Advertisement

'Lynching Tree' at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum highlights uncomfortable truths

In the spiritual world, oaks are symbols of wisdom and strength. It was the sacred tree of Zeus. The Pechanga people of the Western United States have a 1,000 great oak on their reservation, a tree they believe represents longevity and determination.

There is a dark irony in the fact that oaks, and other big trees like them, were the site of an estimated 4,400 “racial terror lynchings” that happened throughout the country between Reconstruction and World War II. Racial terror lynchings targeted victims based on race and consequently, reinforced and maintained racial caste systems in America.

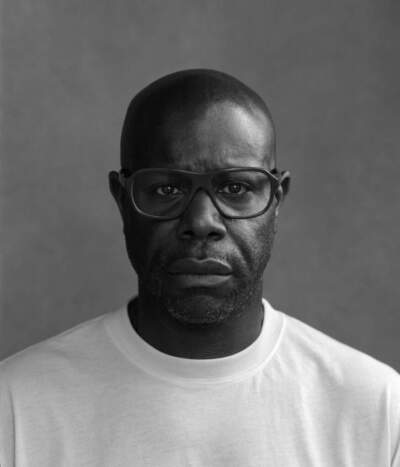

Filmmaker and artist Steve McQueen’s “Lynching Tree,” on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum from Jan. 20 to Feb. 4, takes a look at one such tree. This is only the second time “Lynching Tree” has been on public view in an American museum.

When Lee Pelton, president and CEO of The Boston Foundation, first saw “Lynching Tree” in 2022 at the Yale Center for British Art, he felt an overwhelming rush of emotion. “I could imagine, I could see, I could feel, I could taste the unimaginable events that had actually occurred there,” Pelton says. “I sobbed convulsively for several minutes … it had a profound emotional impact on me.”

It’s a singular photograph of a large oak. McQueen took the photo while scouting locations for his 2013 film, “12 Years A Slave.” The oak, which sits somewhere on a former plantation near New Orleans, is nestled among unruly bushes along an overgrown dirt path. It seems like a serene enough setting but the tranquility of the image belies the dark history tied to the oak and other trees like it. The image is illuminated from behind, soft light bleeding around its edges.

Lee’s visceral reaction prompted him to see if there was a possibility of bringing “Lynching Tree” to Boston. He contacted Peggy Fogelman, director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “The effect it had on him made me even more interested and eager to bring this work to Boston,” says Fogelman. Lee and Fogelman co-curated the exhibit.

Lynching may have happened more frequently in the South, but the terror of the act still concerned Black people and their allies in the North. Local writers like Pauline Hopkins of “The Colored American” decried lynching while “The Liberator,” the Boston abolitionist paper run by William Lloyd Garrison, published an issue with a drawing of a lynching tree on the front page. “I think that we often assume that these violent acts were relegated to the South,” Fogelman says. While there are no documented lynchings in Massachusetts, there is one on record in New York and one in New Jersey.

“Lynching was an act of terrorism,” explains Pelton. “But I think that some people don't fully realize how horrific it was. It was a celebratory event that people brought their kids to. Bodies were burned, pieces of flesh were cut off and kept as souvenirs, postcards were made and kept and remembered.”

Grisly as it may be, it’s an important and pertinent truth that, for many decades, Black death became an American pastime. The tree is a reminder that the quintessential American landscape contains horror too.

The pain of lynching does not go away, partially because the practice has not been exterminated. It has merely been transformed and transmuted, Lee says. “Lynching can take many forms … When [Derek] Chauvin had his knee on a Black man’s neck, who was crying out for his momma, that was a lynching.”

The photo coming to Boston is important. It highlights the fact that the North has its own sites of terror that it has yet to contend with. From King Philip's War to the Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, Boston has ghosts that have not been adequately addressed. “We all have to grapple with our very problematic histories,” says Fogelman.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum as a site helps provide a different context for the photograph. The live and colorful courtyard offers an interesting contrast to "Lynching Tree." "We have this amazing courtyard that blooms all year round," says Fogelman. "That kind of juxtaposition really speaks to the hidden scars that nature can hold of our violent history." Nature can hold horror, but it can be a balm, too.

Though “Lynching Tree” is only on display for two weeks, the timing of the show is serendipitous. It’s the 10th anniversary of “12 Years A Slave” winning an Academy Award and the 50th anniversary of the Boston busing crisis. “It’s also a moment when African American history is being suppressed in its teaching in schools, and its dissemination in books through book bans and other kinds of legislation,” Fogelman points out. “It was very timely and important and urgent that we show it now.”

“Lynching Tree” raises questions about the past and present of lynching in America. It is a looking glass through which we can catch a glimpse of the dark history that impacts our present. As McQueen puts it, the photo forces us to contend with the fact that there’s a responsibility that comes with awareness.

“I quote James Baldwin, probably on a daily basis,” says Lee. “He said that 'Not everything that is faced can change, but nothing can be changed until it's faced.' … That's what this exhibit is about, facing uncomfortable truths. Because that's where change happens, in those moments.”

"Steve McQueen: Lynching Tree" is on view at the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum from Jan. 20 through Feb. 4. Visitors are encouraged to reserve tickets in advance.