Advertisement

The Davis Museum celebrates the multiplicity of Lorraine O'Grady

Artist Lorraine O'Grady has lived many lives. "Both/And," a retrospective of her work now up at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, explores the art O'Grady has produced across the decades.

A central theme in her work is captured in O'Grady's essay “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” written in the early 1990s. She probes the relationship between the Black female body and art. “It's true, 'both: and' thinking is alien to the West,” she wrote in the essay's postscript. “The greatest barrier I/we face … is the West's continuing tradition of binary, 'either: or' logic.” Binaries define us, before we even have the privilege of self-expression. It is a mode of categorization that so often results in the establishment of the normative — white, male and Western.

O’Grady instead offers a “both/and” framework that gestures toward a reality where identities, both old and new, mutually coexist. It’s a fitting name for the retrospective, originally organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 2021, which features works made by O’Grady throughout the decades that explore the revolutionary potential of eschewing and resisting categorization.

“O’Grady argues that with ‘Both/And,’ we can hold supposed binaries together,” said Amanda Gilvin, senior curator and assistant director at the Davis Museum. “We can see how they’re not actually different … but interrelated.” The rough, messy parts where the edges of things overlap are sites of creation for O'Grady.

The retrospective coming to Wellesley is a special moment — O’Grady graduated from the college in 1955 with degrees in economics and Spanish literature. In 2010, she donated her papers to Wellesley. To commemorate the opening of “Both/And,” the college is hosting a series of free performances. O'Grady's works will also be studied across multiple departments. Professor Nikki A. Greene, who teaches art history at Wellesley, is leading a seminar titled "Lorraine O'Grady, '55: Writer, Artist, Archivist." “My students see themselves in Lorraine,” she said. “To graduate from here as one thing … and then she’s off into the art world. I think it opens up a world of possibilities for them.”

Born in 1934 in Boston to Jamaican immigrants, O’Grady has lived a life of “both/and." In an interview with ArtForum in 2021, she describes herself "as someone who’d spent my life on the hyphen between Caribbean and American." She grew up in Roxbury and attended what was then Girls' Latin School (now the Boston Latin Academy) before heading to Wellesley College. She’s had a number of different careers, including rock critic, professional translator and intelligence analyst for the government. Most would say that O’Grady entered the art world later in life (she was in her 40s when she staged some of her first performances), but O’Grady would probably argue that she was an artist all along.

Advertisement

“Both/And” shows us a generous and comprehensive slice of O’Grady’s oeuvre that includes photo installations, collage and video. One of O’Grady’s most famous works, “Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire,” was created just as she was breaking into New York’s art scene. In 1980, she staged a guerilla-style performance at the gallery Just Above Midtown, showing up as an aging beauty queen wearing a dress and cape made up of 181 pairs of white gloves.

She carried a whip covered in chrysanthemums, which she used to hit herself, and recited poetry from French-Guianese writer Léon-Gontran Damas. “O’Grady describes the gloves as symbols of internalized oppression and the whip as a symbol of externalized oppression,” said Gilvin. “The whip was really invoking this dangerous violence that continued to shape the segregation she found in the art world.”

O'Grady's character was meant to be a critique, not just of the institutions siloing Black artists, but of colonialism itself. There’s also a subtle jab thrown at Black artists too scared or too comfortable to upset the status quo. “O’Grady had many successes in different fields but it was when she became an artist that she describes being blocked in more than she ever had before,” said Gilvin. “Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire" would subsequently be shown at the New Museum in 1981.

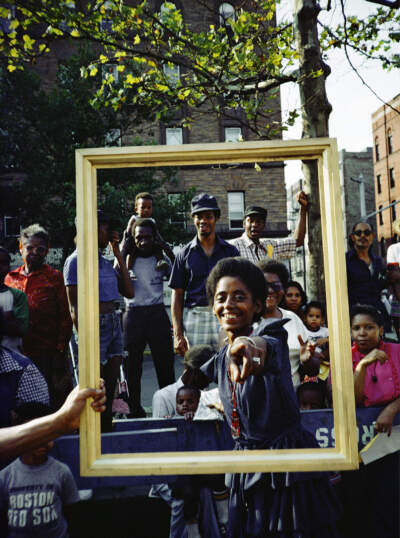

The racism she observed in the art world led O’Grady to continuously explore the intersections between Blackness and art in her work. “Art Is” was a public art performance that took place in Harlem a few years after she debuted "Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire." “A Black social worker told her … that avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with Black people,” Galvin explained. “Well, O’Grady proceeded to stage ‘Art Is’ at the African American Day Parade.”

A float bearing a massive golden frame rolled down the streets of Harlem as performers and dancers, holding smaller golden frames, jumped off the float and interacted with the crowd. Photographers captured the scene. “The people in the crowd…they understand themselves as being worthy of being art,” says Nikki Greene. “[Art] doesn't have to be Midtown. It doesn't have to be LA.” Seeing a Black neighborhood, and its Black and brown residents, captured within a frame, was a subversive act that challenged mainstream conceptions of what “art” is while emphasizing that art lives in the moments of everyday life.

Blackness as art is also examined in “Miscegenated Family Album," a series of diptychs. Miscegenation is the mixture of people from different ethnic groups or racial backgrounds — O’Grady herself is a product of miscegenation, as are many Black people throughout the African diaspora. In this series, O’Grady juxtaposes photos of Egyptian figures with pictures of her family, namely her sister Devonia who passed away in 1962 at the age of 38.

“[O’Grady] writes of an experience as a third grader,” said Gilvin, “in which a teacher pulls down one of those old fashioned maps right from the wall and says, ‘Children, this is Africa. Except for this upper right corner, that is not Africa. That is Egypt.'”

For so long, Egypt has been positioned as separate or different from the rest of Africa. But when she was working for the government, O’Grady visited Egypt and was often mistaken for being Egyptian herself. This, along with her experiences in school, led O’Grady to explore the connections between Egypt and the African diaspora. What O’Grady does with her diptychs is challenge popular perceptions of Egypt and instead points to the intimate ties that exist between Black people across the world, regardless of nation or origin.

At the age of 89, O'Grady is still not done creating. "Announcement of a New Persona (Performances to Come!)" from 2020 showcases a new character — a knight in armor with headgear comprised of tropical greenery. "She is engaging with multiple histories," said Gilvin. "She's particularly interested in European chivalric traditions... as well as looking at the African diaspora and the relationships between African masquerades and Caribbean Carnival." Once again, O'Grady uses her "both/and" framework as a vehicle to examine Blackness and legacies of colonialism.

While “Both/And” certainly contains pieces that are critiques, like "Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire," it is also much more than that. We see O'Grady and Blackness as both the artist and the subject. We see O'Grady go beyond the critique and firmly into the realm of making. As O’Grady wrote, towards the end of "Olympia's Maid," “critiquing them does not show who you are.”

Instead, she has crafted her own world that does show us who she was and who she is becoming, in all of her multiplicity and nuance.

"Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And" runs at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College through June 2.