Advertisement

'A way to escaping': Cape Cod prisoners hit the books in jail library

Resume

The Barnstable County jail has long had a library, as is typical at correctional facilities in Massachusetts. But Barnstable's book collection fell into neglect during the pandemic, when the jail lost its librarian.

Along came Brian Stokes.

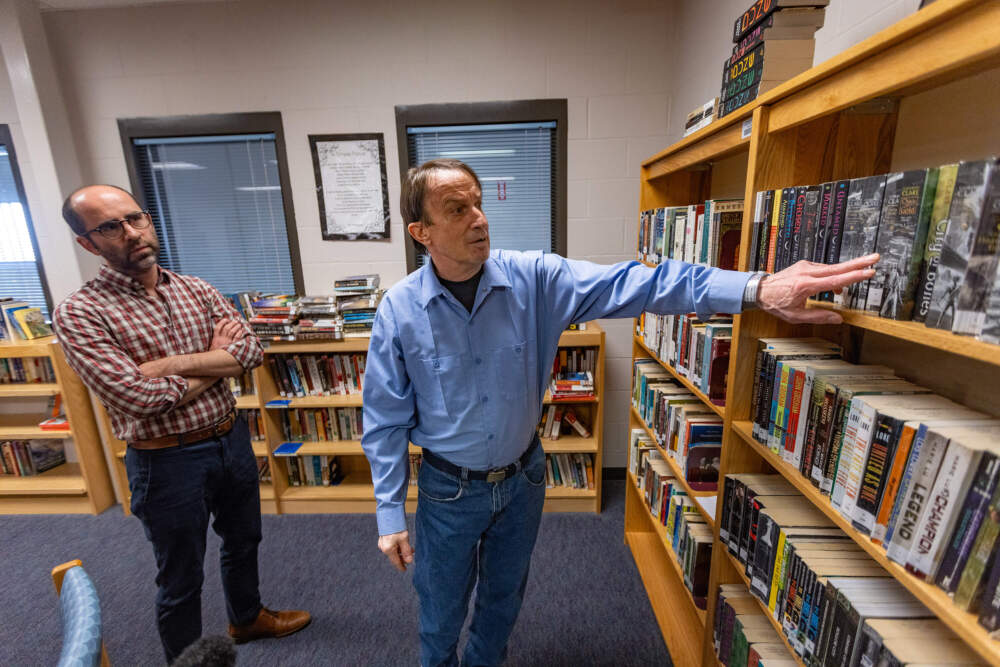

Last summer, as the new acting director of the Falmouth Public Library, he reached out to officials at the jail, a short drive away on Cape Cod. He volunteered to help get Barnstable's library back in order.

"When you have just this giant blob of fiction, it can be overwhelming," Stokes said. "People don't really know where to start, so genre is important, subsections are important."

And then there's basic organization: "just getting things alphabetized so that when you do come in and you only have 20 minutes, you're not looking for a needle in a haystack."

Stokes is not a newcomer to this setting. Earlier in his career, he worked in a library at Rikers Island, New York City's largest jail. While Barnstable is relatively tamer and much smaller than Rikers, the facilities share some characteristics: Many of the prisoners are awaiting trial and have not yet been convicted of crimes; those serving sentences in Massachusetts jails are locked up for a maximum of two-and-a-half years; and more serious convictions result in state or federal prison time.

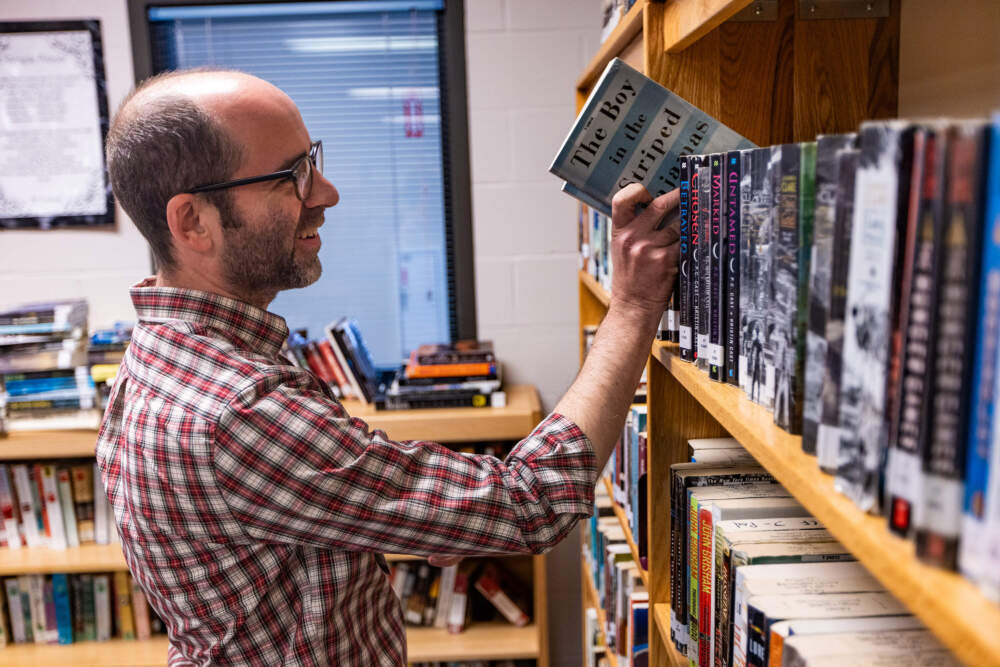

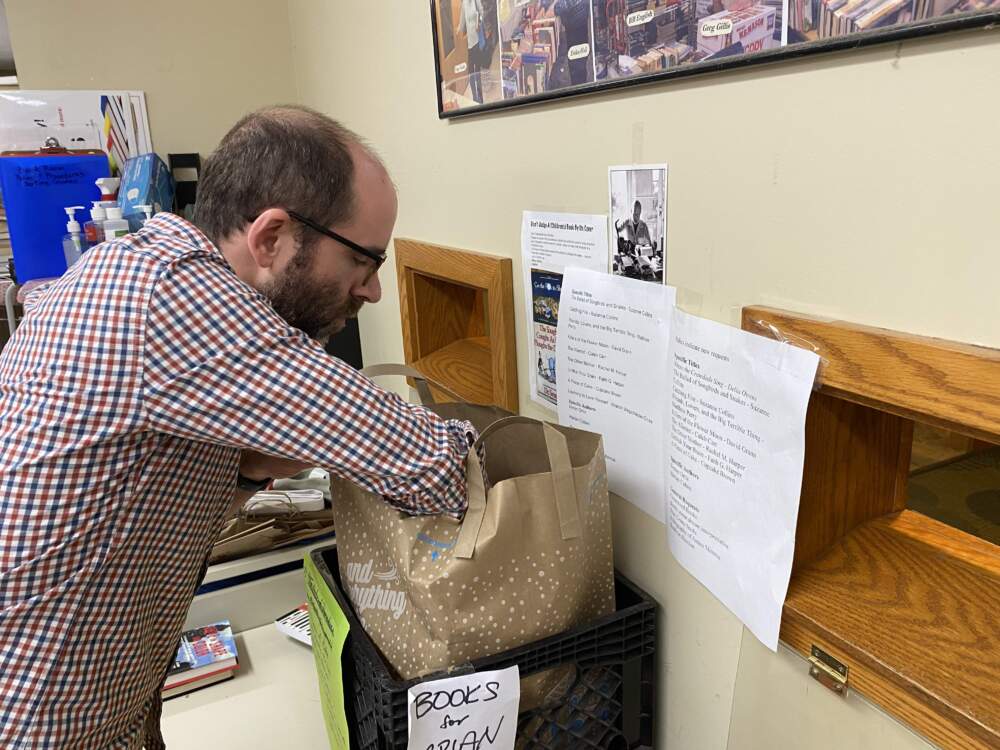

But even a few months behind bars leaves inmates with a lot of time on their hands. Every week, Stokes walks into the Barnstable jail with a brown paper bag. Inside are books requested by prisoners that he’s been able to find thanks to donations from readers in Falmouth. Fantasy series are particularly popular behind bars, he said, as well as "airport fiction" like John Grisham and James Patterson. Colleen Hoover is heavily requested among female inmates.

The library is in a small carpeted room inside the jail. Its walls are lined with oak bookshelves divided into genres: young adult, fantasy, non-fiction. Before COVID, inmates could only pick books from a cart that staff would roll around the jail. Now they get to visit the library for 20 minutes a week.

Sitting in the library one recent afternoon next to several staff members was John Sheehan, 59, who's serving a sentence for stealing construction tools from a hotel. (He denies stealing the tools.) He said he's reading everything from ancient history to theology — though he sticks mainly to fiction.

"It's kind of a way to escaping," he said. "I probably shouldn't use that word in here, but yeah — to take my mind away."

Inmates at the Barnstable County jail have a saying, according to Sheehan: Do the time, don’t let the time do you.

"What that means is, 'I know we're in jail, but do positive things while we're in here, as opposed to just sulking about why we're in here,'" he said.

It's not Sheehan's first time in jail. His first stop on this occasion was to visit the nurse's station for a pair of reading glasses.

"That's like the first thing I do every time I come in is make sure I can read," he said. "It's a very important part of what I do while I'm in here."

Barnstable County's new sheriff, Democrat Donna Buckley, sees library services as part of the jail's rehabilitation and education efforts to reduce recidivism. She succeeded Republican Sheriff James Cummings, who held office for 24 years. And Buckley has been making changes.

"There are going to be many more opportunities for us to use the library in a way that is transformative, both while people are here, and most importantly: how will it help when people are released?" she said.

"It's kind of a way to escaping. I probably shouldn't use that word in here, but yeah — to take my mind away."

John Sheehan

Back on his home turf at the Falmouth library, Stokes sorted through titles set aside for the jail.

The books must be soft-covered; hard covers can be used to fashion weapons or hide contraband. And Stokes is trying to establish a longer-term bridge between the jail library and the public library in Falmouth.

"When you get out of an incarceration setting, you haven't been paying your bills maybe, and you don't have somewhere to live," he said. The library is a reliable place to access information and free resources.

While Stokes is a volunteer, advocates say every jail and prison should have its own librarian. Without one, they say, libraries can fall into neglect.

"You need that professional curation, you need that professional input," said Ally Dowds, a librarian at the state Board of Library Commissioners who serves as a liaison with prison library programs. "You're not just putting books on a shelf."

Dowds said the role of libraries is to curate a collection for the needs of one's community, whether that's a public library or an academic library.

"Why would you not do that in a prison library?" she said.

In some countries, prisoners’ access to books is treated as a human right. A study from the United Nations reports that in Norway and Finland, wardens have to give library access to all incarcerated people. In 2012, Brazil began allowing prisoners to reduce their sentences by reading books.

Here in Massachusetts, libraries vary widely at every county jail and prison, according to Michael Wood of the Quincy-based nonprofit Prison Book Program, which serves all 50 states and most jails and prisons in Massachusetts. Larger facilities often have more resources. At the Suffolk County House of Correction in Boston, inmates have access to 20,000 books and 50 periodicals, as well as two staff librarians.

Wood said it's common for new sheriffs or prison wardens to liberalize policies on receiving books from his organization — while others clamp down on receiving outside books in the mail.

“It comes down to whoever’s in charge," he said.

Wood said seven of the state's 13 sheriffs that run jails do not allow books from his program, while all the state prisons do.

“It’s the locals that are a problem,” he said. “We’re working on it. They say 'no,' we call again in six months.”

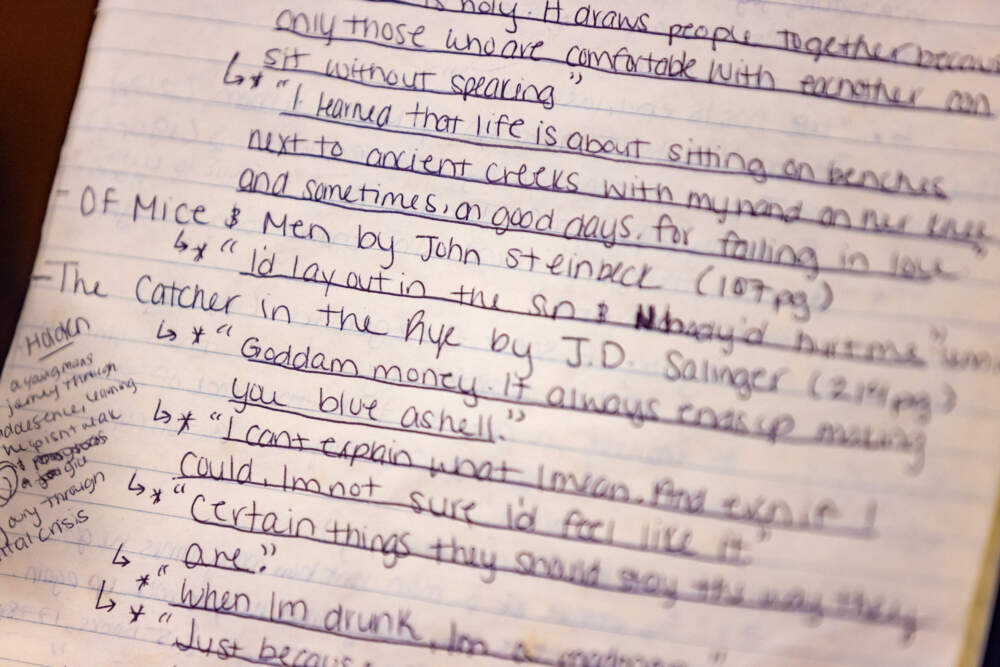

At the Barnstable County jail, Tianna Hutchinson said books are playing a big role during her year-long sentence.

"It’s a life-changing experience," she said. "It's something I wouldn't have expected to get out of [being locked up], but it's just truly amazing to be able to read this much."

Just past her 21st birthday, Hutchinson was involved in a head-on crash in Middleborough, and she was convicted of vehicular homicide. She said time behind bars — much of which she spends with characters like Scout Finch and Jay Gatsby — leads her to reflect on how she wants to live when she's free.

"This can happen to anybody you know in life," she said. "I just hope that someday I can use what I know, and what I've been through, to help somebody else do better."

By itself, a library won’t change Hutchinson’s life. But she said books are making her a better person than the one who first walked into this jail in handcuffs.

This segment aired on January 23, 2024.