Advertisement

After long, steep decline, the North Atlantic right whale population appears to stabilize

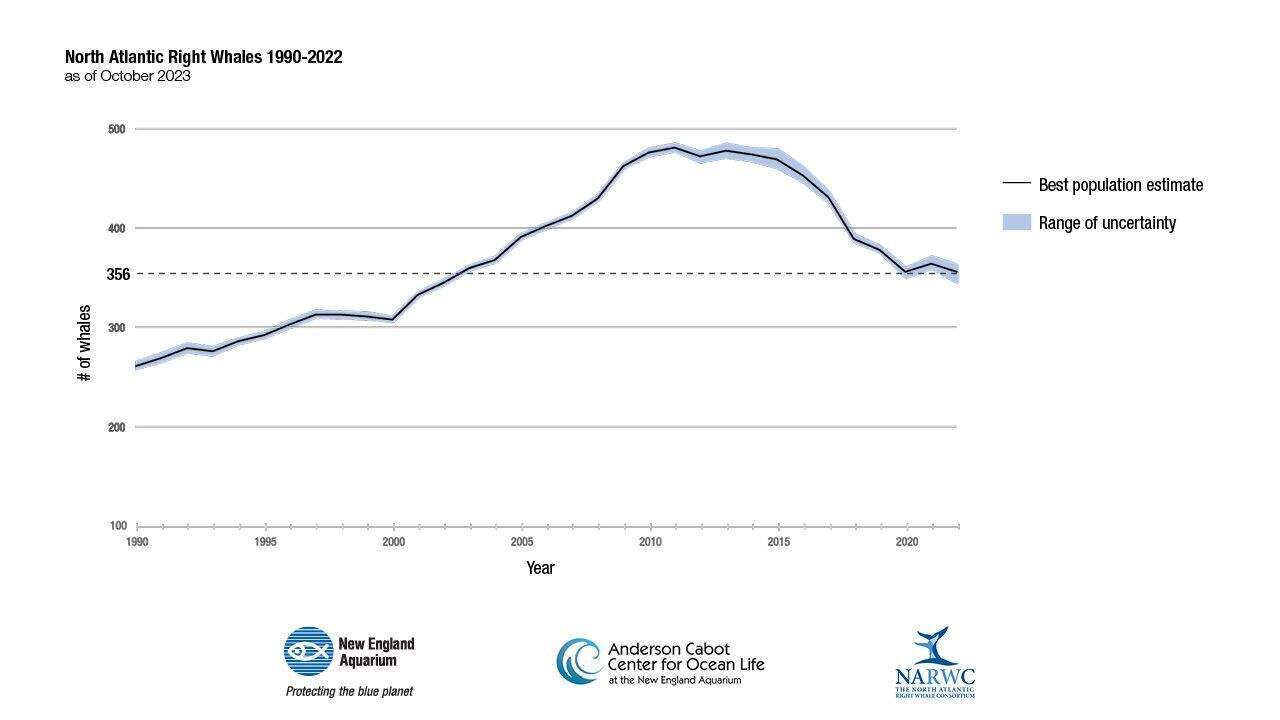

There are about 356 North Atlantic right whales left in the world, according to data released Monday from the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium. That's actually a bit of good news for the critically endangered species, signaling that the population may be starting to stabilize.

"After years of the population trajectory in being in steep decline, that decline is leveling out," said Philip Hamilton, a senior scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium. Hamilton said he wouldn't quite frame the population numbers as "optimistic," though: "I guess I could say it eases the weight on my heart a little bit, but we have a long ways to go."

Right whales still face significant threats. The leading causes of death and injury to right whales are entanglements in fishing gear and getting hit by boats; climate change and noise pollution are added stressors.

So far this year, researchers from the New England Aquarium have counted 32 injuries to right whales after they were hit by boats or entangled in fishing gear. There have also been two detected deaths of right whales in 2023: a 20-year-old male struck and killed by a boat and an orphaned newborn calf.

"Not only are human activities leading to the deaths of whales, but they're also leading to these injuries that aren't outright killing the whale, but they're stunting their growth. They're delaying reproduction in females," said Heather Pettis, a research scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium. She said the whale population can only recover if their birth rates go up, while their death rates go down.

"If we reduce those human impacts, we not only prevent the mortalities, but we also prevent those injuries to allow the right whales to reproduce."

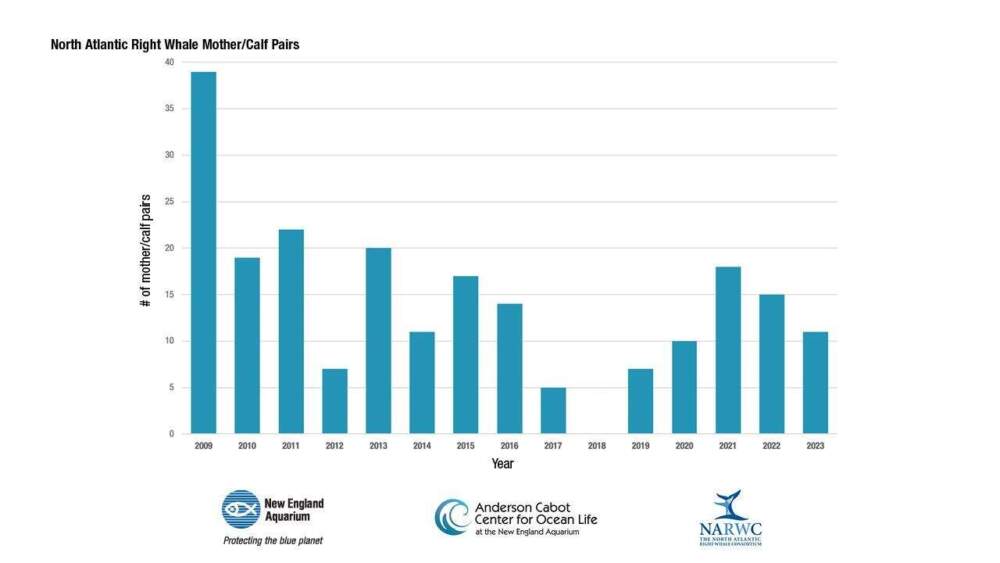

Female right whales can start giving birth as young as 5 or 6, said Pettis, and can have a calf every three to four years. But recently, female right whales — stressed by injury and a shifting food supply — have been giving birth later and to fewer calves. Only 11 calves were born in this year's calving season — fewer than in the previous two years (18 in 2021, and 15 in 2022). A 10-year-old whale named Pilgrim was the only first-time mom in this year's group.

"There are a lot of ways these injuries can impact a female's ability to get pregnant, carry a pregnancy and support a calf," said Pettis. A whale entangled in fishing gear won't be able to feed well, for instance. "And if you're not able to feed effectively, that will impact your energy stores. The process of healing is going to impact reproduction; the increase in stress hormones as a result of injury will impact reproduction."

To help protect the right whales, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) established both mandatory and voluntary slow zones along the east coast for boats 65 feet or longer. A March 2023 report from the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary found high compliance with these regulations off the coast of Cape Cod.

However, a more recent report from the environmental advocacy group Oceana, which used a stricter standard of measurement across a wider area of ocean, found that 84% of these boats violated speed limits in mandatory slow zones, and 82% of boats sped in voluntary slow zones.

"Enforcement needs to be improved," said Gib Brogan, a campaign director at Oceana. "The government needs more resources and more tools to enforce these regulations and make sure that we're at or near 100% compliance. The whales need that level of protection so they can safely migrate."

NOAA proposed tougher regulations on boat speeds earlier this year, a move that has drawn praise from environmental groups and criticism from recreational boaters and fishermen. Final regulations are expected by the end of this year. There have also been calls for commercial fishing boats to adopt ropeless gear, a proposal that faces pushback on cultural, financial and practical grounds.

Beth Casoni, executive director of the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association, said additional restrictions on the state's lobster industry would be unfair.

“The Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association is constantly seeking ways to better identify where these unfortunate interactions are happening," wrote Casoni in a statement. She said the state's lobster industry already obeys "the most draconian conservation rules," which close more than 11,000-square miles to fishing when the whales are present.

"This affords them to come into our waters and freely feed with a 0% chance of an interaction happening with fishing gear. One state alone cannot save this species.”

In September, NOAA received roughly $82 million from the Inflation Reduction Act to help monitor and protect right whales. The funds will expand monitoring of the species along the east coast, help develop a satellite tagging program, help prevent boat strikes, and encourage fishermen to try whale-safe gear.