazes. I think it’s those piercing eyes—eyes that seem at once both very human and otherworldly—that differentiate Simone from all his contemporaries.

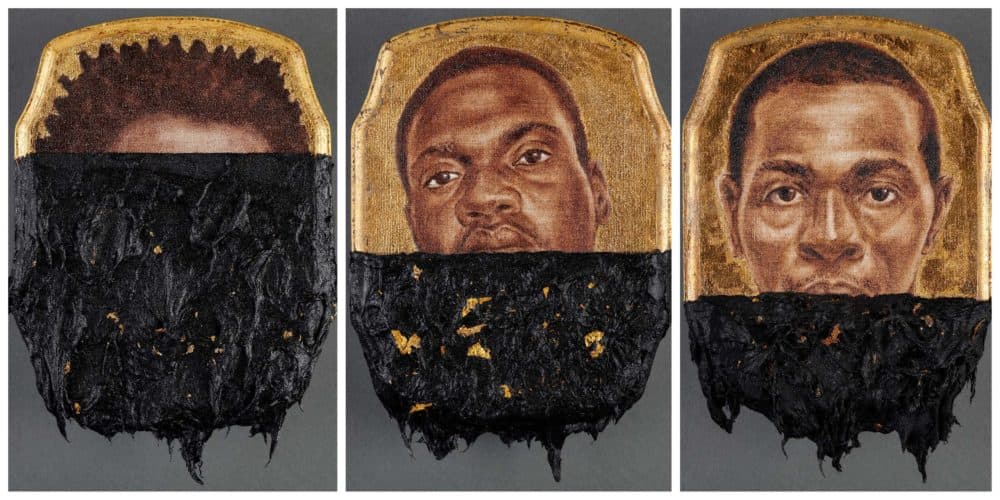

But we’re not done with eyes. Most of the Simone Martini paintings are in the small room at the entrance to the Gardner’s Hostetter Gallery. The Gardner’s big altarpiece is the only Simone in the main gallery, in the middle of the room. It’s encircled by the paintings of the three contemporary artists hanging on the surrounding walls. And it’s the eyes in the two large works by Titus Kaphar that hit you hardest.

These two pieces—“My Loss” and “State Number 2 (Dwayne Betts),” each about six feet high and five feet wide—are a continuation of Kaphar’s earlier series “The Jerome Project,” from which 15 smaller works, mostly dating back to 2014 and 2015, are on view in the Gardner’s Fenway Gallery in the old building. It’s a remarkable undertaking. The wall copy tells us that these portraits were based on mug shots of imprisoned Black men who all have the same first and last name as Kaphar’s father. There are now 97 of them. Kaphar says, “I began to paint those mug shots as…religious style paintings with gilded backgrounds. I then submerged those paintings into tanks of tar based on the amount of time that these folks had spent incarcerated.” The rectangular format is altered by concave corners to suggest the external force that’s pressing in on the inmate.

I hesitate to call these works simply paintings because the heavily textured tar is so sculptural and tactile—and oppressive—while the gold leaf conveys something spiritual about these faces. No face is seen complete, but the eyes give everything away. In the two large paintings in the room with the Simone Martini polyptych, the eyes are clearly visible above the tar line; in one of the 15 miniatures in the Fenway Gallery, the tar line comes up just below the eyes; and in three of these, the tar covers even the eyes. These are heartbreaking images, and real portraits. The eyes we can see—suspicious, defiant, innocent, desperate, confused, pained, scared—tell us everything we need to know about each subject.

Stacy Lynn Waddell is the Gardner’s current artist-in-residence. A massive and endearing photograph of her grandmother is reproduced on the façade of the new building. Three of her paintings are in the “Gold” show, and they are particularly striking because each surface is entirely in gold, all employing techniques developed by Simone Martini. Waddell’s “Woman in a Checkered Dress in Contrapposto (For M.S.)” is based on an image by the West African photographer Malick Sidibé, from Mali. Depending on the way light hits the surface, the gold leaf makes the Malian woman in the painting either powerful or invisible—which is precisely Waddell’s point about the duality of Malian women. The wall copy advises the viewer to move from right to left so that we can catch the various ways the light falls.

The best-known of the three contemporary artists is probably Kehinde Wiley, the artist famous for painting Barack Obama for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Gold is only one of the elements with which Wiley re-creates devotional altarpieces for his Black saints. Are they really images of the saints in his titles, or of the secular, highly sexualized modern figures, whose real names are inscribed on each altarpiece? Erotically twining flowers pervade the painted surface. Are they our contemporary saints? “Icons,” Wiley writes, “are demure… And they’re loud—they’re gold and they’re blinging all out of nowhere… I’m in love with that vocabulary. I wanted to create a body of work that… fused the sacred and the profane. This notion of the sacred, pure, untouchable space where divinity rests sort of muddied and sullied by this perceived notion of the Black body.”

I’m reminded not so much of Simone Martini’s devout explosions of gold as of the glistening skin and hollowed-out faces in paintings by Botticelli or Crivelli (both in the collection of the Gardner)—almost seen through the modern, super-realistic eyes of Mapplethorpe. It’s almost too much, but the works of Simone nearby, with their more traditional sense of religious devoutness, help keep our focus on the tension in all these paintings between the spiritual and the worldly—an undercurrent of this entire memorable exhibition.

“Metal of Honor” (along with “The Jerome Project”) will be on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum through Jan. 16. On Nov. 17, award-winning poet, lawyer and author Reginald Dwayne Betts will be in conversation with three other activists — Stacey Borden, Erika Rumbley and André de Quadros — on the subject of “mass incarceration, creativity, and healing” at the Gardner’s Calderwood Hall.