Advertisement

NFL Great Sid Luckman's Dark Family Secret

Resume

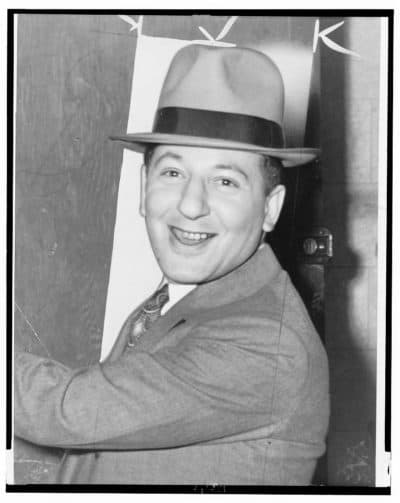

Writer R.D. Rosen remembers watching Chicago Bears games in the 1950s, alongside fans of an older generation. When the Bears struggled, they’d say, "Where’s Sid Luckman when we need him?"

Luckman led the Bears to four NFL championships between 1940 and 1946. He was one of the NFL’s biggest stars in the 1940s and early ‘50s. But recently, Rosen discovered Sid Luckman’s dark family secret.

"All I can say is, if this happened today, it would be all over media and social media and ESPN, and you couldn't get away from it," Rosen says. "And Sid would have to answer for it around the clock."

Brooklyn

The Luckman family story begins in Flatbush, Brooklyn about a century ago. It was a typical one. At first.

"Sid's parents were both immigrants from Russia," Rosen says. "Sid's mother was very well-educated. Sid's father was more of a shtarker. You know, he was a big, tough guy who started with a pushcart selling flour. And then he owned with his brother a big trucking company that trucked flour to the many, many little bakeries around New York City."

The Luckman family lived in a two-story brick house on Cortelyou Road. According to Rosen, Meyer Luckman was a good provider. Sid and his family never wanted for much. But Meyer was hardly an ideal father.

"Sid was given a bicycle, a precious bicycle, by Meyer," Rosen says. "And Meyer said, 'But if I ever catch you riding it in the street, I'm going to take it away from you.' Of course, he caught Sid riding around in Flatbush. He took the bike, and he chopped it up with an ax."

Sid Luckman excelled in sports. As he was becoming a high school football star, his father’s flour delivery business boomed. But, in the 1930s, Brooklyn was corrupt to the core. Businesses had to deal with the mob.

"Meyer Luckman became an associate of one of the two most powerful Jewish mobsters in Brooklyn: Louis Lepke," Rosen says. "Extremely powerful man.

"Meyer, I guess, proved himself to be a good businessman and trustworthy, and Lepke began to use him for other jobs, like delivering payoffs or collecting debts."

Meanwhile, Meyer, in his late 50s, served as bookkeeper and brains of the Luckman Brothers Trucking Company. His brother-in-law, Sam Drukman, was the guy who collected money from truckers after they made their deliveries of flour. "So he had his hands on a lot of money. And it was well known he had a gambling problem," Rosen says.

It was only a problem because Sam Drukman seldom won. His losses piled up. Meyer began to suspect his brother-in-law was embezzling from the business to pay his debts. Meyer confronted Sam, but that didn’t put an end to it.

"It reached the point where he could not take it anymore," Rosen says. "He wanted to eliminate this problem. Meyer just could not abide what his wife's punky little brother did to him."

March 3, 1935

"[Meyer Luckman] tells his brother-in-law to come to the warehouse to see about some business," Rosen says.

The company was headquartered at 225 Moore Street, a brick one-story warehouse in Brooklyn’s Bushwick neighborhood.

"At about 8:30, somebody calls into the cops, terrified. 'Something is going on at the Luckman Brothers Trucking Company. I hear screaming. Get somebody here immediately.' So cops show up. They break into this warehouse. And they find a still-warm corpse in the rumble seat of a Ford coupe," Rosen says.

It was the body of Sam Drukman. He’d been beaten with a sawed-off pool cue weighted with lead and tied up in a manner well-known to the Brooklyn mob and its victims.

"You tie their hands to their ankles behind them and then cinch the rope around their neck," Rosen says, "and every move you make, you strangle yourself."

A New York Times reporter showed up at the scene not long after the cops did. He’d later report:

When I when I got there, I slipped on the floor. I assumed it was motor oil. And it turned out to be blood.

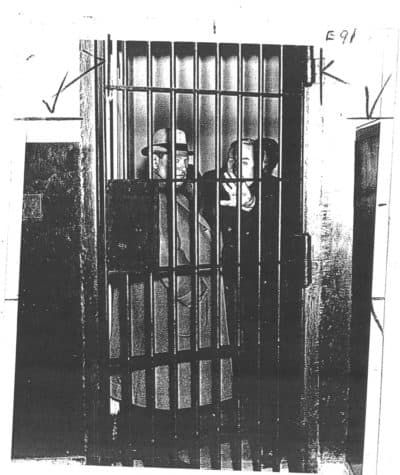

"Now the cops, they also hear some rustling, some whispering, and they find three men crouched behind a truck at the other end of the warehouse," Rosen says. "Two of the men are apprehended almost immediately."

They were Meyer’s nephew Harry Luckman and professional killer Fred Hull.

"The third one begins to run, and he's a portly older man," Rosen says. "He goes out a side door. A cop gives chase and fires a pistol shot over his head to stop the guy. That's Meyer Luckman, and he has blood on him."

The Trial

In April, the evidence went to a grand jury. But …

"By May of 1935 the grand jury has returned no indictment," Rosen says. "Because it's Brooklyn. Police officers were bribed, assistant D.A. was bribed. And members — we don't know how many — of the grand jury were bribed."

But Meyer wasn’t free for long. Brooklyn’s recently reelected district attorney was facing political pressure to crack down on the mob. The Sam Drukman murder case was presented before a new grand jury. On Nov. 14, 1935, Meyer Luckman was apprehended by two homicide detectives outside of his own house.

The murder trial of Meyer Luckman began on Jan. 18, 1936, during Sid Luckman’s freshman year at Columbia. It was standing room only in the courtroom.

"Sam Drukman’s father took the stand, pointed a finger at Meyer Luckman and said in Yiddish at the top of his voice, 'He killed my son! That man killed my son!' Sid's grandfather is accusing his father of killing his favorite uncle.

"Sid Luckman is watching this, and it's hard to believe he wasn't devastated," Rosen says.

Sid, along with his mother and three siblings, were present in the courtroom where his father and two accomplices were convicted of the murder of Sam Drukman. Meyer Luckman was sentenced to 20 years to life at Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

Sid's Rising Star

Amid the grisly murder trial headlines, Sid Luckman considered dropping out of Columbia. But head football coach Lou Little took his distraught quarterback under his wing and convinced him to stay. Sid quickly became a college football sensation.

"Now, in 1938, Meyer Luckman has been in Sing Sing for two years," Rosen says. "Sid appears on the cover of Life Magazine as America's best passer, because he's just upset Army with an incredible fourth quarter comeback at West Point. It's Life Magazine. It's a million readers. And the story describes him as the 'husky but shy son of a New York truck driver.' "

There was no direct mention of Meyer Luckman. And no mention at all of his crime.

"I mean, it's phenomenal that this story just disappeared," Rosen says. "That every sportswriter in town, who clearly knew what had gone on, knew about the murder, read the papers, knew about this guy Sid, did not ever mention Meyer Luckman in their coverage of Sid Luckman."

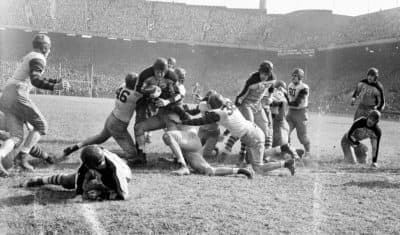

Luckman quarterbacked for three years at Columbia. The Bears selected him in the 1939 NFL draft.

"In his second season, he leads the Bears to the first of four championships, the most lopsided victory in NFL history," Rosen says.

The final score: Chicago 73, Washington 0.

"And he becomes a national sports celebrity."

Throughout it all, Sid always kept the family secret.

"Clearly, he didn't want this to get out," Rosen says. "And it became severed from the story of Sid Luckman, and then completely forgotten."

Sid visited his father in prison when he could. Little is known about those visits, because Sid never talked about them.

In early 1944, Meyer Luckman was suffering from a heart condition. He was eligible for parole in five years. Sid, who never believed his father was guilty, tried to get him out of Sing Sing on compassionate release.

"Didn't work," Rosen says.

Meyer Luckman died at Sing Sing in late January of 1944.

"And never saw his son play a single game in college at Columbia. Or for the Chicago Bears," Rosen says.

'Not Everybody Can Keep A Secret Like That'

In Sid Luckman’s 1949 ghostwritten autobiography, he barely mentions Meyer Luckman at all.

"The closest he comes to mentioning his father's name is the dedication. He says, 'To Dad Luckman, who played the hardest game of all.' That's it," Rosen says.

In 1996, during an on-camera interview for the Lincoln Academy of Illinois, Sid mentioned his father. But not the murder.

My dad was sick. He lost a lot of his money in the stock market. And he really never did recover.

To the very end, he can't talk about it," Rosen says. "Cannot talk about it."

Only one of Sid’s three children, his son, Bob, knew their grandfather had gone to jail for murder. But Bob didn’t know the victim had been his great uncle, Sam Drukman.

"Not everybody can keep a secret like that," Rosen says. "Not everybody can go through life bearing that burden alone."

Sid Luckman died in 1998. He was 81 years old.

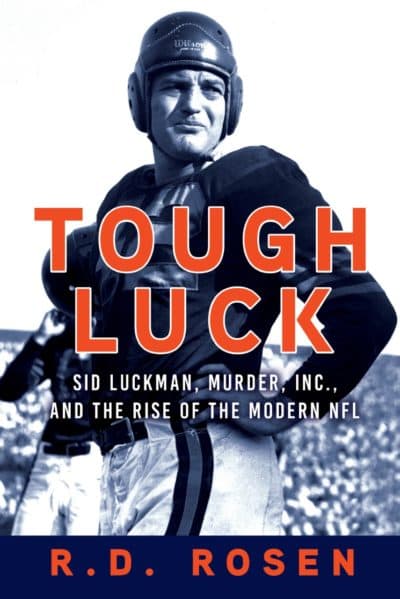

R.D. Rosen’s new book is “Tough Luck: Sid Luckman, Murder, Inc. and The Rise of the Modern N.F.L.”

This segment aired on November 23, 2019.