Advertisement

Review

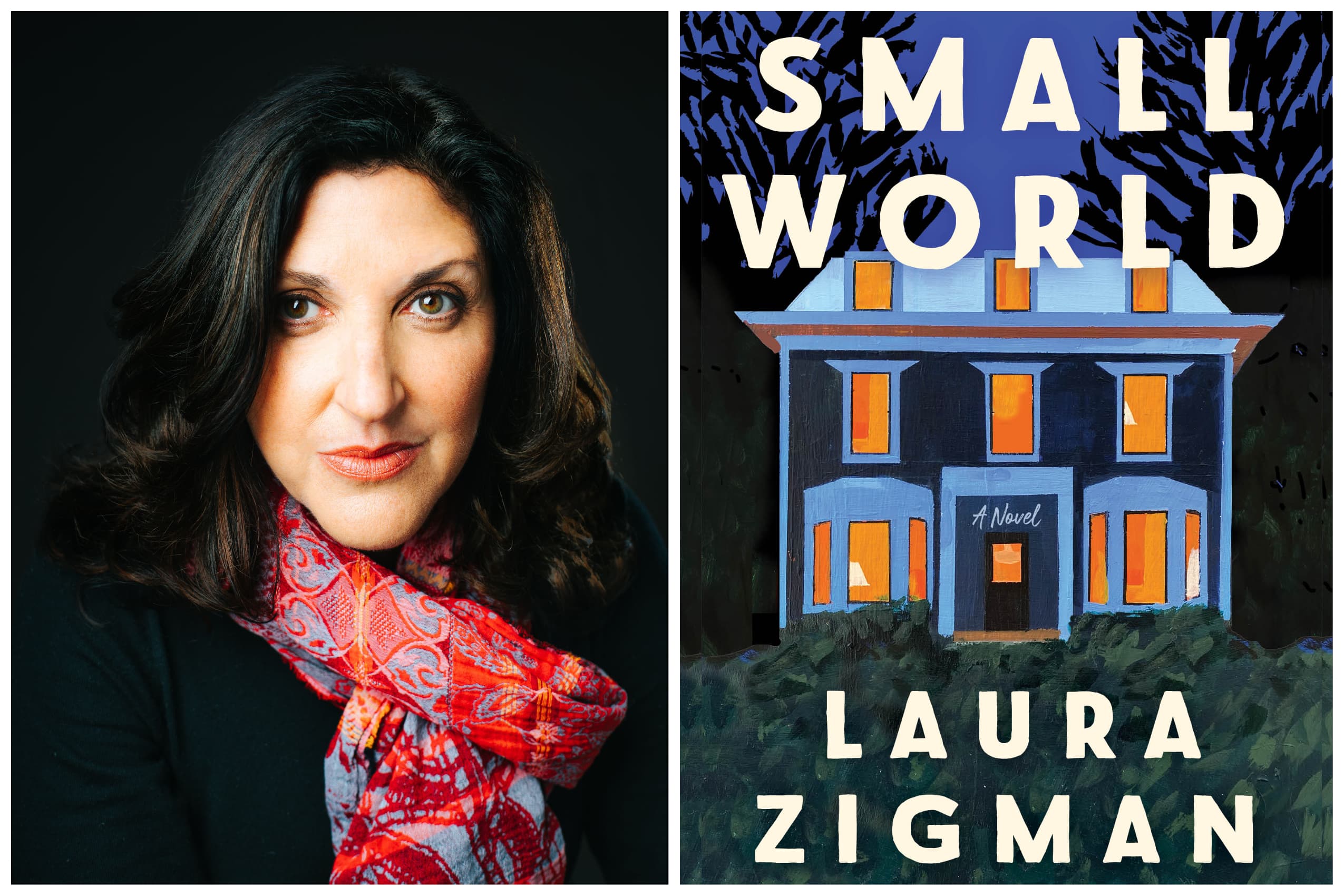

In novel 'Small World,' two adult sisters in Cambridge revisit their troubled childhood

As we head into the messier months of winter, Laura Zigman’s newest novel, “Small World” (out Jan. 10), offers a warming tonic against ice and gloom.

Zigman, a Newton native and UMass Amherst alum, is the author of five previous novels. These include the 1998 bestseller “Animal Husbandry” (the basis for the 2001 movie “Someone Like You”), and the 2020 “Separation Anxiety,” which has been optioned by Julianne Nicholson ("Mare of Easttown") for a limited TV series. As in her earlier work, “Small World” is an appealing blend of depth and froth.

After decades apart, two sisters, Joyce and Lydia, try to forge a new understanding about the difficult childhood they shared and the sister that they lost. Both are recently divorced and on their own, and Joyce has invited Lydia to stay at her Cambridge apartment while Lydia looks for a new home. Joyce, whose voice carries “Small World,” hopes they’ll establish a closeness they’ve historically lacked; she also knows her older sister’s barbed personality may still hinder that.

Though set in the present day, Zigman seamlessly weaves in many of Joyce’s childhood memories, and distinguishes these by an elegant shift in tone. In the main story, events and conversations move along at a lively pace. When Joyce recounts something from her family’s past, she does so in a dream-like second-person present tense; the kind of voice you might use when talking to yourself, remembering and reconsidering a memory.

The middle sister, Eleanor, was born with cerebral palsy; she died at just ten years old. Joyce and Lydia had loved Eleanor, yet it was a complicated love, flecked with awkwardness and resentment. In public, the young girls were all too aware of Eleanor’s “yellow teeth, the drool, the sounds she makes… the smell …when she needs to be changed.” Most of all, they resented how Eleanor seemed the only daughter that mattered to their parents, especially to their mother.

Zigman writes insightfully of the agonizing push-pull of a family raising a child with severe needs, especially in the 1970s when the choices were often home care with little help or institutions with few resources.

During Eleanor’s lifetime, their mother, Louise, became a fierce advocate for the rights of those with developmental disabilities, a whirlwind of caring for Eleanor and hosting fundraising and activist meetings. After Eleanor’s death, Louise devoted even more energy to the cause, lobbying Congress and meeting with governors and senators.

And yet, any issues that Joyce or Lydia faced — dyslexia, a stutter — were considered too minor to be acknowledged, never mind addressed. With compassion, as well as blunt appraisals, Zigman shows what it was like to grow up in a home that was emotionally tilted and ultimately wreathed in sorrow. Lydia developed an outsized, drama-filled personality; Joyce cultivated a stoic demeanor, to the point of becoming nearly invisible.

Joyce lives just outside of Harvard Square, and the inclusion of local establishments like Cardullo’s, Harvard Book Store and Grendel’s Den makes the story nicely Cambridge-centric, as does Zigman’s often-comic portrayal of Joyce’s neighbors and their concerns. Few writers do Cambridge sendups better than Zigman; she not only knows the cultural terrain well enough to hilariously mock it, but does it in a way that shows how even residents who roll their eyes at local concerns (like what makes an acceptable Halloween treat) would not live anywhere else. The humor here is less persistent than in “Separation Anxiety,” but no less smartly done.

The book’s title has multiple meanings. It’s the name of a neighborhood website to exchange goods, services and information. Joyce loves how Small World solves little problems; she keeps a journal of poems she makes from its postings, “a form of silent meditation.” The poems are basically messages reformatted with poetic line breaks, yet her choices elevate each query or complaint into something much more, revealing hidden yearnings, joy or self-righteous anger underneath the words. The poems are scattered throughout the book, offering thoughtful grace notes to the story.

“Small World” could also refer to Joyce’s own world, expanded now with Lydia as roommate, and possibly upended by a new couple who have moved into the apartment above hers. They are running a noisy, and probably illegal, wellness studio from their home. The intra-house conflict that ensues provides an amusing counterpoint to Joyce and Lydia’s sometimes-contentious relationship. Joyce cannot understand why Lydia is so short-tempered when Joyce brings up anything from their family; Lydia considers Joyce obsessed with the past.

Lydia is not wrong. Joyce will admit, only to herself, that she’s stuck in a melancholy gear. It’s no accident that for work, Joyce is an archivist at a company that transforms family photos into digitized highlight reels, a job that allows her to indulge her curiosity about other families — the colorful birthday parties and adventurous vacations and graduations packed with adoring relatives — and consider “how their parts fit together… or don’t.”

As the weeks and then months of ordinary life glide by, the sisters’ shared activities begin to wear down the rough edges between them. Some random yet believable encounters with old family friends shed some surprising light on their past, which may allow the sisters to see each other in a better, more understanding light.

The book’s short, powerful epigraph is “I came to explore the wreck.” – a line from Adrienne Rich’s “Diving into the Wreck.” Choosing to enter an ancient vessel that has been deeply buried for years takes some courage — kind of like Joyce and Lydia bravely exploring their own history — for which other lines from Rich’s poem could apply: “the thing I came for:/ the wreck and not the story of the wreck/ the thing itself and not the myth.”