Advertisement

Without a home, a cancer patient on the waitlist for public housing puts off surgery

With every passing week, Deb Libby's search for a home becomes more dire.

The 57-year-old woman was evicted from her Worcester apartment last month and she said she can't find another place she can afford. She borrowed money to stay a few days in an Airbnb, then a week in a cheap motel room. Now she’s staying at a small homeless shelter in Worcester.

But Libby said she needs to find permanent housing soon. Doctors discovered that her pancreatic cancer has spread to her liver. She needs surgery to remove the cancerous cells, but knows she can't handle the operation until she has a long-term place to recover.

"I'm terrified," she said. "I can't even cry. I can't sleep. I get sick to my stomach. I can't eat."

Deb Libby is one of the more than 180,000 people on the waitlist for state-funded public housing in Massachusetts. WBUR first met Libby over the summer while our journalists were investigating the public housing system.

WBUR and ProPublica discovered nearly 2,300 units of state-funded public housing were vacant as of the end of July — many for years. Reasons for the vacancies include a flawed online system that the state created for selecting potential tenants, as well as lack of funding for maintenance, renovations and staff. WBUR found the state has spent millions of dollars a year to maintain the unused units.

Following the investigation in late September, Massachusetts housing officials announced a 90-day push to fill as many vacant units as possible by the end of year.

Kevin Connor, a spokesman for the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities, said the agency believes there will be a “significant reduction” in empty units.

Advertisement

So far, local housing agencies have eliminated 143 vacancies since the end of July, according to Connor. That accounts for 6% of all the unused apartments.

Over the years, Massachusetts has built the biggest state public housing system in the country to help provide subsidized apartments to low-income individuals and families. Residents of these units pay deeply discounted rents — less than one-third of their income, or only $5 per month if they have no income. But demand has far outstripped supply.

“The bottom line is that we have a serious problem in the commonwealth with availability of affordable housing,” said Alex Corrales, chief executive of the Worcester Housing Authority.

That reality has left people like Libby in limbo. She first applied for public housing and vouchers in Worcester more than a year ago after she received an eviction notice. The Worcester Housing Authority estimated people must wait up to five years for public housing in the city. She's now on the waitlist in more than 30 communities.

Libby never thought she’d be homeless. She said she always worked and even owned homes in the past.

Then she got cancer and eventually became too ill to work her old job at a hardware store, where she had to lift heavy bags and walk miles a day.

With the help of free legal counsel, Libby was able to stave off eviction for a year.

As part of an agreement to settle the case, the landlord acknowledged Libby was not at fault, promised to provide a good recommendation and cited unspecified “economic reasons” for the eviction.

Libby finally had to move out of her one-bedroom apartment in Worcester in late October.

Everything she owned was divided into one of three places: Her 2001 pickup truck, a storage unit in a nearby town … or the curb.

"If you see anything you want, you can have it," she told a WBUR reporter as she tossed items away and loaded crates onto the back of her truck.

There were some things Libby couldn't throw away. She showed off a gold necklace around her neck, with a light blue sapphire, that her children gave her decades ago when they were little. She said she wears it all the time.

She didn't have enough cash for a hotel room. So she borrowed money in “kind of a loan shark thing” to stay in an Airbnb in Worcester for the first few nights. Then she moved into the cheapest motel room she could find in the county, paying $99 per night for a room near Old Sturbridge Village with blood orange walls and thick gold drapes hanging over the window looking onto the parking lot.

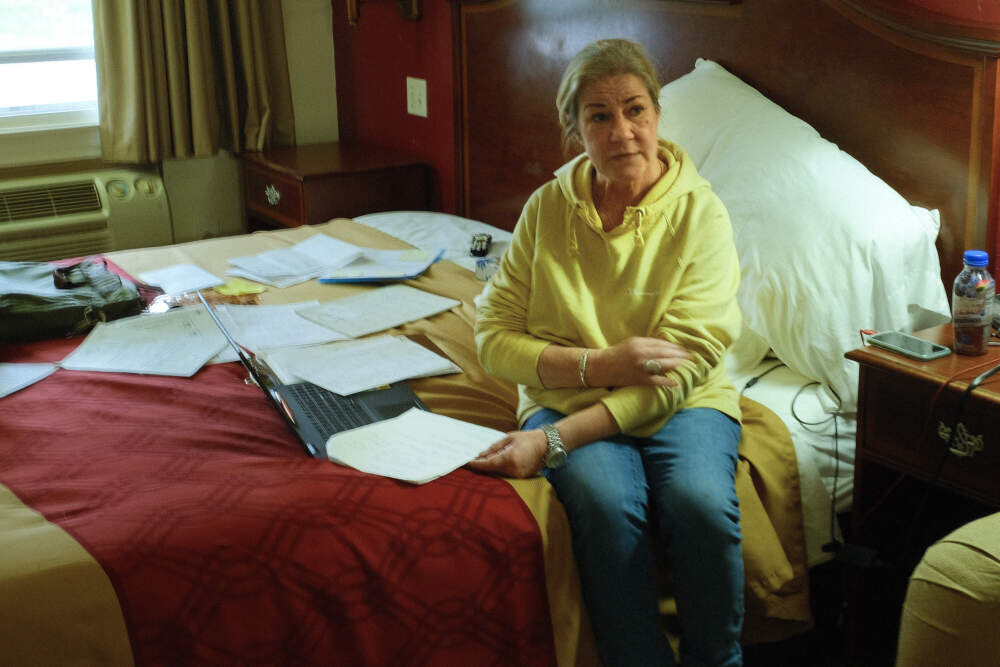

When a WBUR reporter visited her at the motel room, she had turned her bed into a mini-office with a laptop, clipboard and piles of papers. Then she called one homeless shelter after another, scribbling notes to track her progress.

Many told her they were already full. But she mostly got stuck on hold or left a message.

“This is all day,” she said, after leaving yet another voicemail.

She sounded exhausted just reading the list of all the shelters she called.

“Leominster, Worcester, Dorchester, Northampton, Beverly, Boston, Cambridge, Taunton, Westfield,” she said, turning the page. “There's a place in Ashland. There was a nice person that I talked to there, but they didn't have anything for at least eight weeks.”

Unfortunately, for Libby, there is no complete list of shelters with openings in the state. And she was running out of time and money.

She knew she couldn’t stay in the motel much longer and worried she would eventually have to sleep in her truck, even though it was already stuffed with belongings. She figured she could find a cheap gym that had a shower and bathroom.

She wishes the government would do more.

“It's very frustrating,” she said. “I've been a citizen. I've paid taxes. I've done what I'm supposed to do and I can't get the slightest bit of help.”

After a week in the motel, she finally got a small break.

She learned a small Worcester shelter had a free room. Libby’s been there for a week so far, but doesn’t know how long she can stay.

Her health is deteriorating and the cancer is spreading. She said she needs the surgery — and a permanent place to live. “It needs to happen,” she said. “I can't keep putting this off.”

She has trouble eating, so she mostly consumes juice drinks and soup.

“I've lost a lot of weight,” she said. “Even my doctor was like, ‘Hey, you gotta start to eat.’ I'm like, yeah, I would if I could. It just doesn't stay down.”

Libby still hopes to eventually land a place in public housing. She just has to wait.

“What am I going to do? Give up and live under a bridge?” she asked. “It's not an option.”

This segment aired on November 21, 2023.