Advertisement

Boston's Weekly Health Newsletter

From Paxlovid to Spikevax: Inside the 'intensive' process of naming drugs

Editor's Note: This is an excerpt from WBUR's weekly health newsletter, CommonHealth. If you like what you read and want it in your inbox, sign up here.

Scott Piergrossi’s informal motto is “you name it, we name it.” Yes, you read that correctly. He is the “chief namer” at the Brand Institute, a branding agency.

His team helps dream up names for more than 75% of all new drugs approved worldwide each year. That includes more than 2,000 brand name drugs, plus some 1,600 generic, or “nonproprietary,” drugs.

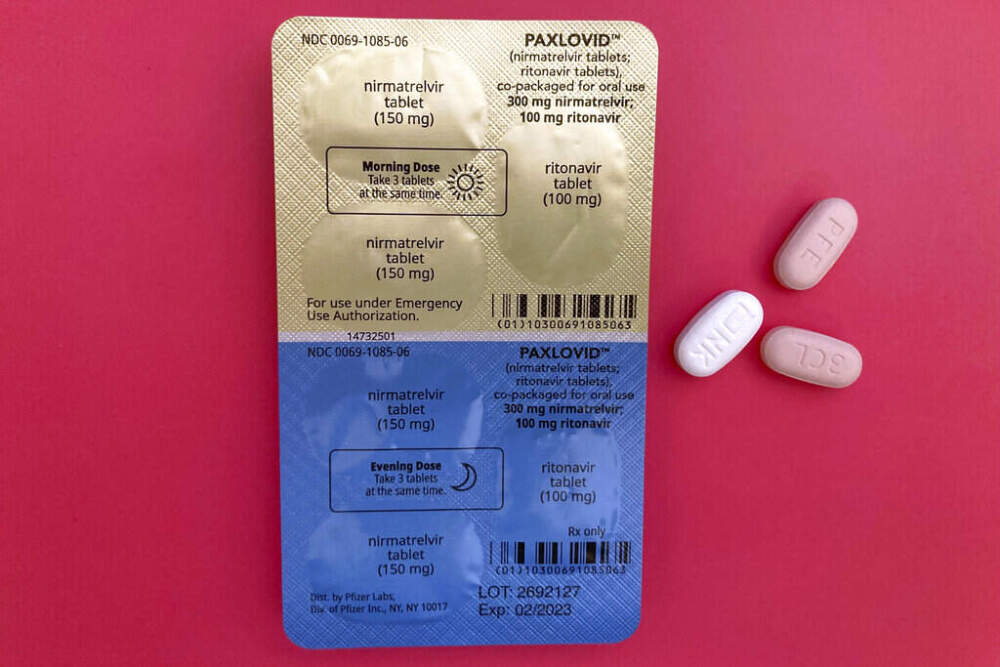

Some you’ve probably heard of, like Pfizer’s Paxlovid, and Spikevax, the name for Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine. Piergrossi is aware some of these names can be perceived as an afterthought.

“The typical reaction to a pharmaceutical name is like, ‘Who came up with that? They must have shouted it out when they were leaving a meeting,’ ” he said. “But no. It is so intensive and so robust.”

That’s partly because this job comes with an unusual wrinkle.

“It’s the only product in the world that requires government approval of the name to go to market,” he said.

I wanted to know more about the drug naming process, so I caught up with Piergrossi. Here are some of the highlights from what I learned.

What’s in a (generic) name?

There are two gatekeepers for generic drug names: a group within the American Medical Association and a group inside the World Health Organization. For both, the process is pretty rigid.

The names must contain two parts. One is a stem that says something about what the drug does. For example, “-vir” indicates an antiviral, and “-estr” tells you there’s an estrogen containing compound in the medication. The other part is a prefix, and that’s where a manufacturer — often with the help of someone like Piergrossi — can play around. But as Piergrossi told me, there are still rules.

“You can’t reference the manufacturer’s name. You can’t have anything that can be perceived as a claim or overly promotional. There are certain letters you can’t use because of pronunciation in different languages,” he said. So, Y, H, K, J, and W are banned.

Playing the brand name game

Brand name drugs are overseen by a different public health agency in each country. In the U.S., it’s the Food and Drug Administration. The goal is to land on one globally recognized name, so even though all the letters are allowed here, Piergrossi’s team still avoids many of the letters outlawed in the generic process.

When coming up with a brand name, Piergrossi said his team starts by asking what the manufacturer wants it to suggest, represent or sound like. Then, the team comes up with 2,500 potential names (he said he can come up with 600 in less than three hours).

Next, they whittle down the list to 100, then 20 and eventually, just six to eight name recommendations. There are lots of steps in the process, from assessing “trademark-ability,” to important questions about whether a name is too similar to other drug names and might cause medication mix ups. And of course, there’s plenty of market research to be done, which varies based on whether the name is meant to appeal to physicians or patients.

‘A blank canvas’

Piergrossi couldn’t say much about specific drug names and where they came from since he didn’t want to step on his clients’ toes. But he was willing to share a few thoughts.

He called Prozac “the big bang” of pharmaceutical naming.

“That’s what started the blockbuster brand naming process,” Piergrossi said. “It doesn’t mean anything. It’s a blank canvas. Obviously, the ‘pro’ is a positive prefix: professional, strength. And the ‘zac’ suffix is just easy to pronounce, punchy.”

His team worked on the name for Jeuveau, which is a dermal filler (read: anti-wrinkle). “It has that very youthful feel because it’s in the French language,” Piergrossi said. In French, jeune means young and nouveau means new, so it connotes something akin to “young again.”

Another recent product they worked on: Opill, the new over-the-counter birth control pill. Piergrossi said he likes several aspects of this name. “Its simplicity, its reference to ‘the pill,’ its reference to the oral contraceptive — the oral pill — and it’s a very easy to remember name,” he said.

So, next time you look at a drug name, look for the implied meaning beneath the syllables. You can assume it’s the result of months of work — not a spontaneous yelp at the end of a meeting.

Sign up for the CommonHealth: Boston's Weekly Health Newsletter