Advertisement

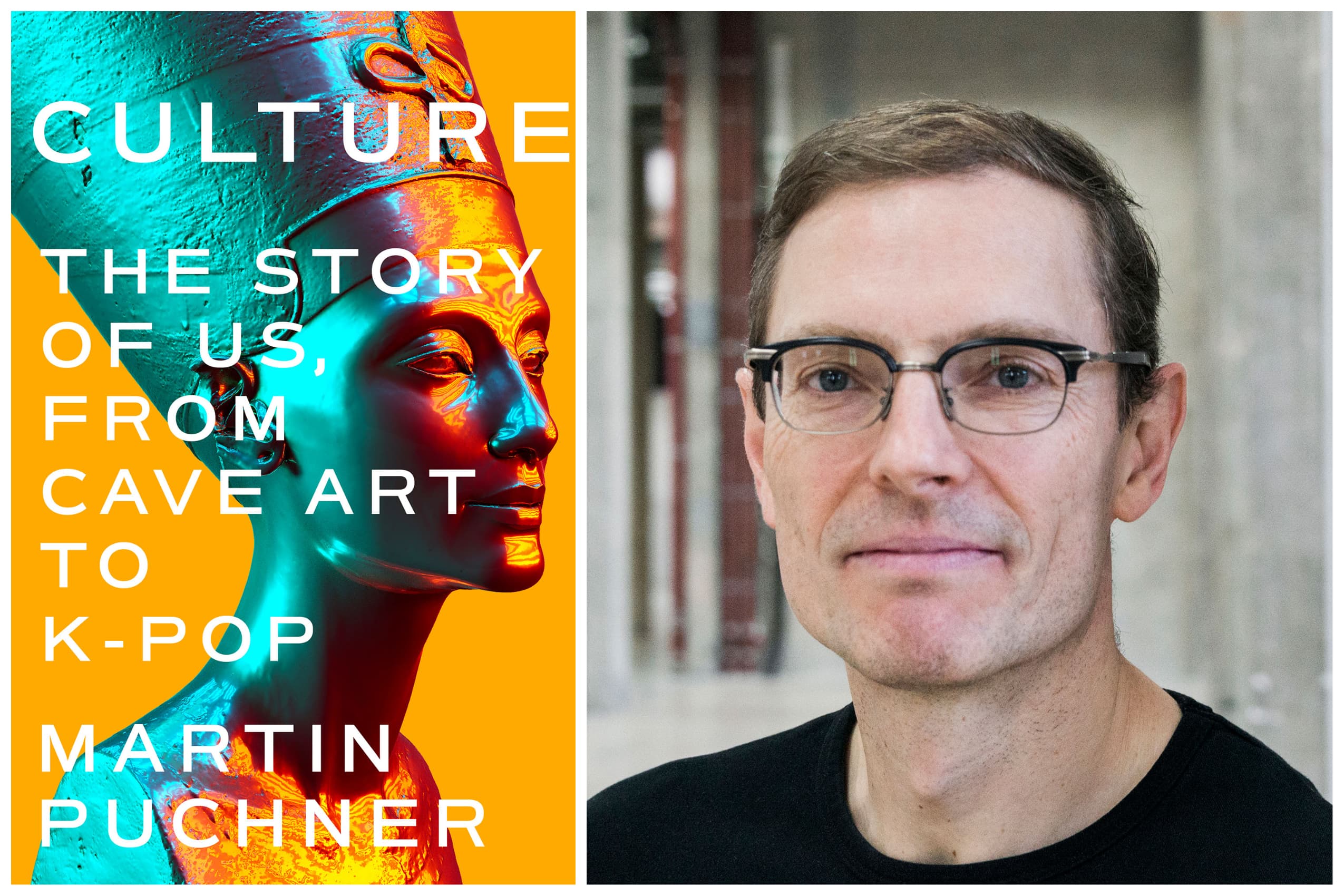

Martin Puchner's 'Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop' is a love letter to the humanities

Since the 2008 financial crisis, enrollments in humanities majors such as English literature, history, and philosophy have fallen precipitously. Students are increasingly seeking more salable skills that they feel might help them get a leg up in the job market and a reasonable return on their ballooning tuition payments. For Martin Puchner, a professor of English and comparative literature at Harvard, the bleak outlook for his field of study led him to a surprising realization.

“I was sitting around the dinner table with friends a few years ago,” says Puchner, “and we were bemoaning this decline in the humanities. But over the course of the conversation, it occurred to me that I didn’t really know if I could explain what the humanities are, or what they’re supposed to be, or why we were doing this at all.” This sent Puchner in search of an answer, one that he hoped would show the value of human curiosity and creativity and make a case for the power of the liberal arts.

The result is “Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop,” a wide-ranging survey of how human culture has evolved over the last 37,000 years or so. To fit this vast timeframe neatly within a single volume, Puchner focuses on 15 moments from various cultures across history that showcase humans engaging in their oldest and most characteristic endeavor—seeking to understand themselves and one another.

Some of these stories offer new perspectives on familiar subjects, such as the adoption of Greek culture by imperial Rome or the clash between European invaders and the Aztec Empire. Others are less well known, but no less fascinating, such as the saga of Ethiopia’s national epic, the Kebra Nagast, which reinterpreted the Hebrew Old Testament in a way that legitimized the country’s medieval rulers and ultimately played a role in the emergence of Jamaican Rastafarianism in the twentieth century.

Throughout the book, Puchner highlights the importance of cultural exchange and the free flow of ideas between various societies, ethnicities and religions, which he believes powered human development through the millennia. “Circulation is how culture survives, and the figures I focus on are agents of cultural mobility,” Puchner says. “For example, Xuanzang, the seventh century Chinese traveler who goes to India to bring back Buddhist manuscripts, or Ennin, the ninth century Japanese traveler who goes to China and brings aspects of Chinese Buddhism to Japan. Their efforts helped Buddhism survive and ultimately become a world philosophy.”

More than just ideas, such figures facilitated the spread of innovations such as written alphabets, paper, and other forms of storing or transmitting information that accelerated the adoption of new cultural and technological developments. Throughout the book, Puchner shows the humanities and technology not merely complementing one another, but thriving together in a symbiotic relationship.

That said, cross-cultural exchanges can also be a source of tension. Puchner writes that they “tend to entangle two cultures in a complicated operation of borrowing and influence, often eliciting anxieties over superiority and dependency.” For Puchner, however, culture isn’t a static object; it’s a process in which claims of ownership, superiority, or originality are moot. “Everything comes from somewhere,” he writes, “is dug up, borrowed, moved, purchased, stolen, recorded, copied, and often misunderstood. What matters much more than where something originally comes from is what we do with it.”

In conversation, Puchner is quick to draw a distinction between what he’s talking about and contemporary concerns about cultural appropriation, which he says he shares. “Obviously, nobody should be picking out a culture at random or making fun of it,” says Puchner, “but we don’t want to throw out the baby of ‘cultural borrowing’ with the bathwater of ‘cultural appropriation.’”

Similarly, Puchner describes the anxiety surrounding the importation or adoption of foreign influences “misplaced,” and says efforts to build walls around a culture to keep it pure or authentic misunderstand what really keeps cultures vital. Contrasting the openness of Al-Ma’mum, the caliph of medieval Baghdad, who sought to collect and intermingle knowledge from far and wide, with the insularity of the Byzantines, he writes that “an inward turn and the closing of intellectual possibilities accompanies and sometimes precipitates decline.”

In “Culture,” Puchner makes a convincing case for all culture being, on some level, a pastiche of different influences that, over time, gains an unwarranted sense of solidity and immutability, largely because we lack the proper understanding of its development. It’s here where Puchner believes the humanities can make a difference. And in today’s world, where different cultures are constantly interacting with one another thanks to mass media, globalization and the internet, we’re likely to see a surge of (and backlash to) cultural syncretism that will increase the need for humanists who can, as Puchner writes, “communicate the significance and excitement of cultural diversity” well into the future.