Advertisement

Massachusetts health officials will spray pesticides to address mosquito-borne illness

Massachusetts public health officials are announced they will spray pesticides two counties starting this week to address the elevated risks of mosquito-borne illnesses this year.

They’re concerned about eastern equine encephalitis. The state Department of Public Health announced last week a man in his 80s had caught the disease, the first human case found in Massachusetts since 2020.

The town of Plymouth announced Friday that it's closing public outdoor recreation facilities from dusk until dawn each day after a horse in the town was infected with the disease.

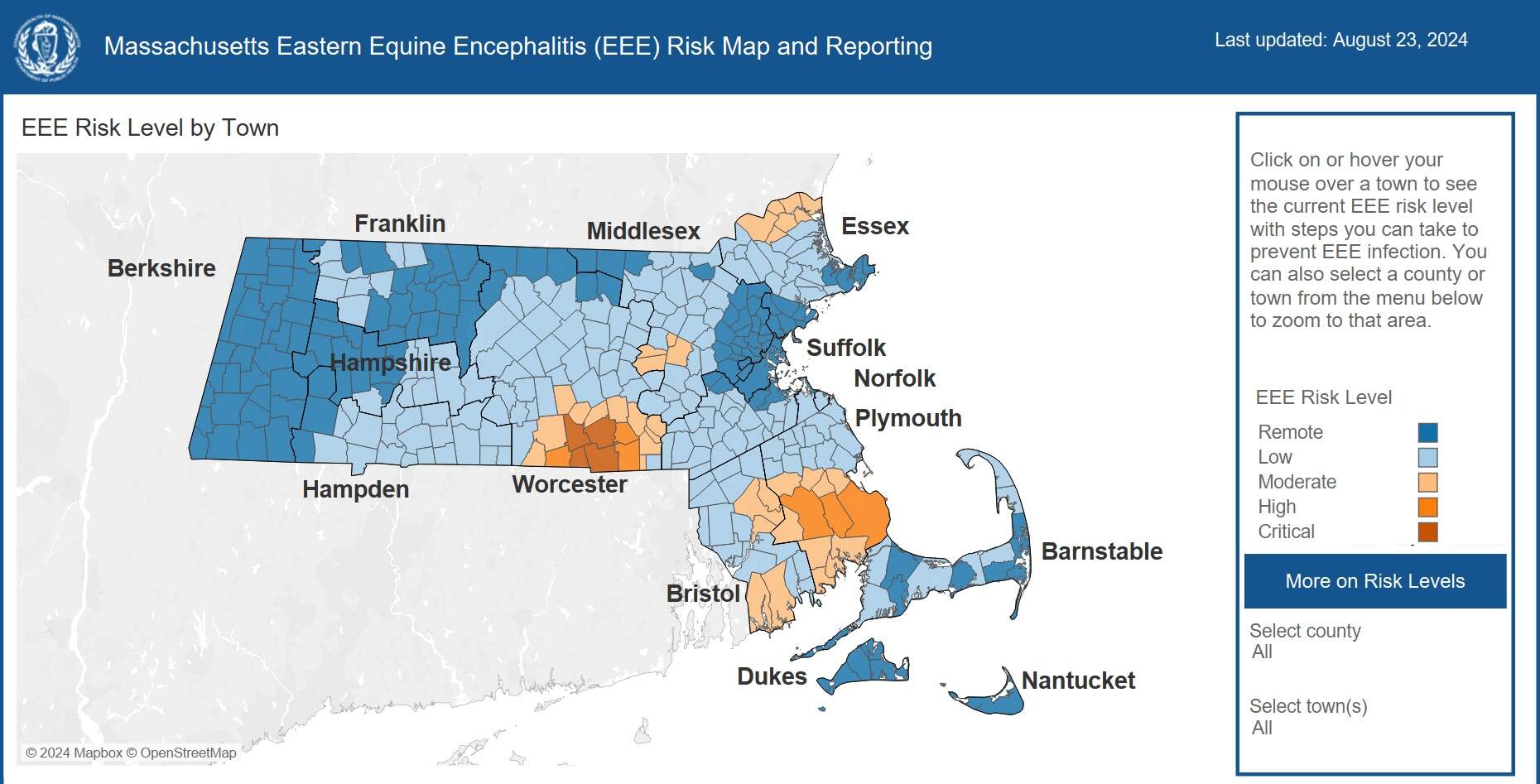

Meanwhile, state health officials warned that a cluster of four towns south of Worcester — Douglas, Oxford, Sutton and Webster — are at “critical risk” after a man from Oxford caught the virus.

The spraying will take place at night, starting shortly after dusk and ending in the early morning. DPH said more details would be available on its website. The aerial spraying zone includes Carver, Halifax, Kingston, Middleborough, Plymouth, Plympton, Rochester and Wareham. The truck-mounted spraying zone covers Douglas, Dudley, Oxford, Sutton and Uxbridge.

The state uses the EPA-registered pesticide Anvil 10+10 for mosquito spraying, applying it using an ultra-low volume aerosol that public health department said uses small quantities of the chemical. The department said people with known sensitivities or respiratory conditions like asthma should stay indoors during the spraying, though "it is unlikely a person would be exposed to amounts that would cause adverse health effects."

It is considered safe to eat food grown in areas where Anvil 10+10 is sprayed, and animals do not necessarily need to be brought indoors, the health department said. But anyone who owns a small ornamental fishpond in the aerial spray area should cover it during the night of spraying and beekeepers are encouraged to consider applying a cover to hive exits to prevent bees from direct contact during spraying.

The packaging of Anvil 10+10 has been associated with harmful per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of man-made chemicals that do not break down entirely in the environment, and exposure to their long-lasting presence has been linked to serious and negative health impacts. PFAS was found to leach from packaging into Anvil 10+10, creating thorny problems for some communities.

Advertisement

Along with spraying, state and local health officials urged people in those towns to avoid the peak mosquito biting times by finishing outdoor activities by 6 p.m. until Sept. 30 and then by 5 p.m. after that, until the first hard frost.

They also recommend that people across Massachusetts use mosquito repellents when outdoors and drain any standing water around their homes.

Jennifer Callahan, Oxford's town manager, wrote in a memo that the family of the man who caught the virus in mid August had reached out to her office.

“They want people to be aware this is an extremely serious disease with terrible physical and emotional consequences, regardless if the person manages to live,” Callahan wrote.

She said the infected person had often recounted to his family how he never got bitten by mosquitoes. But just before he became symptomatic, he told them he had been bitten. She said the man remains hospitalized and is “courageously battling” the virus.

Callahan said the family is urging people to take the public health advice seriously and to do their utmost to protect themselves.

The presence of the virus in Massachusetts this year was confirmed last month in a mosquito sample, and has been found in other mosquitoes across the state since then. In a 2019 outbreak, there were six deaths among 12 confirmed cases in Massachusetts. The outbreak continued the following year with five more cases and another death.

There are no vaccines or treatment for EEE.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that although rare, EEE is very serious and about 30% of people who become infected die. Symptoms include fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea and seizures.

People who survive are often permanently disabled, and few completely recover, Massachusetts authorities say. The disease is prevalent in birds, and although humans and some other mammals can catch EEE, they don't spread the disease.

The CDC says only a few cases of EEE are reported in the U.S. each year, with most infections found in the eastern and Gulf Coast states.

With reporting from Nick Perry of The Associated Press and State House News Service's Colin A. Young.

This article was originally published on August 26, 2024.