Advertisement

The Athlete Who Was Granted An NCAA Medical Waiver For Addiction

"To me, it's not even close to just a game," Jon Cross says. "This is my family's culture. This is what we love and do and talk about and grew up bonding, playing together."

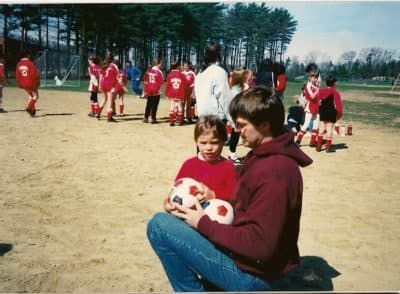

For Jon and his family, the sport that’s so much more than a game is soccer. It started with his oldest sister, Megan.

"Wearing the No. 9 as a jersey — and then my brother did the same thing, my sister Niki did the same thing," Jon says. "And we, kind of, all just followed each other’s footsteps."

Jon grew up in Pembroke, Massachusetts, a town of less than 20,000 about 30 miles south of Boston. The soccer-playing Cross siblings were written up in newspapers and magazines. The three oldest played Division I in college. Niki turned pro. Jon was the youngest.

"It was a lot of pressure, I’m not gonna lie," Jon says.

Growing up, Jon always assumed he’d keep following in his siblings’ footsteps. But his dreams would be derailed. And it’s not like he didn’t know any better.

"I grew up with 'Just Say No,' " Jon says. "I got horror stories my whole life. And my generation grew up to be the worst heroin epidemic of all time."

That epidemic is important to Jon’s story. Because along the way, the NCAA —an organization usually not known for being flexible and forward thinking — would be asked a pretty tough question: if drug addiction is a disease, as most doctors agree that it is, should a season missed due to drug addiction be counted the same way as a season missed due to a torn ACL?

That might seem like a crazy question at first. But let me tell you the story from Jon's perspective.

Addiction

Jon’s addiction has roots in junior high. He’d go into the woods to drink and smoke pot. He started taking Adderall. He says he wasn’t much different from other kids in his area — kids who didn’t become addicted to drugs.

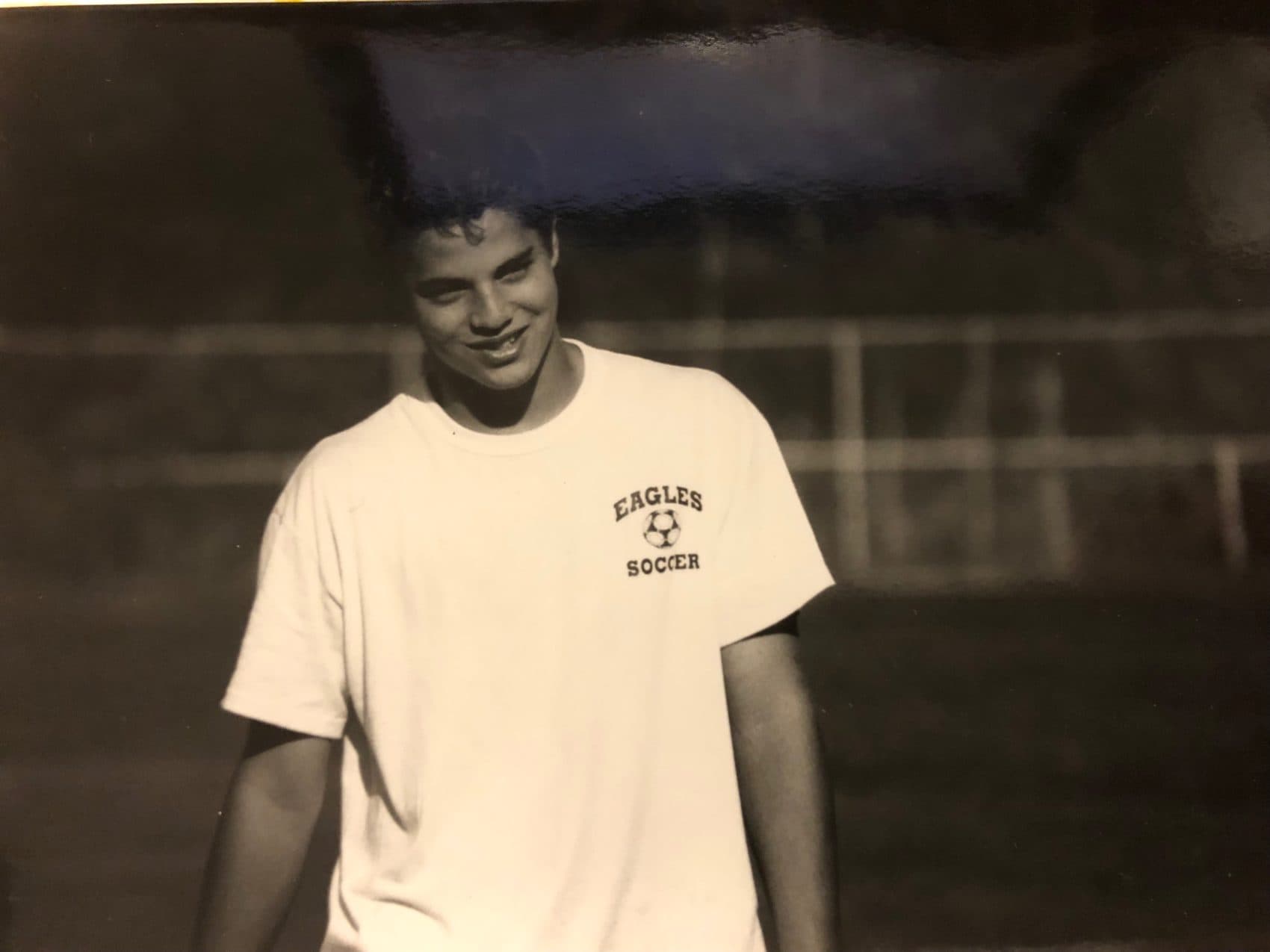

He says his addiction got to be a bigger issue his junior year of high school.

"I was one of the better kids on my high school soccer team. And I couldn't stop smoking weed," he says.

Jon was missing classes. So his coach told him he’d have to sit out for one practice. Instead, Jon quit. He never played high school soccer again. His parents were disappointed — especially his mom.

"As much as you want to think that all these sports and games are for you, they put so much effort into me," Jon says. "She put so much time going to practice, showing up to my games. For me to just throw it away my junior year in high school was kind of a slap in the face."

Jon moved to Florida for college, but he was still drinking and doing drugs — and without soccer to anchor his identity, he took on a new one: a tough guy from Boston.

"I use to lie about being from Boston," Jon says. "I'm not from Boston. I'm from Pembroke."

Advertisement

Jon thought a change of scenery and a return to the sport he loved would turn things around. So he moved back to Massachusetts, enrolled in UMass Boston and walked on to the soccer team.

'I Might Have A Bit Of A Problem'

He knew that as an NCAA student-athlete, he'd be subjected to random drug testing. So …

"I went on this website called, PassYourDrugTest.com," Jon says.

Jon was looking for a way to keep doing drugs without failing a test. The website suggested opiates and cocaine, because those drugs leave your system relatively quickly. So that’s what Jon did.

But it wasn’t a drug test that derailed Jon’s first season at UMass. One day, after being out partying all night before a game, he just called the team captain and quit.

Somehow, Jon convinced the coach to let him back on the team the next year.

"At this point though, my opioid abuse was really bad," Jon says. "So I showed up to practice every day high. And I knew they were drug testing people — they drug tested a friend of mine — I just felt like it was coming."

Jon says, to save himself and his family the embarrassment of a failed drug test, he quit again. Though he did manage to graduate … barely.

"I guess I'll just be honest. My senior year, I paid people to write my papers," Jon says. "I'd say, ‘I'm an economics major, supply and demand. I have the money, they want to write papers. Boom. I must've learned something.’ "

Jon’s graduation, as illegitimate as it might have been, is important to this story. Because he hadn’t used up all of his NCAA eligibility. But in Division III, eligibility ends at graduation.

The NCAA does make exceptions. But it would be another few years before Jon was in any shape to challenge the system.

"My drug use was already at a limit where, if I had stopped taking them, I'd get sick," Jon says. "So I started working in finance in Boston, getting high every day in the parking lot. And that's where I started realizing that, like, I might have a little bit of a problem."

Jon tried another change of scenery. He moved to California. But ...

"Surprise, surprise," Jon says. "They had plenty of drugs in San Diego."

'Is This Your Life Now?'

Before long, Jon was back in Massachusetts. He started taking regular trips down to New York City where he says a “crooked doctor” gave him prescriptions for hundreds of Percocets at a time.

"Then I would get on the bus. I would bring them back to Massachusetts," Jon says. "And I remember, I had moments where I'd look out the window and be, like, ‘Is this your life now? Is this what you're doing? Are you just going to sell drugs? Are you ever going to, kind of, snap out of this?’ And then I'd say, ‘Of course I am. This is just a phase.’ "

Jon started shooting heroin. Months passed. And then one day in May of 2014, a friend who’d been sober for years stopped by to check on him.

"He sat down and he said, ‘Jon, how's it going man?’ I said, ‘Good.’ He said, ‘Really?’ I said, ‘No.’ "

Recovery

The next day, Jon Cross checked into rehab. He was told he needed to re-evaluate his entire life and how he looked at things.

"Like, I thought I was going to be able to pet some horses and, you know, do some yoga and maybe you'd feed me some organic greens, and I would go home," Jon says.

In truth, yoga and meditation played an important role in Jon’s recovery.

While he was in treatment, Jon called his friend, the one who had gotten sober years earlier.

"I said, 'You think everybody at home knows I'm a drug addict? I'm really nervous about everybody finding out,' " Jon recalls. "He says, 'Yeah, man. The funny thing about that is: you're usually the last one to find out.' "

After rehab, Jon moved to Portland, Maine.

That’s when he realized: he missed soccer. He missed everything about it.

He thought maybe he could coach or consult with a team.

"I emailed a bunch of local coaches," Jon says. "And I said, ‘Hey, this is my story. I don't want any money. I don't want anything else. I just want to be a part of the game.’ "

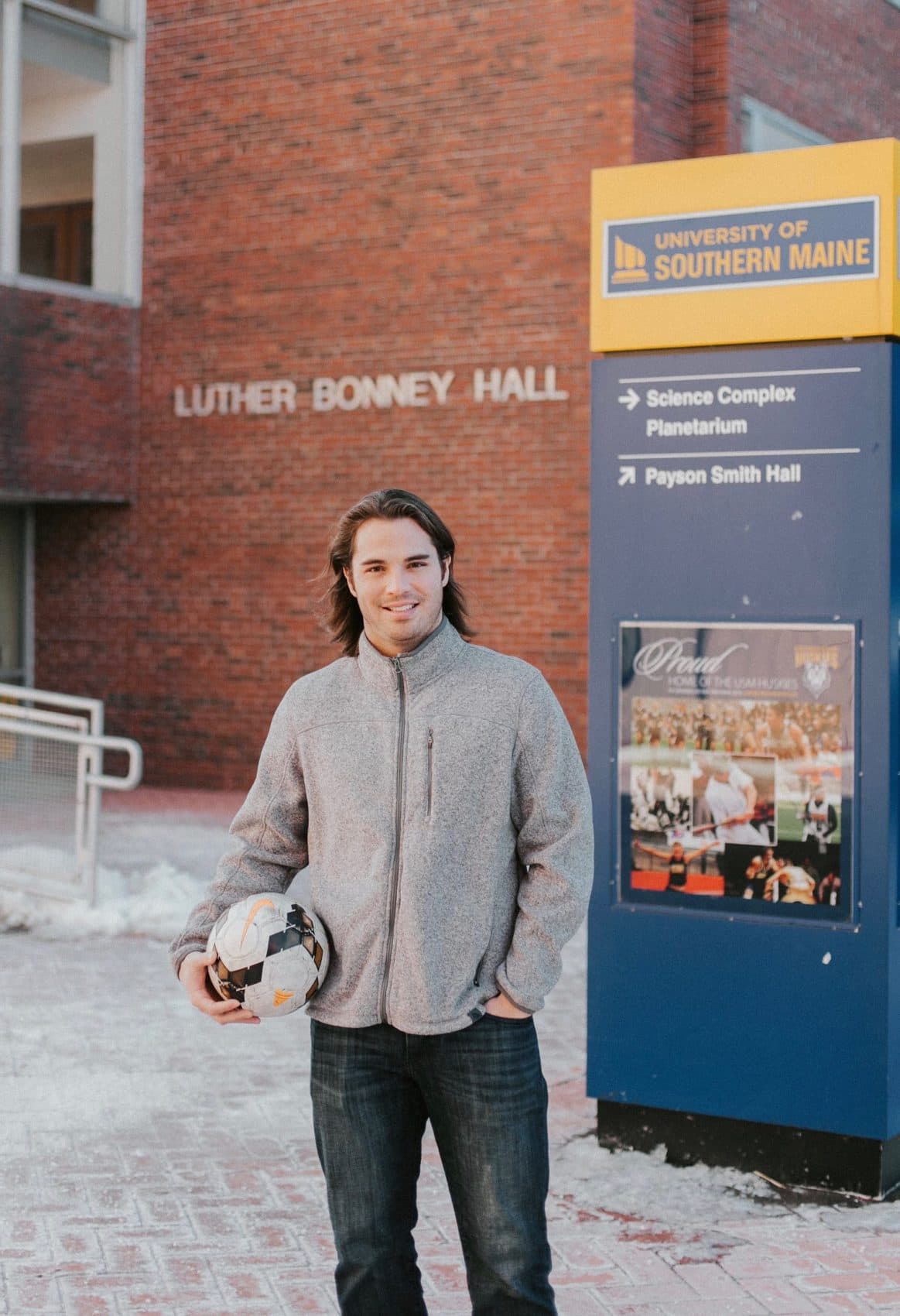

He got one response, from the head coach at the University of Southern Maine. But Jon hadn’t as much as touched a soccer ball in two or three years. So before he showed up to the interview...

"I went out to a park, and I went up to a bunch of people," Jon says. "I was the only kid that spoke English. And I said, ‘Can I play?’ And they said, ‘What?’ And I just raised my hand and they passed me the ball. And then I started going down there every single day."

Jon was invited to help out with the team at Southern Maine. He was 26 years old and 40 pounds overweight. But the coach knew how much Jon loved to play. So whenever the team scrimmaged, Jon was allowed to join in.

"And I remember, one of the kids told me later on, he was, like, ‘I thought when you first put on your cleats, “What, this guy is going to be terrible — look at the size of him,” ’ " Jon remembers. "And he's, like, ‘Then you started playing, and you were good.’ He's like, ‘You got out of breath quick, but you were good.’ "

NCAA Eligibility

Players on the team started teasing Jon, telling him that he should join the team for real. But by then, he’d read the NCAA regulations. They’re available online in PDF files.

"And I would look at the PDF," Jon says. "And I'm, like, my eyes would get all squinty, and I would just stare at them and be like, ‘OK, it's saying … you can't do this.’ "

Jon kept staring at those PDF files, looking for some kind of loophole. He found one that would require him to attend graduate school at the same university where he finished undergrad.

But that wasn’t going to work. Jon had graduated UMass Boston with a 1.98 GPA.

"I wouldn't be able to get into graduate school anyways," he says.

So he approached the compliance officer at Southern Maine, where he was helping with the team, to see if that school would petition the NCAA for a medical exemption, just like schools often do for a player who’s suffered a season-ending injury.

"And he's, like, ‘Well, that's not a thing. That's not a real rule,’ " Jon says. "And I was, like, ‘Well, we should make it one.’ "

Jon Cross and Southern Maine filed the paperwork. Jon received a letter saying the request was denied. So did the compliance officer. But …

"He goes, ‘Yeah, but we got a phone call,’ " Jon remembers. "He says, ‘They said no, but they'd like for you to appeal it, because they think your story's kinda interesting.’ "

Jon gathered letters from doctors. And he wrote his own letter, explaining how much it would mean to him to finish a college soccer season. He wanted to walk on the field on Senior Day, take a picture with his parents and present his mom with flowers.

"I don't know why I was so attached to that day," Jon says. "But I was. I was just, like, ‘I really think it would mean something to my family and myself.’ "

But while he was waiting for an answer from the NCAA, Jon’s mother was diagnosed with late-stage lung and brain cancer.

Jon traveled back and forth between Maine and Massachusetts to help care for her. And he kept working on his soccer skills.

"And also running, like a drug addict Rocky, by myself," Jon says. "And I'm, like, ‘I don't know if I'm even playing. What am I doing? Why am I dribbling this ball around?’ "

Finally, Jon called the NCAA directly — which is definitely not encouraged in those PDF files.

"I said, ‘Listen — am I playing, or what?’ " Jon says. "She's like, ‘Who, who is this?’ I'm, like, ‘This is Jon Cross.’ And, she's like, ‘Oh.’ And she got all weird and, like, quiet.

"She's like, ‘We just got out of a meeting for you. You must have caught them on a good day. You'll be the first person to get eligibility for this. Congratulations. You're playing next year.’

"I remember, I took the phone away from my ear and I was like, ‘I am?’ "

We’ve asked the NCAA to confirm that Jon Cross was the first person to be granted a medical eligibility waiver due to past drug abuse. They haven’t responded.

But the eligibility office at Southern Maine has confirmed everything else.

Finding Peace

All season long, Jon’s mom, Noel, was too sick to attend his games. Until Senior Day.

"And I remember, I got up that day, it was freezing cold," Jon says. "My dad's, like, ‘Your mom's coming. She's coming. She has to be at the game, she said.’ And I said, ‘OK.’ "

Jon Cross walked out onto the soccer field at the University Southern Maine, carrying flowers for his mom. The P.A. announcer introduced him.

"And they listed to the three schools that I'd been to," Jon says. "And I was, like, ‘I wish they'd skipped over that.’ And they were like, ‘Jon's a leader,’ and they were saying all these things — and I was like, ‘Am I?’

"Like, I can't believe I'm here. Because I thought I'd either be dead or in jail. Never thought I was going to be doing this that day.

"I gave flowers to my mom, my dad. Took a nice little picture. They got their day. And I'm just glad that I got to be a participant in their day, as weird as that sounds."

"And then what happened with your mom?" I ask.

"So I went home. I sat down on my couch. My phone rang," Jon remembers. "It was my dad. He says, ‘There's compilations with your mom's cancer.’ "

Brain cancer is a strange thing. Sometimes it moves slowly. Sometimes quickly. In the hours since she’d left the game, Noel Cross had lost the ability to walk and speak.

"So the last time I ever saw my mom walk on her own was off that field — speaking fluently, like I remember her," Jon says.

Jon Cross left his soccer team again. But this time they knew exactly where he was — back home, spending time with his mom. And a few weeks later, when the team played an away game not too far from Jon’s hometown, his teammates insisted that he take the field.

He had finally finished a full season of college soccer.

"Like, we didn't win a lot," Jon says. "I didn't play spectacular. I was, like, ‘You just accomplished something you can be proud of. You were a good teammate this year. You were a good son.’ "

Noel Cross died a month later, on Nov. 25, 2015.

These days, Jon Cross speaks to athletes about his addiction and how he keeps himself balanced in sobriety. And he’s an assistant coach at St. Joe’s College in Maine, where the players know his story and he leads them in yoga and meditation once a week.

This article was originally published on January 18, 2019.

This segment aired on January 19, 2019.