Advertisement

Review

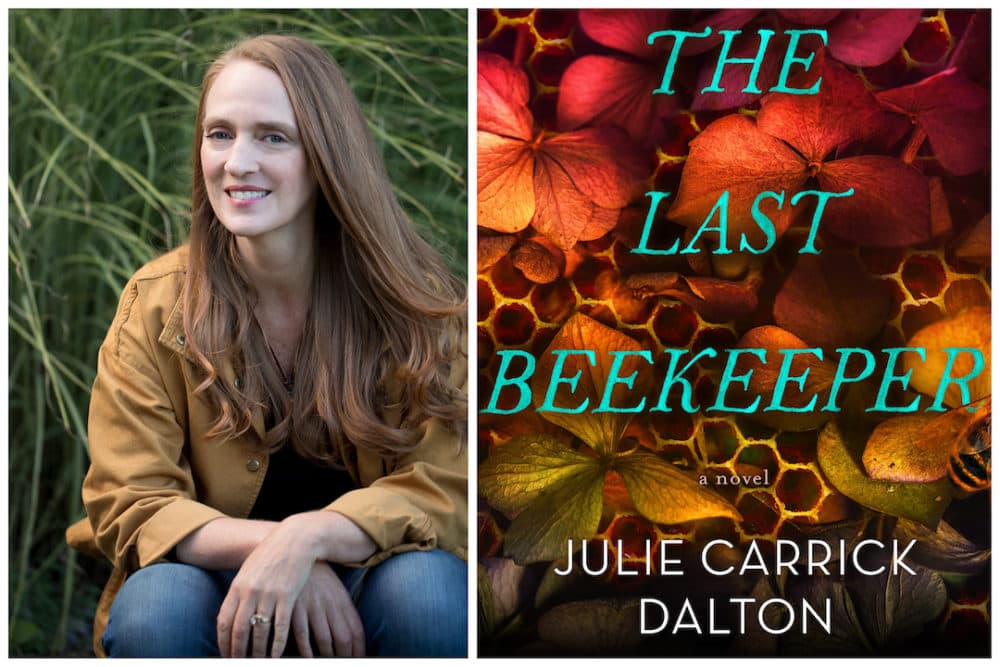

Julie Carrick Dalton's 'The Last Beekeeper' is a hopeful, post-apocalyptic thriller

Julie Carrick Dalton’s “The Last Beekeeper” is many novels in one. An intensely personal mystery wrapped in a post-apocalyptic conspiracy thriller. An alarming yet hopeful reflection on the delicate relationship between humans and nature. A tenderly wrought tale of a young woman’s quest for family and community.

Dalton, who lives in Boston, is the author of the award-winning novel "Waiting for the Night Song.” A former beekeeper who farms land in New Hampshire, she has written for numerous publications on climate change and the art of fiction, including The Boston Globe, Orion Magazine and Dead Darlings.

In “The Last Beekeeper,” it’s a decade after “The Great Collapse,” an environmental catastrophe that killed bees around the globe and consequently decimated the global food supply. Economic and political turmoil soon followed. In the U.S., where the story takes place, unemployment is unprecedentedly high, food is scarce, and the power grid only works in large cities, unreliable.

Yet, in recent months, people in different regions have reported bee sightings. This may seem like a good thing, but the government dismisses these folks as either hysterical or as “troublemakers intent on derailing the precarious food security that had taken a decade to reestablish.” Ominously, those who report a “false” bee sighting soon disappear.

Twenty-two-year-old Sasha, the main protagonist, has journeyed to her rural childhood home after years in the state juvenile care system. She was placed in the system at 12 years old after her father, Lawrence Severn, a scientist and beekeeper, was convicted of keeping bees “outside an authorized facility.” Theirs were the last known bees in North America, and Severn became known as the last beekeeper.

The novel employs two alternating storylines, one in the present and one set in Sasha’s youth, when her world was filled with school and playing her violin, and helping her father tend their gardens and beehives. Each storyline moves forward in time until they merge.

This dual-narrative style has become a popular literary device, yet it can yield mixed results. If one narrative is appreciably weaker than the other, you may suffer through a lopsided, impatient read. Fortunately, that is not the case here. The two storylines build on each other in ways that are equally tense and poignant.

Advertisement

As hive after hive died off, Sasha’s father hid his healthy bees on their land in a building specially designed to protect them from outside contamination and continued his research into the emerging disaster in secret. That is until an accident let the bees loose and led authorities to discover his project.

Severn, viewed as both traitor and martyr, goes to jail rather than divulging his research. Throughout the book, Sasha ponders some large and painful questions. Why did her father choose his research over her? Before his trial, why had he asked her to lie about certain events regarding the bees? Most confusing, why, just before he was taken away, had he whispered to her: “We can rebuild. We are not the last.”

When Sasha reaches her childhood home, she finds squatters have moved in (a common occurrence, with so many abandoned houses on ruined farmland). There’s Halle, Ian and Gino, in their 20s, and Millie, an older woman with a caring, maternal air. Dalton has drawn each with a distinct personality, making for a satisfying variety of conversations and interactions. All have survival stories, which some are more willing than others to share.

After a contentious confrontation, the squatters allow Sasha to stay. She proves her worth with her wide-ranging skills in gardening, cooking and just about any kind of home repair. Sasha finds comfort in everyone’s “squabbles, loyalties, and idiosyncrasies.” She had been searching for a family ever since her own spectacularly imploded.

Sasha’s new friends are aware they’re living in the house of The Last Beekeeper, but they are entirely unaware they’ve welcomed in his daughter. She lives in fear that if they learn her true identity, they’ll toss her out.

Being exiled from her new community would be shattering for many reasons. Sasha returned to her home to find documents she was convinced her father had hidden somewhere on their property. More importantly, Sasha has seen a live bee in the woods near her house.

Dalton allows the tale to unwind slowly and steadily, with daily details that make this ragged reality feel disturbingly authentic. Dalton’s descriptions of woods, flowers and even jars of seeds combine visual beauty with an array of apt emotions, enabling you to see, hear and smell the setting in the time before and the time now.

It's no surprise that “The Last Beekeeper” offers a wealth of minutiae about bees. They hum “at the exact pitch of a G note” on a piano, and a “single bee creates a shadow of the sound a hive makes, a nearly imperceptible hum.” From a young age, Sasha has felt that vibration “like a secret language.”

In ways big and small, Dalton illuminates just how complicated biology is — how altering one aspect of a biosphere can prompt effects that are terrifyingly beyond the planned one. At one point, Sasha muses, “It takes time, but nature always wins.” Interpret that any way you like.

In Dalton’s nuanced writing, there are no individual characters that are wholly good or evil. All the main characters are interestingly flawed, and many have surprising aspects of warmth and humor. Everyone struggles to make the right consequential decisions in a blasted landscape.

As Sasha gathers a ragtag, intrepid group to help her find solutions that might restore their world, she holds something her father once said close to her heart: “Love what exists, what might exist. And fight for it.”