Advertisement

A new study highlights the long-term benefits of METCO participation

A new study sheds light on the long-term effects of the popular METCO program, which sends thousands of Boston students to learn in suburban school districts each year.

Twenty years of longitudinal data suggest that participating in METCO, which stands for the "Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity", has a range of benefits for students, from higher MCAS scores to better college and career outcomes, when compared to other educational trajectories.

Lead researcher Elizabeth Setren, a Tufts University economist, previewed her findings during a presentation at The Boston Foundation Tuesday morning.

This latest research finds that METCO’s effects aren’t always dramatic or even uniform: boys seem to benefit more than girls, and first-generation college students appear to get more out of participating than those whose parents have college degrees.

But in general, Setren found that — nearly 60 years since its launch — METCO has measurable benefits for its participants, with no negative effects on students who live in the 33 hosting suburban school districts.

The METCO program was founded by a coalition of parents, activists and academics in 1966 to combat school segregation. It counts former city officials — including Kim Janey and Tito Jackson — and NPR journalist Audie Cornish among its graduates.

At Tuesday’s event, program graduates spoke to its lasting influence on their lives.

State Rep. Chris Worrell, who traveled from Dorchester to schools in Lincoln-Sudbury, said the experience “opened his eyes” and made him comfortable in majority-white spaces — including Beacon Hill.

All children who legally reside in Boston are eligible to apply, but since 2019, students are admitted to the program based on a randomized lottery. With just a few hundred openings available each year, many more are turned away.

Between 2005 and 2017, Setren found that nearly three-quarters of both applicants and participants were Black, and that nearly half of Boston’s Black students apply to the program at some point. Meanwhile, the city’s Latino and Asian students, immigrants and those with disabilities are underrepresented in the program.

This school year, METCO sent roughly 3,200 city students to 33 school districts across greater Boston, from Newton and Brookline to Reading and Foxborough.

By linking data from METCO, the Mass. Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and other state agencies, Setren reviewed the long-term experiences of approximately 20,000 Boston students who applied to METCO between 2005 and 2017.

Setren and her team compared the outcomes of program participants to others who applied but weren’t admitted to METCO.

The researchers found that nearly three-quarters of students who couldn’t secure a spot in METCO had left the Boston Public Schools by ninth grade, with many having moved out of the city or enrolled in charter or private schools.

Meanwhile, nearly half of admitted students stuck with the program from kindergarten to 12th grade.

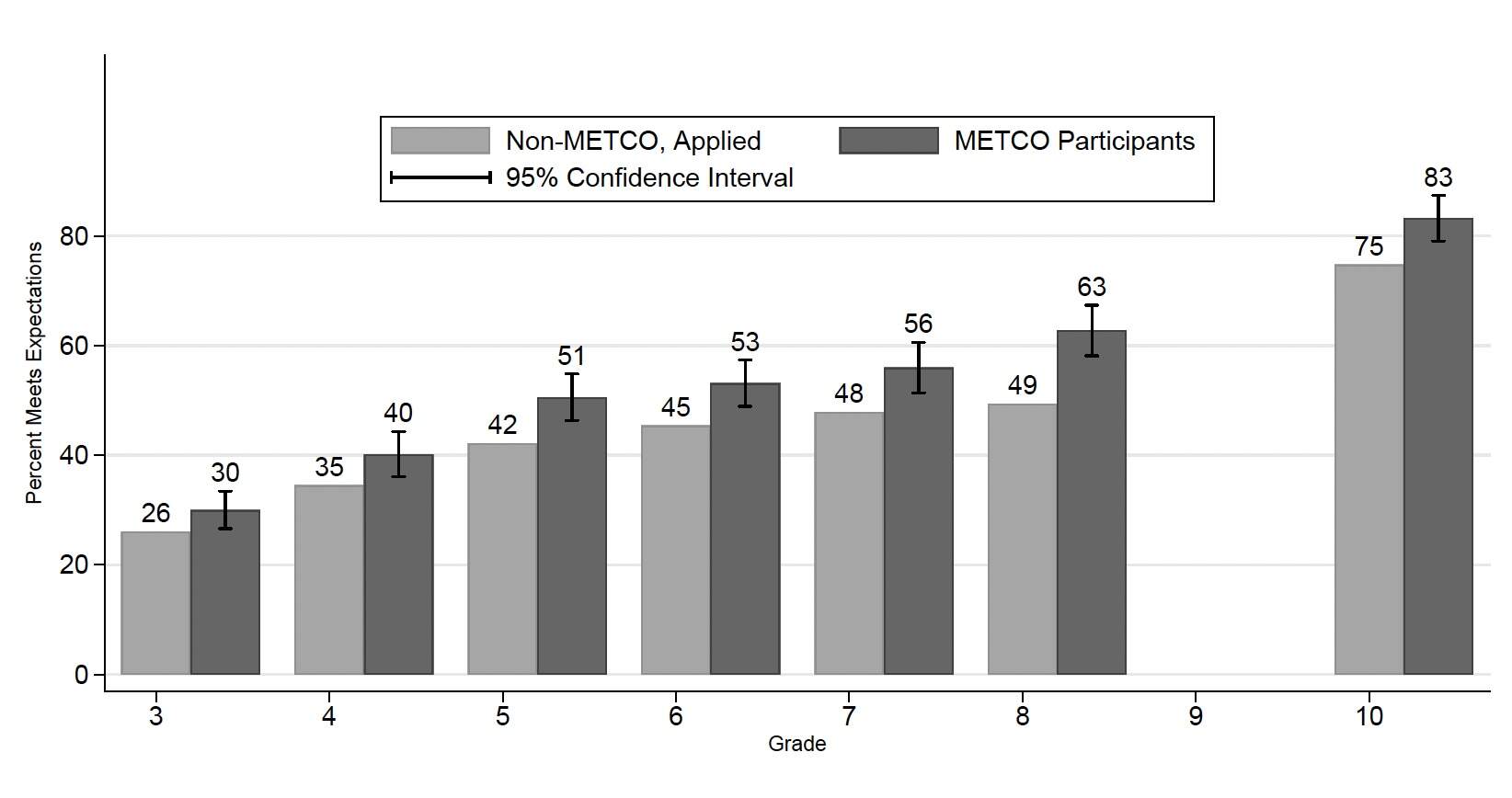

Using MCAS scores, the study found that academic effects of METCO participation started early and grew over time.

But the study also found little to no effect in other areas: for example, participants were not more likely to take Advanced Placement classes or to get an SAT score of at least 1200.

“Even though METCO participants are enrolling in schools with access to more rigorous coursework, they are more likely to be in relatively lower-performing math and English courses,” Setren said in an interview Tuesday.

METCO staff and education officials are looking into the underlying causes of that phenomenon, she added.

On balance, though, the data suggest remarkable long-term advantages to taking part in the program, including a 33% reduction in the risk of dropout, a 17% increase in rates of four-year college attendance, and a more modest increase — of around six percentage points — in rates of graduation from a four-year college or university.

Because the quantitative study works with “large, administrative data,” Setren said, it’s easy to measure the program’s effects — but “much tougher to get at the why.”

At Tuesday’s forum, METCO president Milly Arbaje-Thomas said the answer may lie, in part, on differing expectations based on students’ school cultures. “For METCO students, the question is, ‘what college I’m going to go to.’ For other [Boston] students, it’s ‘if I’m going to college,’” Arbaje-Thomas said.

As a program parent, Arbaje-Thomas said she has witnessed firsthand the “trade-offs” involved with METCO participation, including the sense of identity crisis for students of color attending predominantly white schools.

But Arbaje-Thomas added that “at the end of the day, what I have seen is the closing of achievement gaps for our students.”

Whatever the cause, closing those gaps appears to make a lifelong difference. Setren’s study shows that by age 35, METCO students had markedly higher rates of employment, along with average annual salaries that are higher by over $24,000 a year than peers who applied but weren’t admitted.

Setren plans to expand her research to examine the program’s less tangible effects, including rates of social integration in schools, teen pregnancy and voter registration.

As the product of diverse Baltimore County schools, Setren said she has been “fascinated” by METCO since she was an undergraduate at Brandeis University. This latest research came together over the past six years.

Setren hopes her research will shed light on a long-running program to integrate schools.

“As an academic, my interest is mostly to inform policymakers and practitioners on the ground,” she said.

But, amid a slide back toward school segregation, “we can learn a lot from METCO” and its successes, she added.