Advertisement

A Canadian Family's Dangerous 12K-Mile 'Paddle To The Amazon'

Resume

On the morning of June 1, 1980, Don Starkell and his two sons climbed aboard Orellana, their orange, custom 21-foot canoe and launched on the Red River from a park near their home in Winnipeg. As they paddled off, Don made an announcement.

"All aboard for the Amazon Hotel."

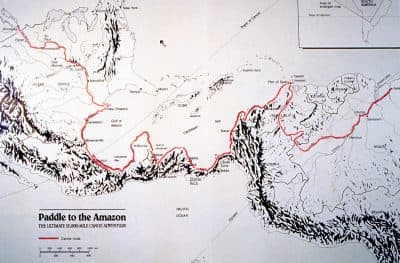

The Amazon Hotel was a seedy flophouse on the outskirts of town. Friends and family members present at the launch might have laughed because they expected the Starkells to give up by the time they got there. Or, they might have laughed to hide their fear. Because the Starkells’ plan was to paddle 12,000 miles from Winnipeg to Belém, Brazil, on the mouth of the Amazon River.

'We'll Paddle Right Outta Winter'

It was a crazy idea. But it began innocently enough.

"I told my dad when I was 7 years old," Don's older son, Dana, begins, "I said, 'Dad, you know what I wanna do one day? I wanna walk to the jungle and be like a monkey, you know?

"Next thing you know, he was getting out books and researching rivers and connecting routes together. And it was a couple years later, when I was 9 years old, that he came up to me and he said, 'Dana, how would you like to get in a canoe one day, and we’ll paddle so far south, we’ll paddle right outta winter?' You’ll start to see snakes and parrots and monkeys hanging from the trees.' And I’m like, 'Yeah, monkeys. That’s like what I wanna be.'"

Don Starkell spent the next 10 years planning a route. He estimated the trip would take two years.

Many thought Don and his sons were nuts.

"On my mother’s side, my aunts and uncles, most of them, were basically saying, 'You’re crazy,'" Dana's younger brother, Jeff, says. "'You’re gonna die.' All this kind of stuff."

Jeff was only 18 and had planned to study electronics in the fall. He had serious doubts about going. Dana, 19, was a guitarist in a working rock band, more of a dreamer, and more apt to follow his nose for two years.

The trio looked chipper and healthy as they launched on the Red River. But there was a lot going on in their heads.

"You know, I was leaving a lot behind in terms of friends and all the rest of it," Jeff says.

(Including a girlfriend and a really cool muscle car.)

"But probably the strongest emotion was just, 'What the heck are we doing here?'" Jeff recalls.

"You know, I knew that we were going to be gone for a long time, but I certainly had no comprehension of the distance or all the dangers that were ahead," Dana says. "My dad did. He was in a whole different head space than we were. My brother and I, we were going off to this big adventure, and my dad felt like he was going off to his execution."

So why go?

Don's Difficult Past

Don Starkell’s love of canoeing came out of a childhood filled with neglect and abuse. When he was 6, a judge gave him the choice of returning home or moving into an orphanage. He chose the orphanage. But when he was 10 years old, Starkell discovered a canoe owned by a foster family. He took to paddling in the creek that ran behind their house. There, he felt free, independent and in control for the first time in his life.

In 1950, Winnipeg was almost totally inundated by the flooded Red River. Starkell, by then a teenager, paddled to neighbors’ houses, delivering bread and milk. Later, he competed in hundreds of outdoor canoe races.

To The Mississippi And Gulf Of Mexico

A month into their journey, Don and his sons reached the outskirts of Minneapolis and entered the world’s fourth longest river.

"The Mississippi was just a ton of fun in a lot of ways," Jeff says.

"People pretty much put out the red carpet for us everywhere we went," Dana adds.

Boaters delivered beer and soda. Some of the locals treated them to home cooking or hearty meals at local restaurants. The Starkells felt they had been absorbed into the culture of the Mississippi. And they loved it.

Seven hundred miles later, they reached New Orleans, where they joined the Intracoastal Waterway, a series of inland canals protected from the Gulf of Mexico’s fury. Overall, the trip was going well. But Jeff began to sense that his father was

concerned about something.

"I don’t think my dad was ever supremely confident that we would be able to do the Gulf portion of the trip," he says. "My sense was that he was quite worried. That he was sort of trying to put up a brave face to us, saying, everything will be fine' kind of thing."

Don Starkell had some experience paddling in the ocean, but only in waters protected from wind and wave. His sons had none.

The Starkells left the Intracoastal Waterway, paddling out of Port Isabel, Texas, and into the Gulf. After a few miles in Mexican waters, waves crashed over the sides of the canoe, which began filling with water. It was nearly impossible to paddle. They headed for shore, but they weren’t sure how to land the canoe.

"My dad says, 'Well, I think what we should do is, we’ll get in front of this wave, and we’ll paddle as fast as we can, right?'" Dana recalls.

Which is probably the best thing to do ...

"Which was the worst thing to do," Dana continues, "because we’d just ended up surfing like a surfboard. A wave came up behind us, we took off like a rocket, and the front of the canoe dug in, the whole canoe went catapulting head over heels. I was OK. I was right in front of the canoe. But my dad went 'Ahhhhhhh,' sailing through the air."

The Starkells struggled day after day to launch from shore. They tipped dozens of times before figuring out a reliable method. And heavy seas along the coast of Mexico slowed them down. Their food and water dwindled. If their progress remained poor, they’d run out before they reached the next small city a couple hundred miles to the south.

And then they got an idea: Why not navigate Laguna Madre? That’s a shallow inland

lagoon protected for over a hundred miles by a series of barrier islands. That would be an easier paddle, right? And it was, until ...

"All of a sudden we notice the water’s getting shallower and shallower, and there’s not really an opening to the Gulf," Jeff says. "There’s not an easy way to get back."

Laguna Madre is accessible only by two inlets many miles apart. But the Starkells’ maps didn’t show that.

"So we were paddling along, and at some point the water became too shallow to paddle in," Jeff says. "So we got out and started walking, dragging the canoe through the water."

"Like 6, 7 inches of water for miles and miles. Cut up our feet and everything," Dana says.

"And then at some point there was just no water at all," Jeff says. "And then we were pushing through this slimy mud.

"It got to the point where every time you’d take a step, your foot would sink maybe an inch, and this boiling hot, muddy water would pour over your foot. It was just pure pain every time your foot went in."

'We Decided The Trip Was Over'

The canoe was now totally stuck, with miles of mud on all sides. Only two gallons of drinking water and a little bit of food remained. They were baking under the blazing sun with no chance of hauling the canoe back to the Gulf. Don and Jeff left Dana with the canoe and walked for seven hours to the small coastal town of La Pesca.

There, they purchased food and water and hired a driver to meet them. They lugged the supplies back to the Orellana. After a miserable few days, they managed to dislodge the canoe and carry everything through the hot sludge to the road. Their driver showed up and drove them into town, where they’d keep an eye on the sea and wait for better conditions.

"But the waves were coming in so strong we couldn’t launch the canoe," Dana says. "And my dad felt there was no way we were ever going to be able to paddle on the Gulf. We decided the trip was over."

The Starkells had already accomplished something nobody else had: paddling a canoe from Canada to Mexico. They decided to stay in the relatively cushy city of Veracruz and become men of leisure for the winter. Or maybe longer.

"My dad said, 'You know, you can go back home if you want. Or you can stay here and play guitar for a couple years,'" Dana recalls. "I said, 'I’ll stay here and play guitar.'"

Jeff Leaves The Voyage

There was some talk of resuming the trip in the spring. But by November, Jeff was getting antsy.

"I felt like, I really don’t want to abandon my brother and my dad," he says. "But on the other hand, I’m feeling like life is passing me by. I wanna get on with my education. And so I decided to head back to Canada."

On Nov. 6, 1980, Jeff flew back to Winnipeg.

"It was terrible. When Jeff left, we didn’t even know if it was possible to paddle the canoe with two people," Dana says. "Without Jeff, I was thinking, 'How on Earth are we ever going to do this?'"

Dana played his guitar for a couple months while Don snorkeled. They considered abandoning the voyage for good. But the weather improved, and on Feb. 20, 1981, eight months into their voyage, Don and Dana resumed the trip. A couple months later, they were around the Yucatan Peninsula, out of Mexico and into Belize.

Tropical Storm Arlene

Local fishermen there advised them to paddle several miles out to a series of barrier islands, where it would be safer going. On May 5, they decided to camp on a

small, picturesque island a few miles off the coast. Everything seemed fine.

"And that particular night it was glass calm," Dana says. "But my dad sort of had a sixth sense about things. He went over to the canoe and he tied up the canoe as though we were gonna get hit by a hurricane. He just...I don’t know. Maybe it was just too nice out or something, you know?

"And there was a little tiny, like, a fishing shack on stilts. We fell asleep just right on the wood floor there. And in the middle of the night my dad woke me up. He says, 'I was listening to the radio, and the station just went dead.' There was a kind of a hatch on this shack. He said, 'Lift up that hatch and see if you can see anything.' And I looked out and all I could see was a black wall coming toward us."

It was Tropical Storm Arlene. Getting stranded miles from the Belize coast without a canoe or supplies? That could be the end of more than the voyage.

"The wind started picking up — it blew the waves right over the whole island," Dana continues. "We were so scared. We didn’t know what to do. My dad tried to open up the front door to look at where the canoe was. He couldn’t even get the door open, the wind was so strong. And so, eventually, we just laid down there during the storm and went to sleep.

"And in the morning, it was peaceful again. But we figured our canoe was gone, for sure. We opened up the door, and the canoe was just sitting there, floating."

Don had tied the canoe to a mooring using 20 knots. Exactly one had held.

Held At Gunpoint In Honduras

While Don and Dana navigated the Central American coast, Jeff was studying back in Canada. He followed their journey via the occasional phone call or postcard.

The voyagers began to quarrel. They suffered from sunburn, biting insects and salt sores. But their worst ordeal was still ahead of them.

They’d been warned of pirates, drug runners and soldiers in Honduras and Nicaragua. They’d been harassed a few times, mostly without incident. Then, one day, they stopped to rest at Laguna Caratasca on the Honduran coast. They befriended two local women who offered to prepare a meal.

"So I sat down on this big coconut tree and started practicing guitar," Dana says. "My dad is walking around with a machete collecting up coconuts. And while I’m practicing guitar, these two guys come along, and they start talking to my dad."

Don spoke passable Spanish.

"And then they left, and my dad walked over to me, and he said, 'You know, Dana, those two guys I was just talking to, they’re quite concerned that we’re going to get robbed here. That where our canoe is, it’s not safe. That we should haul it back towards where these thatched roof houses are.' We weren’t interested in doing that. We weren’t that concerned about anybody stealing our stuff, really, at that point."

The allegedly good Samaritans returned a couple hours later.

"And this time one guy was on a white horse, and the other guy had a big shotgun," Dana says. "And they come marching up to us. Raised the shotgun just slightly above our heads and blasted off. Start screaming at us that now we’re going to listen to them, and we’re going to move our canoe."

It was at this point that Don and Dana realized these men were actually rogue Honduran soldiers. Dana thinks he now knows what they were planning.

"The whole reason they wanted us to move our canoe up there was that they wanted to steal our stuff from us, but they didn’t want to have to carry it up there," he says. "They wanted us to carry it there for them first, you know? But to keep this stuff, they figured they’d have to kill us. So their plan was they were gonna walk us 7 miles down this road there in Honduras and execute us.

"So now the sun is starting to go down. They tie us up a little bit, and they start marching us down this road.

"We’re trying to think, 'How can we get out of this predicament?' We started filling their heads as much with lies as we could, saying that we were on this big expedition, the United States Army knew exactly where we were, they’re following us, they had helicopters, if anything happened to us they’d come in there and blow everything up."

That plan seemed to work. Instead of leading them into the jungle, the soldiers marched Don and Dana 7 miles to an army base, where they were interrogated and released. Dana wondered how and why they had been spared. Had tall tales saved their lives?

"The crazy thing was, these two women that we had befriended earlier, they told these two soldiers, they said, 'If you kill them, we’re going to report you.' And they put their lives on the lines for us, because we had just been friendly to them for 15 minutes."

'Absolute Peace'

The Starkells got out of Honduras as quickly as they could. They paddled past Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia. In Caracas, Venezuela, they befriended a banker and his family. For three days, Don and Dana stayed in their luxurious home, where they enjoyed fine meals, rest and time for reflection. Dana, as always, played guitar. Don updated his audio diary. This is one of the few recordings that survived the frequent capsizing and thefts along their journey.

Had a lot of funny problems. Had a lot of hassles from police and officials and idiot people that won’t leave us alone. But things are good. We’re happy that we’re on the trip. We’re happy we’re where we are right now. And I don’t think ever in my life I’m going to be sorry for taking the trip, because it’s been just an incredible learning experience.

The duo detoured to Trinidad and Tobago for another extended rest. Then they paddled in the ocean for the last time and reached the delta of the Orinoco River.

"The day that we left that big massive bay there from Trinidad and entered those little tributaries, I mean it was just such a feeling of peace," Dana says. "Absolute peace."

"Their plan was they were gonna walk us 7 miles down this road there in Honduras and execute us."

Dana Starkell

They were overjoyed to leave Central American war zones and the dangers of Colombia for an inland landscape featuring jungle and shade.

"And we’re going along on the river one morning and just, boom, out of nowhere, this giant dolphin jumps right out smack in front of me," Dana says. "Comes completely out of the water and down. Solid pink. And so I said, 'Dad, did you see that?' It’s like, 'What the heck was that?'"

It was a tonina, a freshwater dolphin that schools in South American river basins.

"They loved to follow us, but they’re kinda shy," Dana says. "It’s hilarious."

After two months paddling upstream on the Orinoco, the Starkells joined Rio Negro, where they saw lots of monkeys and snakes and crocodiles, the animals of Dana’s childhood imagination. They subsisted on bananas, coconuts and the occasional paca, a large rodent weighing up to 15 pounds. They slept and ate in ramshackle huts of the families who lived along shore. They learned that some of the poorest people in the world were also the most generous. Families who had close to nothing were often willing to share everything they had.

"The only real problems we ever had were with humans," Dana says, "but 99 percent of the people we met were so good to us, you know?"

The Amazon At Last

On March 31, 1982, Don and Dana finally entered the Amazon River, which met all of Dana’s expectations as a lush junglescape, right?

"Not a bit," he says. "Not even close. I would say the No. 1 animal that we saw on the Amazon was actually a cow. You kinda come around a sweep of the river, and think maybe here you’ll see a crocodile or something, and there’s a big cattle ranch. You know, the last 1,000 miles is more like a big inland ocean. It’s massive."

The Amazon was in spring flood, and they paddled downriver with ease, thinking, "We’re really going to make it."

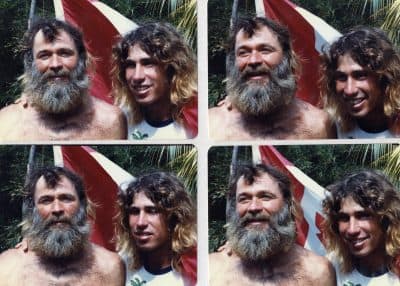

Exactly 23 months after departing Winnipeg, Don and Dana Starkell glided into Belém. They had accomplished the goal many had called impossible. They had covered 12,182 miles. It should have been a moment of triumph and celebration. But ...

"For two solid years, every single day when we woke up, we had this goal and a purpose," Dana says. "And coming into Belém, as happy as we were to know that, you know, you’re safe, you’re alive — that was a beautiful feeling. But there was definitely a huge sadness in the sense that the trip and the adventure itself were over, you know?"

Dana and his father wandered around Belém for a couple days, feeling aimless and lost. Then they made their way home. First by freighter, then by rental car. They drove to Grand Forks, North Dakota, where Jeff met them with the family’s familiar red Datsun.

"He was scared of us," Dana says of Jeff, laughing.

"They just had this look to them, almost like wild animals," Jeff says. "They looked like trouble."

"And this is, now, we had been living on the ship for over a month," Dana says. "And we were all cleaned up and everything. And we felt like we were really civilized again."

Dana says it was probably harder for friends and family back home to make the adjustment to their return than it was for them to resume their former lives.

"Coming back to Canada was like the easiest thing in the world," he says. "All I did was just lock myself in the house, and didn’t want to go out very much."

Lessons Of The Journey

So what is the lesson of the Starkells’ voyage? And why did Don Starkell subject his sons to the possibility of malnutrition, thirst, drowning and summary execution? I am as disturbed by this story as I am attracted to it. But Dana says that hidden within the apparently insane voyage was a gift his dad had never fully articulated.

From the outset, it had been one of the Starkells’ goals to learn as much as they could about the people they met and about human nature.

"You grow up in Canada or the United States, it’s impossible to have a perspective of what you’ve got," Dana says. "It just is. It’s not until you live in the Third World, actually live in people’s homes with them, day after day after day, and you’re hungry yourself, and you go through all these things, that you can truly kind of look at what you’ve got and really appreciate it."

Some have criticized Don Starkell and his frantic miles-at-all-cost method, claiming it’s impulsive, risky and downright perilous. But ask his sons about him, and they’ll paint a portrait of a man who, though at times self-centered and recklessly driven, was also thoughtful and generous.

"I have so much respect for my father, I can’t tell you," Jeff says. "I always will. I think about him all the time and miss him."

Don Starkell died in 2012 after a battle with cancer. He was 79.

Jeff now lives in Ottawa. Dana’s a classical guitarist living in Iowa. They still take canoe trips. Much shorter ones.

From time to time they visit the little Winnipeg park where they began their voyage to the Amazon. There, a bronze plaque commemorates their journey, ending with the words:

"This incredible adventure in spite of all odds has been recognized as a world record for the longest journey ever made by canoe."

Learn more about the Starkells' journey in Don's book, Paddle To The Amazon, and in an documentary based on that book. Dana's story about meeting Queen guitarist Brian May is here.

You can view the Orellana, the family's canoe, at the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough, Ontario.

This segment aired on October 7, 2017.