Advertisement

Boston journalist Carmen Fields tells the story of her father's territory big band

When Carmen Fields was a little girl, she wished her father would be like all the other dads who “came home with a briefcase at 5 o'clock every day.” But over time, she came to realize that Ernie Fields’ long absences from home were because he was leading a jazz orchestra that would become one of the longest-running outfits of the big band era.

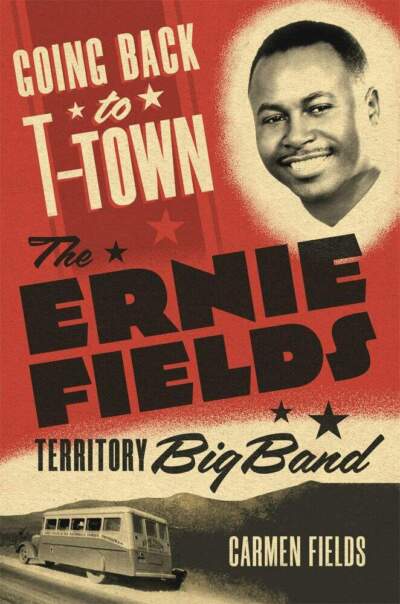

Now Fields, a veteran Boston journalist, has turned her trombonist father’s story into the book “Going Back to T-Town: The Ernie Fields Territory Big Band.” This fascinating work chronicles her father’s life on the road during Jim Crow, a recording career that spawned hit records in both the swing and rock eras, and how he maintained a band that gave many future jazz greats their first breaks.

Carmen started working on the book more than a decade before Ernie Fields died in 1997. She remembers a time when Ernie was visiting Boston and a local music writer came over to interview the bandleader. “I realized that he had more photos of my daddy than I did,” she laughs. “The light bulb went off and I realized that we have something special, that other people recognize it, and that I needed to do what I could to capture and preserve that.”

Fields recorded hours of interviews with her father and many of the musicians who passed through his band. But some of the book’s most riveting moments come from letters that Ernie Fields wrote to his wife telling her about life on the road, the financial challenges of keeping the band going, and his joy of discovering that his son had been born while he was on tour.

“One day, my mother quite unexpectedly handed me a package wrapped in plastic, which is probably the worst way to keep something secure from the elements, and said ‘take a look at these.’ And I sat down and started going through them, and I was just amazed,” says Fields.

Her father led what was called a territory band. Fields explains that in the big band era, jazz groups often performed principally in a specific region. “For example, my father was based in Tulsa,” she says, “and his territory typically went from Dallas to Kansas City.”

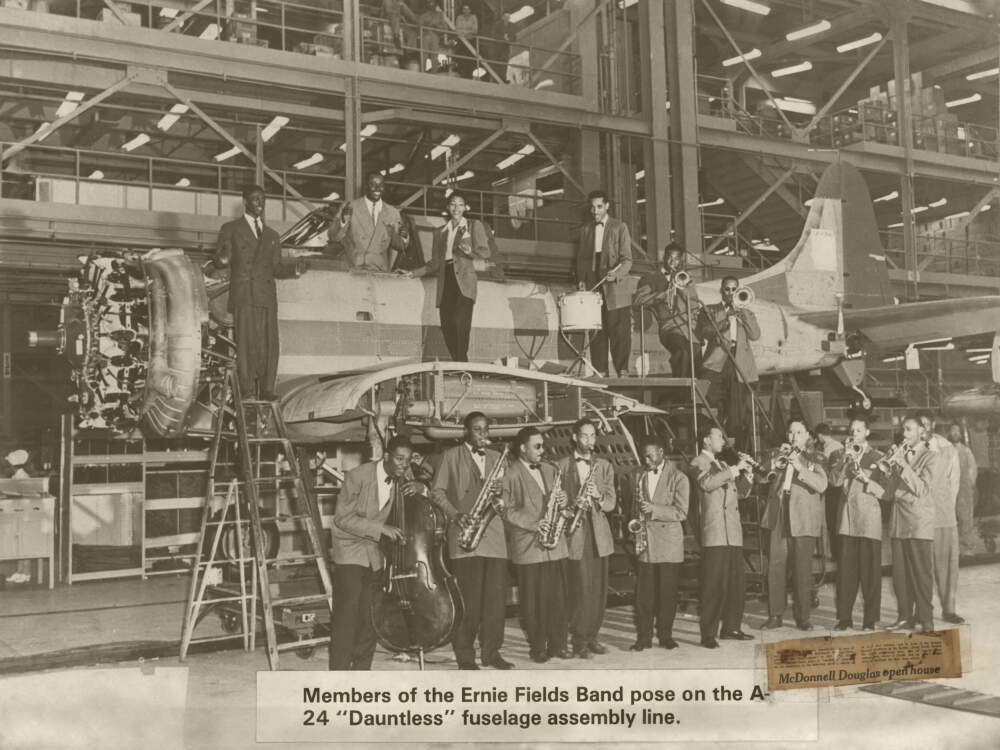

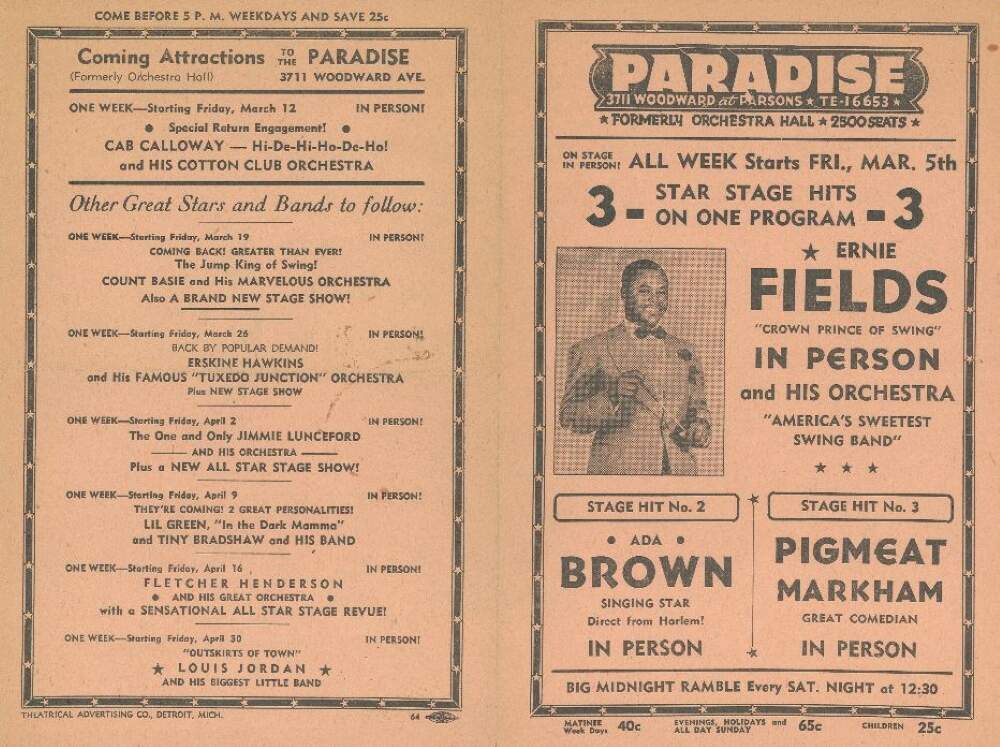

Unlike many other territory bands, Fields’ unit also traveled all around the U.S. In 1939, famed producer John Hammond convinced the group to relocate to the East Coast, although the stay was short-lived. The group had a Berkshires booking agent and would often play dances from New Haven, Connecticut to Old Orchard Beach, Maine. During that time, Fields recorded the hit “T-Town Blues.”

In 1959, long after most other big bands had folded, Fields, at 54, had an even bigger hit with a rock spin on “In the Mood.” “It was a surprise because he was just about ready to hang it up, but that really reenergized him,” Carmen recalls Carmen.

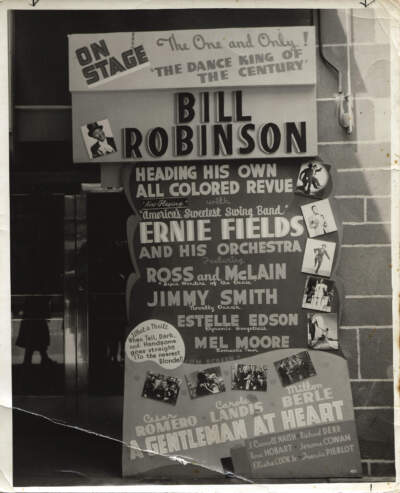

While on the road, the Fields band backed Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and a then-unknown Marvin Gaye. Just a few of the major jazz and blues figures who passed through the band included Yusef Lateef, Don Byas and Roy Milton. One night in St. Louis, the band needed a sub so they hired a local trumpeter named Miles Davis. Fields thought Davis played too quietly and didn’t take him on the road, something his bandmates would rib him about for decades.

Touring during Jim Crow provided obstacles that even went beyond the challenges of finding food and lodging. When the band’s bus broke down in an especially unwelcoming community, the musicians had to push it over the town line while they waited for the repairs to be finished. While Benny Goodman is credited with integrating jazz by hiring Black musicians, Fields claimed to be the first Black bandleader to hire a white player. He also had a long friendship with Bob Wills, the country music bandleader who popularized Western swing. “His name was revered in our house,” says Carmen. She recounts that venues reluctant to hire a Black band would be told by Wills “that if you don’t hire Ernie Fields I’m not going to perform there anymore.”

The book reveals how at a time when there were many big bands seeking work Ernie Fields stood out by insisting that his band appear sharp on stage, and by commissioning unique arrangements. “He loved to have something a little different than the typical way that songs were being arranged and performed during that time,” Carmen notes.

The Fields musical legacy continues. Carmen’s brother Ernie Fields Jr. is a highly successful West Coast musician and studio and TV contractor who has worked with Stevie Wonder and Aretha Franklin as well as on the shows “American Idol,” “The Voice” and “X Factor.” His grandson, Ryan Brown, is a Boston keyboardist who plays with Louie Bello, Melissa Bolling and Athene Wilson among others.

“Books like this are important,” says Brown, because they “preserve and honor the work, careers and stories of the musicians that laid the foundation — like my great-grandfather and my grandfather. Their success came at a great cost and sacrifice. They endured several challenges being out on the road as Black musician. But with their talents, love for music and skills as businessmen and leaders on and off the stage, they were able to overcome those obstacles.”

At a recent gig, Brown gave a copy of “Going Back to T-Town” to his bandmate “Sax” Gordon Beadle, the internationally touring Cambridge jazz and blues honker and longtime Ernie Fields fan. “The book is a chance to learn about a lot of history that flows right alongside more well-known stories and, in the end, gives us a bigger, better and clearer understanding of jazz, R&B, early rock-and-roll, and the life of those who created this big beautiful world of music that’s easy to take for granted,” Beadle says.

Carmen Fields will be reading from and signing “Going Back to T-Town” on Thursday, Feb. 1 at Belmont Books in Belmont and Friday, Feb. 2 at Frugal Bookstore in Roxbury.