Advertisement

At the MFA, abstract painter Frank Bowling finally gets his due

In 1976, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston acquired Frank Bowling’s “Suncrush,” a tropical technicolor delight that nearly leaps off the wall with vibrant energy. The museum showed it briefly a year later before storing it away for the next 42 years, showing it briefly for the 2019 exhibition “Contemporary Art: Five Propositions.”

That happened a lot to Bowling. At the time, he was a Black abstract painter working in a titanium white art world.

Now, in the first true solo exhibition of his work in the United States, Bowling — a British Guyana-born London-based painter, alive and still painting at the age of 88 — finally gets his due. In “Frank Bowling’s Americas,” opening at the MFA Oct. 22 and running through April 9, American art fans can finally revel in work created by Bowling during his seminal years in New York between 1966 and 1975.

“It just felt like a very timely thing to do on an artist who we have had in the collection for a long time,” says Reto Thüring, chair of contemporary art at the MFA and curator of the exhibit. “I looked into the exhibition history here in the United States and realized that since the Whitney's solo exhibition in 1970 —which was a really small exhibition only comprised of four paintings— he had never had another solo exhibition in the United States.”

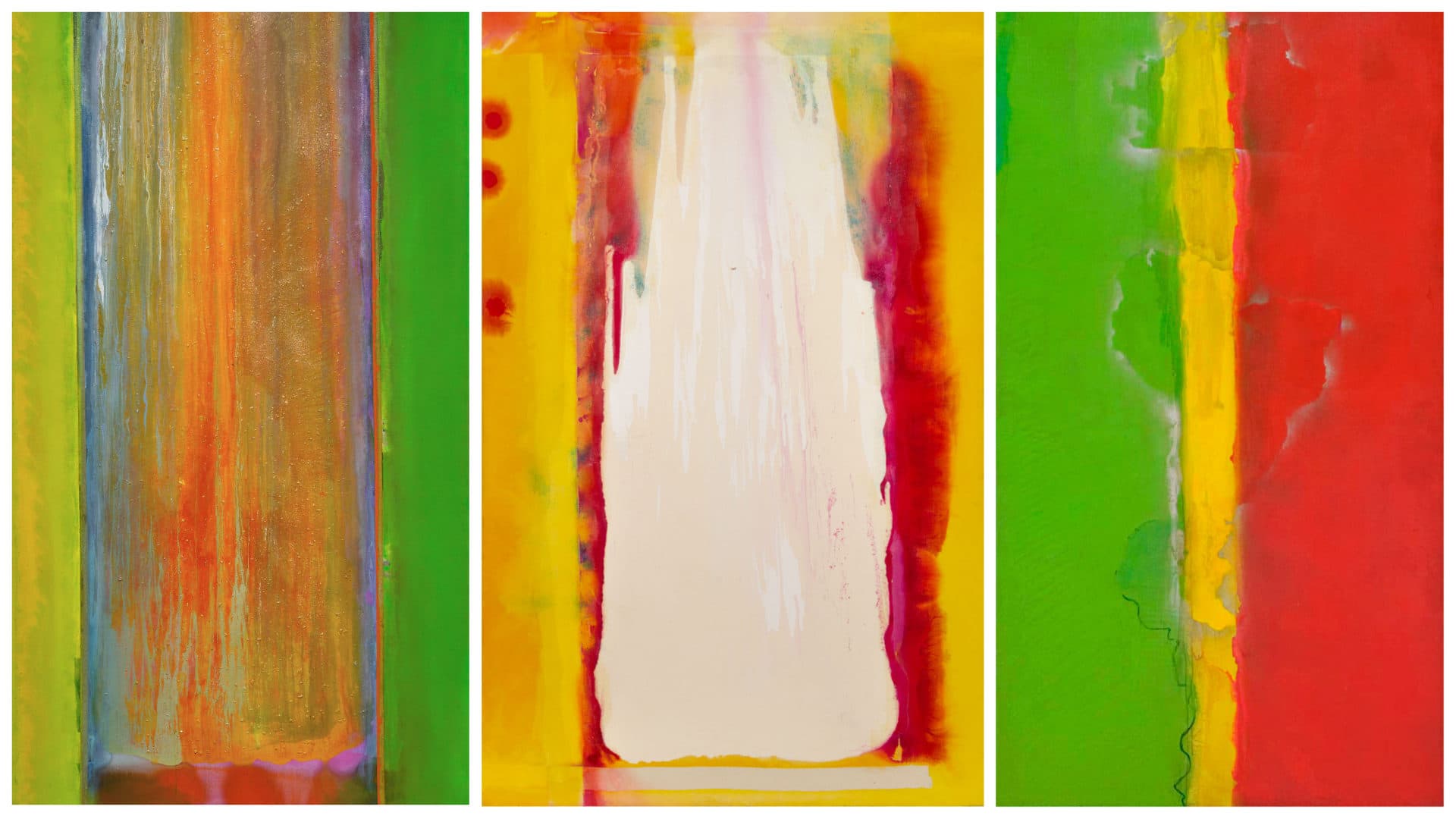

Bowling’s paintings, color field canvases of luminescent hues and poured paintings featuring vivid acrylics that dribble seductively down the length of a canvas, have largely been overlooked by the art world aristocracy. His work, in fact, only began to catch the attention of curators and collectors after it was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2003. In 2019, Tate London finally held a major retrospective, and that same year, Hauser & Wirth presented a single exhibition of his work in both its London and New York galleries.

What led to such a glaring omission?

Certainly, art world racism is likely to have played a role.

When Bowling arrived in New York in 1966, the art buzz of the moment surrounded abstraction, and particularly the work of mostly white, mostly male, artists like Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Jasper Johns, Morris Louis, Clyfford Still and Kenneth Noland. Bowling, influenced by English landscape painting and artists like Francis Bacon, created pieces with some figurative elements.

Advertisement

At the same time, Bowling also stood outside American art movements of the late ‘60s like AfriCOBRA, the movement declaring that Black artists should be making art overtly dedicated to uplifting the Black race through a “Black aesthetic.”

In fact, as a Black British man, Bowling was an outsider in every respect, be it race, country, or artistic direction, although he consistently produced work bettering that of many of his peers. Bowling found entrée into the New York arts scene as an art critic for Arts Magazine, but still, just being Black and British in New York was enough to keep him toward the fringes. The title of the show alludes to Bowling’s position negotiating these multiple worlds.

Bowling’s “outsider” status is one reason Thüring says he was compelled to include Bowling in a 2019 MFA exhibit on Color Field painting, and why he feels today that a Bowling solo exhibit is long overdue.

“It was really important for me as a statement to talk about institutional history, some of the omissions, but also as a way of redefining and reinterpreting a part of the collection,” he says. “I like this idea of looking back at your own history and looking back at your collection and trying to constantly rethink what we consider the ‘canon’ to be.”

“Frank Bowling’s Americas” traces the development of the artist in the arc of almost 40 paintings. Arriving from London in that period, Bowling brought with him a few yards of canvas imprinted with the image of his mother’s house and variety store in New Amsterdam, Guyana. Those canvases would become the support for several atmospheric paintings made in 1966 incorporating imagery with expansive space and a thread of a narrative.

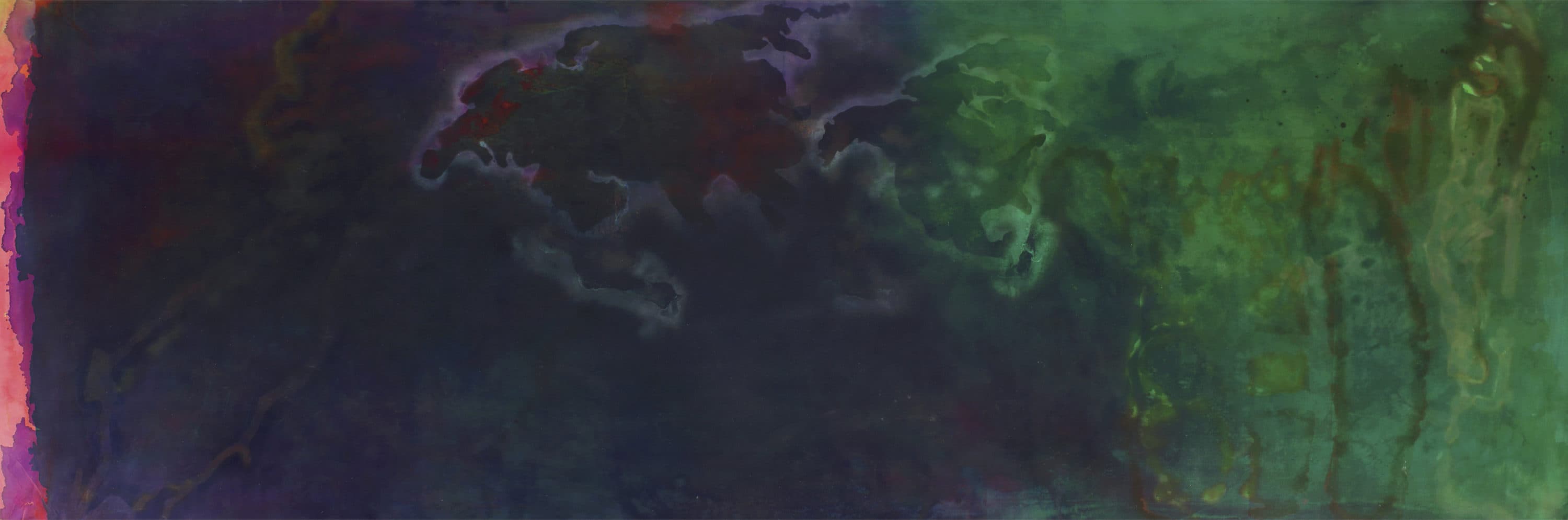

The painting “Untitled (Mother’s House) Old Hag” of 1966, refers to Guyanese folklore. We see outlines of a house and also a faint image in green ink, referencing the mythical Guyanese figure of Ole Higue. A second painting, “Mother’s House and Night Storm,” also features a house combined with the broad fields of color that would come to dominate later canvases.

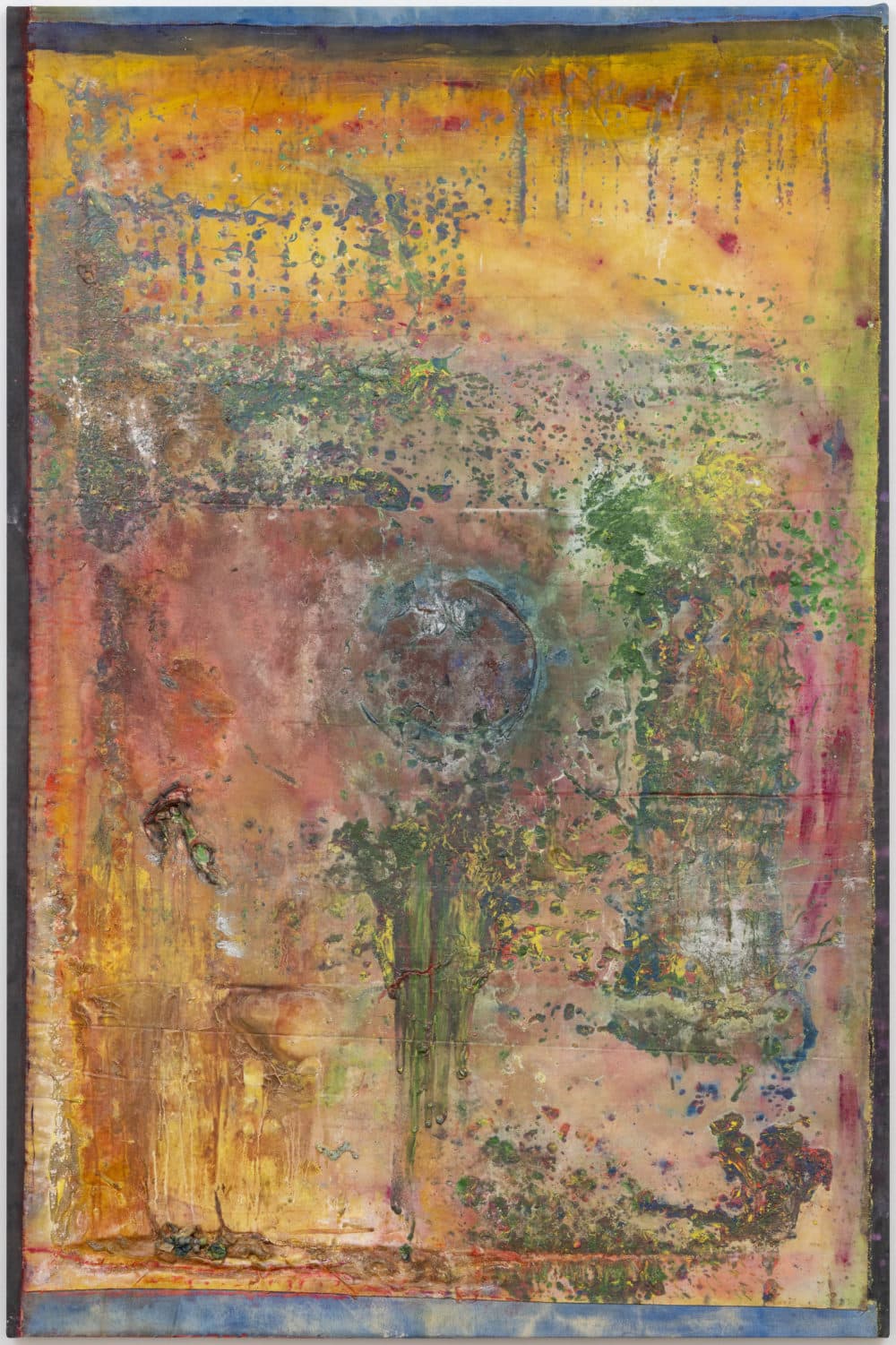

It was not long before abstraction began to have a growing presence in Bowling’s work, although some imagery still remained. Starting in 1968, Bowling created spacious map paintings of almost pure color, with the faint outlines of continents just barely visible. He was already shifting style, using abstraction to consider topics as colonialism, the African diaspora and trans-Atlantic hybridity.

“He does a pretty dramatic shift in style over a rather short period of time,” says Thüring. “And then again, another shift in the mid-70s when he starts to produce works that are fully abstract, where the last remains of figuration basically disappear.”

Around 1973, Bowling began pouring specially prepared, thinned acrylic paint down lengths of canvas. His “Suncrush,” made in 1976, was one of these. While the format of the tall and narrow paintings was not new, it was still a big shift from his earlier expansive map paintings and Color Field works.

All along, Bowling insisted that while his work might hint at social and personal themes, it would never be overtly or explicitly political. Bowling wanted his work considered on its formal merits.

“Black art, like any art, is art,” wrote Bowling while a critic at Arts Magazine. “The difference is that it is done by a special kind of people.”

Still, he seemed to absorb a few tenets proposed by some African American artists at the time, one being the idea, as with AfriCOBRA, of using electric Kool-Aid colors that pop. Many of his canvases, do exactly that, influenced undoubtedly by the colors Bowling would have been surrounded by as a boy in his native Guyana.

Although Bowling was at first not very well-known among his peers in New York, he became well-known. He set up a permanent studio in Brooklyn, wrote, taught at numerous art programs (including at Columbia University and MassArt), and corresponded with art critic Clement Greenberg, whose reviews could make or break an artist.

“I think he very intentionally inserts himself into that context,” says Thüring. “But he comes at this again in this dual role of insider and outsider with a personal history of having moved twice already. And so, it's like this idea of, thinking about Frank Bowling not as an African American artist, but as an artist of color, a Black artist, who really takes that as one of the lenses that he applies to his practice and his painting, but also is absolutely determined to, first and foremost, I would say, be recognized and taken seriously as a painter.”

A criticism could be made of Bowling that, as compelling as his work may be, it might sometimes feel derivative, as if Bowling, immersed in art world trends, may have lost his own unique vision. But Thüring argues that Bowling’s absorption in au courant art styles makes him even more interesting as an artist.

“I consider his work incredibly important and strong,” says Thüring. “It's a bit like his ability to process the history that came before him, to process what was going on around him and then make it his own.”

That’s where Bowling’s uniqueness lies. And it’s about time he’s given credit for it.

“Frank Bowling’s Americas” shows at the MFA from Oct. 22-April 9. Two additional exhibits dedicated to Bowling are being held in conjunction: “Equals 6: A Sum Effect of Frank Bowling’s 5+1” at UMass Boston’s University Hall Gallery Nov. 14-Feb. 18, and “Revisiting 5+1” at the Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Staller Center for the Arts, Stony Brook University, running Nov. 10-March 31.