Advertisement

'The Highest Standard' explores chasm of race, identity and an elite education

Since its founding in 2004, Beacon Academy has been dedicated to helping prepare Boston-area students from underprivileged backgrounds gain admission to elite New England private and independent high schools in hopes of expanding their future opportunities.

Its core program takes place between the eighth and ninth grades as an additional year of schooling, including summers. Admitted students are immersed in rigorous academic instruction and out-of-classroom activities over a 14-month period, while guided through the private school application process for the start of high school.

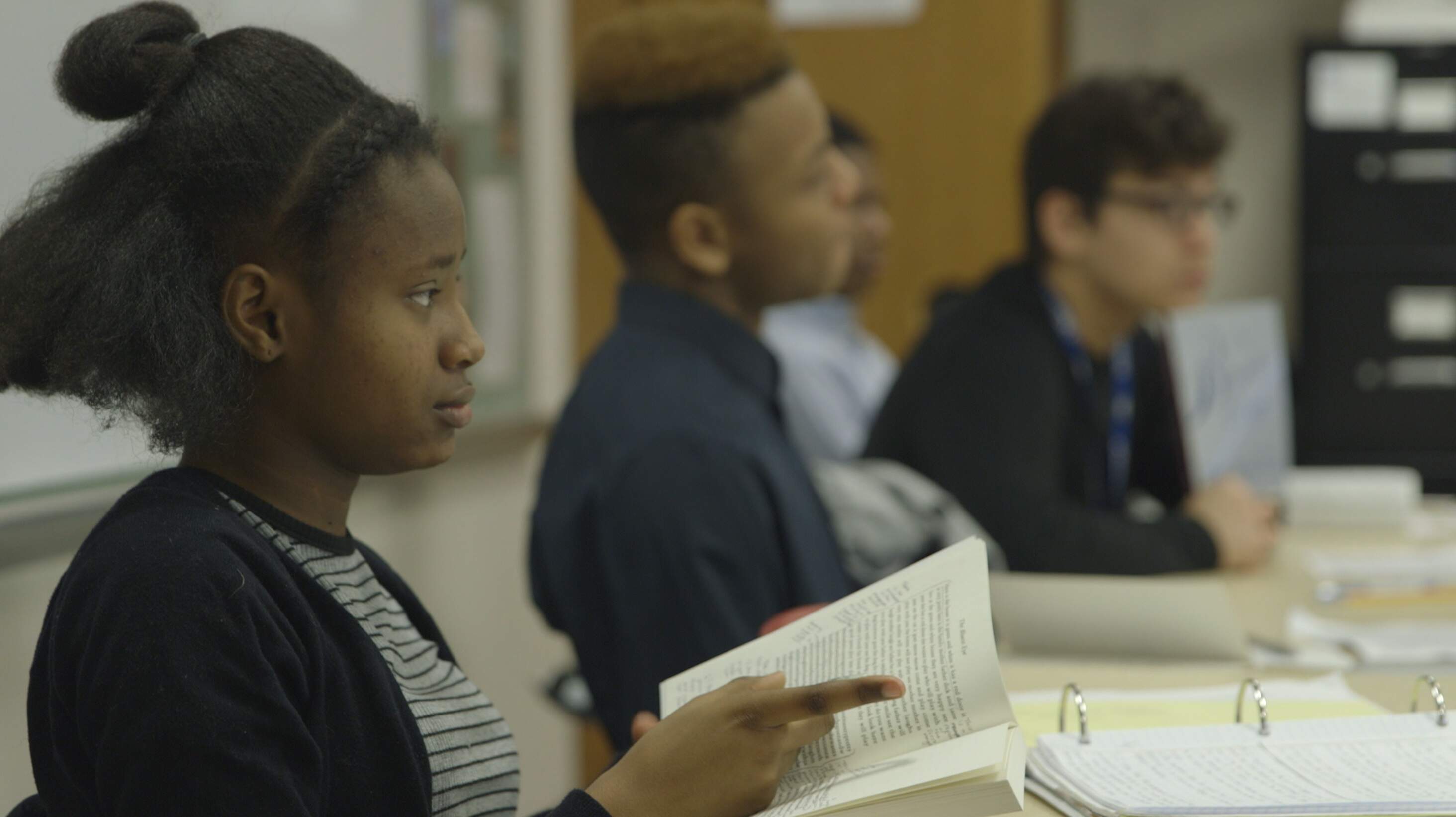

The stakes of this formative year are captured intimately in a new feature documentary, “The Highest Standard,” which premiered in October 2023 to a packed theater at the GlobeDocs Film Festival. Filmmaker Isara Krieger brings us inside Beacon Academy in late 2016, chronicling students’ experiences and reflections up until they await schools’ decisions by the following spring.

Then housed in a wing of Temple Israel in Boston (the academy has since moved to its own space in Roslindale), Beacon serves predominantly students of color from public middle schools around Boston, who show high academic promise and potential but whose reading and math performance is closer to fourth-grade level when they first enter the program. Tuition is covered for families based on financial need.

The school’s mission is to prepare a class of up to 25 students not just academically but via other intellectual, creative and cultural pursuits to broaden their exposure. In the film, Beacon’s founding faculty member and then-head of school Mervan Osborne notes that the goal is to level the playing field given educational disparities between city students and suburban kids in Massachusetts.

“We’re looking to find kids who can be competitive with those suburban kids,” he says. “You’ve got to make them believe that they’re entitled to the same level of education that people of privilege get access to.”

That central tension – whether an elite, private school education is a ticket to success for these kids — is the push and pull at the heart of “The Highest Standard.” And it’s the question of who gains access to these spaces and the challenge of navigating them that breathes an added layer of complexity in the film’s final chapter.

Krieger, a Boston-area native who attended the private Buckingham Browne & Nichols School in Cambridge before transferring to Boston Latin School in seventh grade, says she was compelled to make this documentary due to the stark educational gaps in the region.

“These are young students who are doing the reverse journey of what I did, with very different life circumstances, too,” Krieger, who is white, said in an interview.

Leading us through that journey are three central characters: students Meleah Neely, Makai Murray and Exavion Clerveau who, in close-up interviews early on in the film, share their goals and realities of past school environments. Says Meleah, who dreams of attending Harvard and writing a book, of why it was hard to fit in at her Boston public school: “The cool thing was not doing your work and getting Fs.”

Krieger says she focused most closely on these three, because though “still so kid-like, they also had the glimmer of adulthood in them,” she said. “They weren't trying to be anything but themselves and I sensed a propensity for self-discovery in them.”

Beacon Academy’s student body reflects the racial makeup of Boston Public Schools as a whole: roughly one-third of students in the district identify as Black and more than 43% as Hispanic, while white students make up just 15%, based on most recent districtwide data. Among independent schools in Massachusetts, more than half the kids are white and just 5% of kids identify as either Black or Hispanic, and another 8% as mixed-race, according to the National Association of Independent Schools.

Options exist for high-performing district students, such as the three competitive exam schools or METCO — the program that places Boston kids in suburban public schools in predominantly white, wealthy areas. But fewer gateways exist for kids in that middle range, says Osborne: those who may be “C students” at their neighborhood schools but who demonstrate high potential, grit or a quality that stands out to instructors.

“A teacher would write something, and those recommendations from teachers matter so much,” he said of Beacon’s admissions criteria. “Because a teacher could tell you — this is a great kid, this is a wonderful kid.”

The program focuses on intense academic preparation but also on cultivating a sense of community and shared identity among participants. “The Highest Standard” captures these moments, whether it's a classroom discussion of Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” or light banter with other students and teachers. The film also takes us outside school walls, following students as they study paintings during a trip to the Museum of Fine Arts or analyze and discuss the racial underpinnings of a 1939 black-and-white photograph from which the film derives its title.

Scenes that bring us deeper into students’ home lives and their relationships with adult figures remind us of the importance of their support networks, such as a family dinner at Makai’s mentor’s home, or a car-ride conversation between Makai and his mother following their visit to Tabor Academy, a prep school near the Massachusetts coastline. The film crescendos up to the unbridled (and in some cases tempered) joy on March 10, 2017 when Beacon students learn whether they’ve been accepted into the schools they’ve applied to, and, crucially, how large a financial aid package they’ve received.

The film doesn’t end with this climactic moment. It jumps to spring 2021, when Meleah, Makai and Exavion — now young adults — are set to graduate from their respective private schools across bucolic New England and enter college. Signs of the times abound: face masks from the pandemic and references to the racial reckoning sparked by events in 2020. They’ve blossomed as student and campus leaders but also reflect on the isolation and shock they felt being among the few Black kids on campus. “I don’t think they identify their white privilege sometimes,” Exavion says of his peers. “I feel they step around glass around people of color when they should just want to have these uncomfortable conversations or like educate themselves.”

Krieger said that realization presented tough questions. She said in some “ways that the (students) had to, shift, kind of shut down some of their true selves to fit into these elite environments.” “Is it even fair to be telling these students that in order to have a good life or to succeed, you have to go down that path?” she says.

Osborne, now the associate head of school for student life at St. George’s School in Middletown, Rhode Island, which is also his alma mater, said he understands that struggle as one of the few Black students at the school in the 1980s. But he believes in Beacon’s mission to open doors. “The tradeoff, the payoff for having the proximity to some of these opportunities that only certain people who win the genetic lottery get to have access to, was worth, is worth … navigating the journey,” he said.

Krieger has kept in touch with the students she’s filmed. Seeing their younger selves in the documentary, she says, has helped them keep processing their identities. At October’s screening at the Coolidge Theater, she was joined on stage by the film’s producers and Makai, now a junior majoring in art history at Tufts University, during an audience Q&A.

As for Beacon Academy, Krieger adds it's "one solution for a really complex problem" when it comes to the education and opportunity gap in the region, but one she was "curious in investigating" through the making of the film.

“The Highest Standard” plans to host additional screenings around Boston and the New England region this year.