Advertisement

Mass. firefighters and their families are on the front lines of a battle with 'forever chemicals'

It looks like a knitting room, with wicker baskets and soft yarns. But Diane Cotter calls it her war room.

“This is where the research is done and the strategies come into fruition,” she said, looking around the small room off her kitchen. “There was a long time that I wasn't knitting because I was so immersed in the war.”

Cotter’s war started late one night in 2014.

Her husband, a longtime firefighter in Worcester, had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. Complications from the treatment forced him to give up his career as a firefighter. Soon depression set in.

“While he was sitting in a reclining chair, slipping further and further away, I began researching," she said. She typed "firefighter cancer" into her browser.

Staying up late, night after night, Cotter searched for clues about whether something about her husband’s work could have caused his cancer. After a conversation with environmental activist Erin Brockovich, she zeroed in on PFAS chemicals.

PFAS, which stands for per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of chemicals invented in the 1930s. They are used widely because they are good at making surfaces repel water, oil and grease. These chemicals are infused into the protective clothing firefighters wear.

Although it's unclear whether they caused her husband's illness, some PFAS chemicals have been linked to health concerns, including kidney cancer and testicular cancer. Nearly a decade later, Cotter has played a significant role in spurring scientists, firefighters and politicians to reckon with the presence of PFAS in firefighters' gear.

PFAS chemicals were also used historically in some firefighting foams, and they continue to be used in a broad range of consumer products, including non-stick pots and pans, dental floss and toilet paper. Chemical companies say some types of PFAS are safe. But scientists remain concerned by the way these substances accumulate in people's bodies and the environment.

As the public begins to grapple with how to address these chemicals, a number of Massachusetts firefighters and their families find themselves at the forefront of this fight. They’ve raised awareness about PFAS not just in firehouses, but also in statehouses and courthouses.

“It’s a canary in the coal mine situation,” said Courtney Carignan, an exposure scientist at Michigan State University who studies PFAS. “The firefighting community has a very strong interest in these issues because their exposure to PFAS and other chemicals is so much higher than the general population.”

'It was mind boggling'

When Cotter first asked manufacturers whether PFAS were in firefighters' protective clothing — often called turnout gear or bunker gear — the companies wouldn't tell her, she said. So she came up with a strategy: “emailing everybody I could think of.”

“I got one of the 6,000 emails she sent,” recalled Graham Peaslee, a physics professor at the University of Notre Dame, who studies PFAS.

He clicked reply. “I’d be happy to test it,” he remembered typing. “Do you have a piece of a sample you can send me?”

Cotter didn’t. So, she started selling sweatshirts, and organizing yard sales and cake sales to raise enough money to buy one. With help from a foundation, she got the gear and sent a sample to Peaslee. He ran the tests.

“It was mind boggling,” he said. “It took me a year to believe the result that we had because nobody had ever said that or published it.”

Peaslee said the PFAS in the samples were “higher than anything else I had seen” except pure Teflon, one of the first widespread uses of PFAS. He was even more alarmed to see how readily the chemicals came off the gear and onto the gloves used in his laboratory. He worried these chemicals “were capable of being a significant exposure risk to the firefighters.”

Advertisement

“We deserve better as firefighters, and quite frankly the public deserves better. When we go out the door to a call, we're coming into your homes. It's flaking off us and flowing around your house.”

Edward Kelly

Peaslee got other scientists to run similar tests, and they confirmed his findings. Now, it’s an active area of research.

Carignan, of Michigan State University, found that firefighters had elevated PFAS blood levels even if they had little to no exposure to firefighting foams that contained PFAS. On average, these firefighters’ levels were two times higher than the general population. While that’s concerning, she said, she’d classify it as only “moderately” elevated when compared with other highly-exposed groups, like people who work in PFAS manufacturing plants.

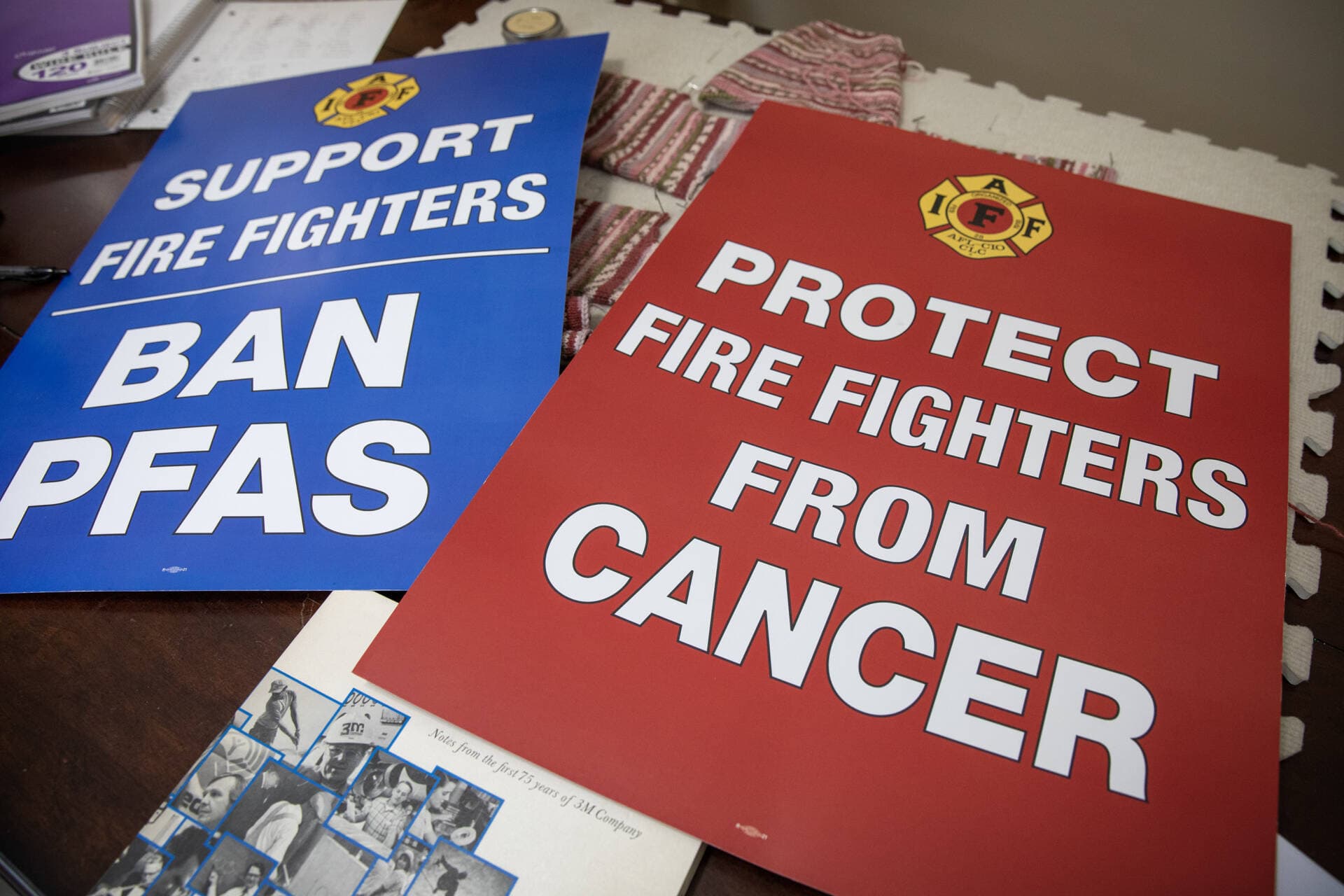

As news of the studies trickled out, the findings became a wake up call for many firefighters. The largest firefighters union in the country, the International Association of Fire Fighters, decided to take on the issue.

Taking PFAS to court

“As firefighters, we know we have a dangerous job,” said Edward Kelly, a Boston firefighter and head of the union. “What we didn't realize until recently is that our personal protective equipment, our PPE, our bunker gear is manufactured with PFAS toxic carcinogenic chemicals infused into it.”

This realization, along with failed efforts to remove those chemicals from gear, brought Kelly to the lawn outside Norfolk County Superior Court in Dedham in March. He was there to file a lawsuit against the National Fire Protection Association, a Quincy-based nonprofit that sets the standards for firefighter gear.

The union alleges the guidelines essentially require all firefighter gear to contain PFAS. The lawsuit also accuses the group of colluding with manufacturers to keep it that way.

“We deserve better as firefighters, and quite frankly the public deserves better,” Kelly told reporters at the courthouse. “When we go out the door to a call, we're coming into your homes. It's flaking off us and flowing around your house.”

The National Fire Protection Association denies the allegations. The group declined interview requests but said, in a statement, that the lawsuit is “meritless.” It called the union’s accusations “false and defamatory.”

Gore, one of the gear manufacturers, also declined interview requests. In a statement, the company said it “is confident in the safety” of its gear. Gore maintains that the type of PFAS used in its gear, called PTFE, is non-toxic and does not put firefighters' health at risk.

The company’s website says PTFE molecules are too large to enter human cells and lack the chemical properties to move into cells by interacting with other types of molecules.

“We were hypersensitive to the issue of PFAS exposure because we were working with the product every single day,” said Seth Harper, a former employee of Gore.

But Peaslee of Notre Dame questions the assertion the PTFE is the only PFAS chemical present in firefighters' gear.

The union's lawsuit is one of a number of recent legal challenges involving firefighting equipment and PFAS.

In 2022, Cotter's husband — Paul Cotter — joined other Massachusetts firefighters diagnosed with cancer in a federal lawsuit. They accused more than two dozen companies that either manufactured or used PFAS in firefighting equipment of causing their illnesses and deceiving them about the risks.

Also in 2022, Gov. Maura Healey, who was then Massachusetts' attorney general, sued 13 PFAS manufacturers that made firefighting foams accusing them of contaminating drinking water and other natural resources.

In the firehouse

The union's lawsuit and a steady stream of PFAS studies have prompted some firefighters to debate PFAS and how to treat their turnout gear.

Kelly urges firefighters to use their gear only when absolutely necessary. He’s concerned that near-daily PFAS exposure is contributing to a high cancer rate among active duty firefighters.

“The number one killer of firefighters is cancer,” Kelly said. “About 75% of the names we put on our wall are dead from job-related cancer.”

“It’s a canary in the coal mine situation. The firefighting community has a very strong interest in these issues because their exposure to PFAS and other chemicals is so much higher than the general population.”

Courtney Carignan

Research by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found firefighters' die of cancer more often than the general U.S. population. Instead of blaming PFAS, Harper — the former Gore employee — points to another cause.

“What we find today is that fires are burning hotter, faster and more carcinogenic than they have ever before,” he said.

Modern products and building materials can be more dangerous than materials used in past decades. It can be unhealthy to breathe in the soot and particulates created when these materials combust, but it’s also a problem when they build up on the skin. Harper argues wearing firefighting gear is one of the best defenses.

“If we warn people about PFAS in gear and that causes them to reduce the amount of protective gear that they are wearing,” he said, “I think that that could be two steps backwards.”

Kelly readily admits that firefighters' are exposed to a lot of carcinogens at work, like burning plastic. But he sees that as a known risk, and one that's long been part of the job. PFAS in their gear, he worries, is an added — and unnecessary — exposure.

Carignan, at Michigan State, has noticed the toxic brew of chemicals is taking a toll. “Deaths used to occur post-retirement,” she said. “Now firefighters are getting cancer and dying in their 30s, in their 40s. They're not even getting to retirement.”

She said recent interventions to reduce firefighters' exposure have focused on things like idling firetrucks, smoke inhalation and transitioning away from PFAS in firefighting foams. Kelly would like to see changes in gear added to that list.

Traditionally, many firefighters have worn their gear while working out or hanging around the fire house. Often they wear the full protective suit to each call, even though many are false alarms. Gear also is a source of pride and is worn regularly to ceremonial events. While the union is trying to change those practices, it hasn’t been easy.

“I think some fire chiefs have been slow to step up to their responsibility and limit their own firefighters' exposure to this,” said Kelly.

Firefighters face many potential exposures to PFAS outside of their gear, from smoke inhalation to drinking water. Some firefighters expressed skepticism about the risks of wearing their gear, and said they're concerned that making firefighters afraid of the gear might put them in even greater danger.

“Despite years of research into potential alternatives, which is ongoing, PFAS-based materials are the only viable options for effective firefighting gear that meets the National Fire Protection Association’s protective gear performance requirements,” the American Chemistry Council said in a statement. The group, which represents chemical manufacturers, declined an interview request.

Nate Barber, a firefighter in Nantucket, avoids touching his gear as much as possible. He said he typically tries to touch it just once during each shift and then he washes his hands. He first learned about PFAS after he was diagnosed with testicular cancer and discovered he has above-average levels of PFAS in his blood. However, he said, some fire departments label people as weak if they worry about PFAS exposure.

“You have these macho firefighters — like instructors in the academy — saying, ‘You need to wear your gear,’ ” Barber said. “The fire service hasn't come to grips with the fact that they're being exposed. It’s crazy.”

Barber's wife, Ayesha Khan, created the Nantucket PFAS Action Group to try and raise awareness about PFAS in the fire department and the community.

At the Massachusetts State House

It was the firefighter cancer rates that struck state Rep. Kate Hogan, a Democrat from Stow. She found the numbers “surprisingly and shockingly” high.

Hogan is one of the lawmakers who introduced a sweeping PFAS bill on Beacon Hill. One part of the bill would require PFAS chemicals to be labeled in firefighter gear and, eventually, phased out. It would also require the state’s Department of Public Health to collect and report data related to PFAS exposure on the job.

Hogan would like to see more public awareness campaigns related to PFAS.

“It's really important that firefighters know there's PFAS in their gear, and they know that there's PFAS in their foams,” she said.

From the computer in her war room, Diane Cotter said she’s noticed more firefighters taking note of the issue and sharing their stories.

“You look at my Facebook page, all day long you're going to see 35-year-old firefighters, 40-year-old firefighters with testicular cancer or kidney cancer,” she said. “This was so unnecessary.”

Cotter said her focus now is on the next generation of firefighters, and finding a way to reduce their exposure to PFAS.

WBUR's Barbara Moran contributed reporting to this story.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to reflect that Edward Kelly is currently a Boston firefighter and to include comments from a former Gore employee who spoke after the piece was initially published.

This article was originally published on April 18, 2023.

This segment aired on April 18, 2023.