Advertisement

Review

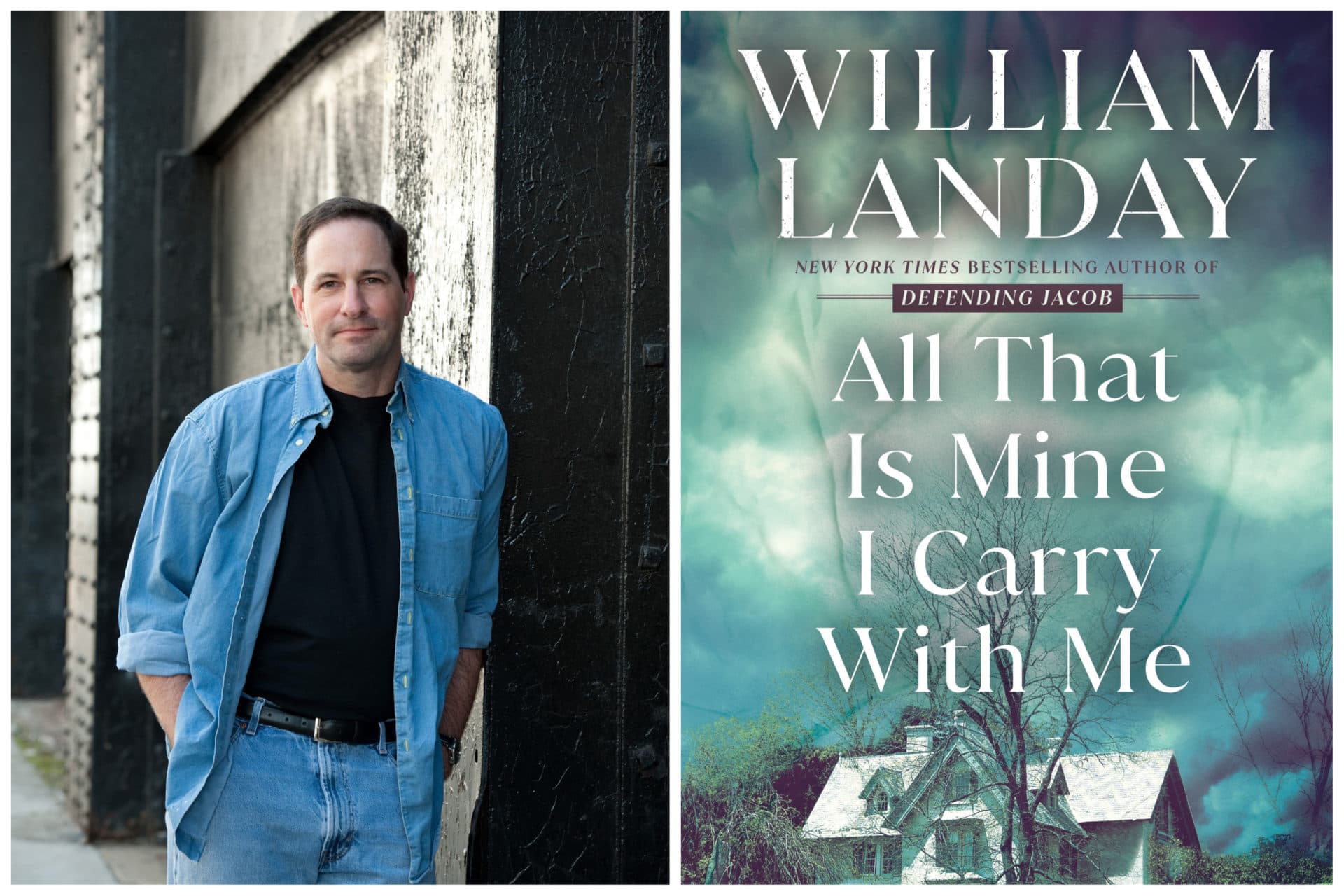

'All That Is Mine I Carry With Me' is an uneven but haunting whodunit based in Newton

On an ordinary weekday in November of 1975, Jane Larkin – age 39, wife of Dan, mother to Alex, Jeff and Miranda – vanished from her Newton home.

William Landay’s uneven but haunting whodunit, “All That Is Mine I Carry With Me” (out March 7), illustrates how this overwhelming loss reshaped the lives of each member of Jane’s family. In doing so, Landay also underscores the perilous power of the stories we choose to tell ourselves about those we love.

Landay, a former assistant district attorney, is the author of the best-selling “Defending Jacob” (made into a 2020 Apple TV+ series), as well as the award-winning novels “The Strangler” and "Misson Flats." He lives in Boston, and the storylines in this novel are bolstered with evocative details of Boston, Cambridge, Newton and Brookline.

“All That Is Mine I Carry With Me” does not begin on the day of Jane’s disappearance, but in the near present, with a focus on Philip, an old school friend of Jeff’s and a novelist of some success.

Beginning the book at a slant signals a storytelling style that will not be rushed and may not proceed in a linear fashion. Philip has been feeling creatively “empty,” so he’s interested when Jeff contacts him about penning – not a true crime book – but a novel based on his family’s ordeal. For a writer, Philip speaks in a maddeningly meandering style, constantly interrupting his recollections of Jane’s disappearance with tedious personal asides.

Philip’s is the first of four large sections, each told from a different character’s point of view. The overlapping and sometimes-conflicting perspectives move the tale forward from the 1970s into the 2000s. Issuing a telling warning on the reliability of anything you’re about to read, Philip notes “I do not trust my own memories. I tell myself so many stories about my past, as we all do.”

Jane’s disappearance touches off a wide-ranging criminal investigation and a multi-year search. Her photo is featured in newspapers and on national TV news, the coverage prolonged in part by her beauty, the upscale town where her family resides and her marriage to a prominent attorney. Tom Glover, the lead detective, remembers that her case “never really went away;” people across the country frequently thought they saw her.

Advertisement

With everyday details, Landay reveals significant differences between a missing-person case then and now. A first question the Newton police consider: Is Jane’s disappearance a crime, or an escape?

In 1975, the second wave of feminism was cresting; it was plausible that a middle-class mother, even an apparently contented one, could leave her family for an entirely different life. The 1970s was also a world unencumbered by Google, cell phone towers, or national driver’s license databases. As one character muses, “It was easier to disappear then.”

Sadly, there is one stark similarity between a missing-person case then and now. A white woman who goes missing will still garner exponentially more media attention than a missing woman of color. (Some current works of fiction reflect this real-life disparity. The ABC TV show “Alaska Daily” delves into the disturbing number of indigenous women who go missing, with scant official effort to find them. Lisa Gardner’s most recent mystery series features amateur sleuth Frankie Elkin, who searches for people whom the police have given up on and the media have ignored.)

No matter the circumstances, a missing person story carries a dread-filled aura. A loved one was there, and then gone; plucked out of ordinary life by an unseen monster. Those who remain must continue their lives in a world where everything has changed but everything looks the same. Miranda, the youngest child, remembers “It was like living in this in-between state. We kept imagining she would walk in at any moment.”

But – What if the monster lives in your house?

Though there is no hard evidence against him, Dan is a prime suspect, and not just because he’s the spouse. Professionally successful and personally fastidious, he plays the part of a grieving husband almost too well. He’s not wrong to grumble that he can’t defend himself against rumors, yet, some of his behavior invites speculation.

At a dinner with Jane’s sister and her husband a year or two before Jane disappeared, Dan had confidently proclaimed “all married men are a little unhappy, secretly, at least the ones who marry young.” That was not a comment his sister-in-law would forget, especially since she’d considered Dan a self-absorbed peacock ever since he and her sister were sweethearts at Brookline High School.

In 1993, Jane’s body is found hundreds of miles north in New Hampshire. This is hardly the end of the story. Instead of bringing closure, the discovery raises even more confusing questions, and triggers a dramatic decision by some of the siblings that threaten to open even deeper rifts within the family.

The novel’s strongest feature is the evolving portraits of each member of this household, and how their ongoing nightmare scraped at the siblings’ bonds with each other and with their father. From that fateful day on, there were no neutral actions. Was fully answering a police question a betrayal of their father? Was enjoying a school event a betrayal of their mother?

Alex, the high school star who would become an affluent attorney, had always been indifferent to any developments in their mother’s case. Automatically accepting his father’s innocence enabled Alex to draw a protective shield around his own ambitions.

Jeff, who’d already had a fractious relationship with Dan, is convinced from the start that his father was a murderer. Jeff’s unending, helpless rage seems to slowly collapse him from the inside out. He drifts into adulthood on a stream of short-term jobs and longer-term drug habits.

The book’s title, “All That is Mine I Carry with Me,” is a translation of the maxim “Omnia mea mecum porto,” meaning your most important possessions are your character and your wisdom. Miranda, who has spent her life trying to make peace with her mother’s fate, has the quote in Latin tattooed on her inner arm. An artist who’s battled bouts of depression since her mother’s disappearance, Miranda has more hidden reservoirs of strength than either of her brothers.

But even Miranda’s scenes, which carry the most depth, do not provide enough cohesive complexity to make this a satisfying saga. Reaching the final pages, I still waited for an ending – whether expected, shocking or tantalizingly undetermined – that would have truly built on all that came before.