Advertisement

‘From Heroes To Villains’: CCNY Basketball’s Dramatic Fall From Glory

It’s around 1:30 in the morning on Feb. 18, 1951. Detectives from the New York District Attorney's office are standing on the platform at old Penn Station, waiting for the train from Philadelphia.

"It's a cold, drizzly night," author Matthew Goodman says. "It's kind of a scene out of a film noir with everybody bundled up in overcoats and fedoras."

The detectives are there to arrest three members of the City College of New York men’s basketball team.

A Team Playing At The Hub Of Sports Gambling

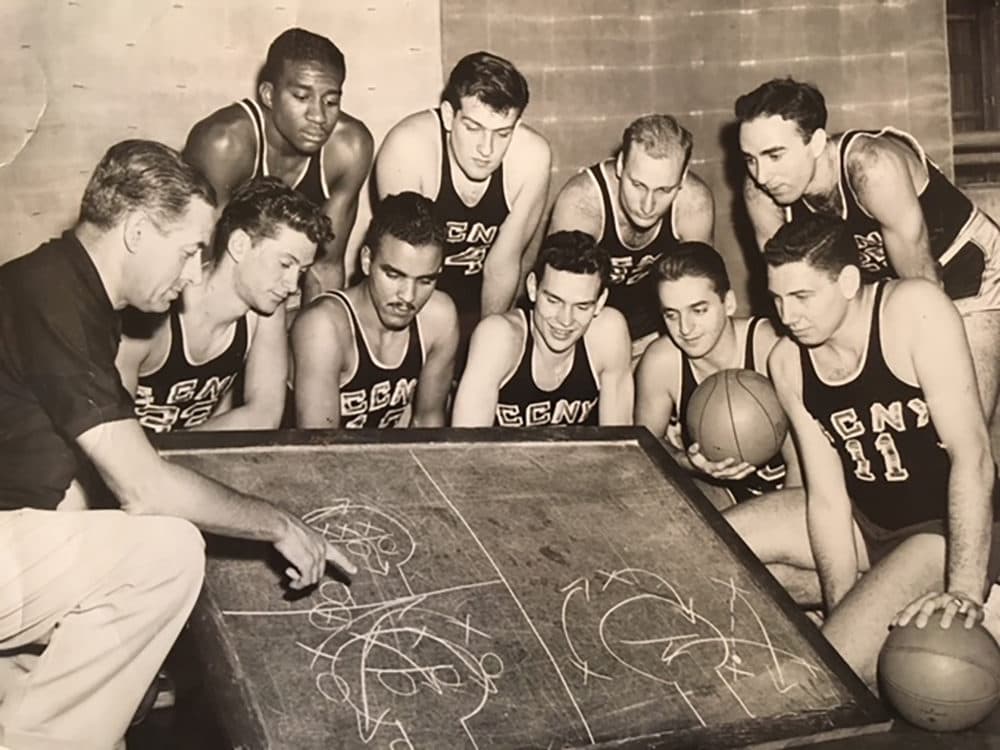

During the late 1940s, the City College of New York men's basketball team featured an all Jewish and African American roster. It was unusual for the time, but it made sense. This was New York City, the home of so many minorities.

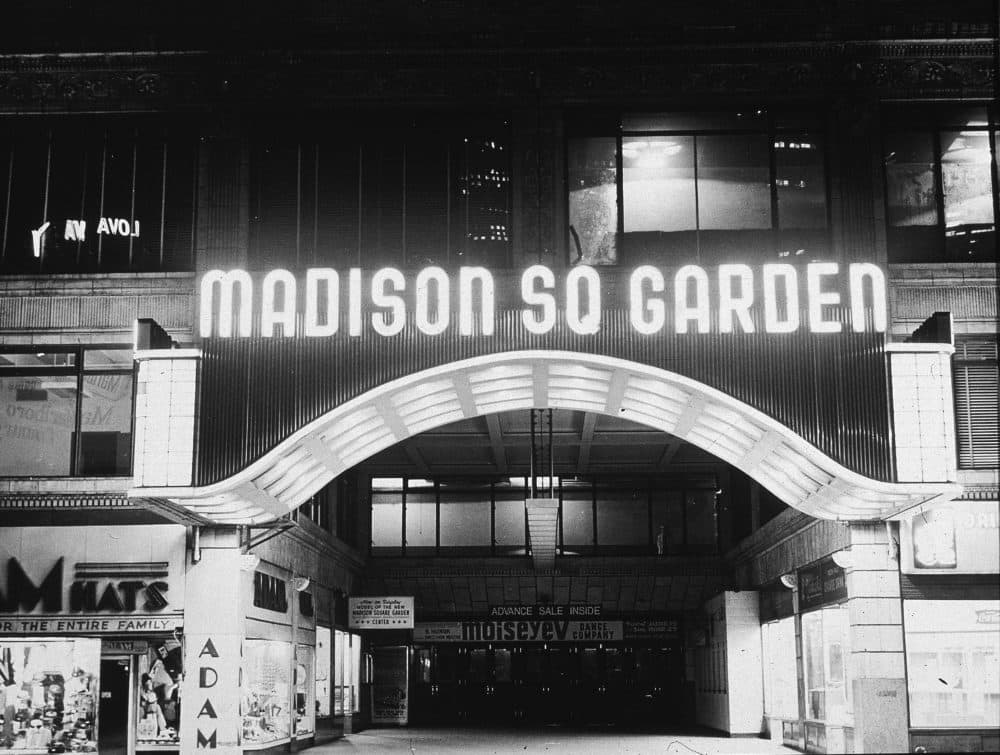

City College played almost all of its games at the world’s most famous arena, Madison Square Garden.

"City College would play, you know, a double header at the Garden, and they would invariably draw a full house, 18,000 screaming fans," Goodman says. "The New York Knicks had trouble drawing seven or eight thousand fans. And in fact, when there was a scheduling conflict, the Knicks got moved downtown to the dilapidated old 69th Regiment Armory on 23rd Street because the college game was by far the bigger game."

And there’s another reason it’s important to this story that City College played in Madison Square Garden.

"It's estimated that there were 4,000 bookmakers operating illegally in New York," Goodman says. "About $300,000 was bet on each game that was being held at the Garden. Much of it — as everybody knew — from inside the Garden itself."

At the center of that gambling scene was Harry Gross, a bookmaker from Brooklyn.

"His syndicate was taking in $20 million a year in sports bets, which seems like a lot — which is a lot — but especially when you consider that that's worth over $200 million a year in today's currency."

Gambling was illegal, but Gross ...

"He was protecting himself, his syndicate, from arrest by doling out $1 million a year in what he called 'ice' — bribes — to policemen and to politicians to keep them from busting his organization," Goodman says.

Advertisement

Dealings In The Borscht Belt

When there are gamblers, there are cheaters. Back in the 1940s, their method of choice was point shaving.

"So, if, for instance, the point spread was 11 points, you could win the game by 10 points or nine points or eight points and so forth," Goodman says. "So a player, who might recoil at the notion of intentionally losing a game, might think, 'Well, what's the difference whether we win by six points or nine points?' "

City College established itself as the best team in New York. And the players already had the gamblers’ attention.

"A lot of these players first came into contact with bookmakers and gamblers actually not in New York City, but upstate in the hotels of the Catskills — you know, the so-called 'Borscht Belt,' " Goodman says. "These players from New York and from elsewhere around the country would get hired by the hotels in the mountains, ostensibly to work as waiters or busboys or lifeguards, because by NCAA rules, the hotels were not allowed to pay them to play basketball.

"But, in point of fact, they were being hired because they were basketball players. Each hotel had a basketball team, and the competition got pretty intense. There was always a raffle at the end of these games, and whoever had the ticket that was closest to the final score of the two teams’ combined points would win a huge pot. And the gambler would say, ‘You know what? If you can arrange it so that my number is the final number, I will give you half the pot.’ And that was where these players first began to take money to control the points."

'No, We've Come Too Far'

During the 1949-50 season, a few City College players were taking money and shaving points. It wasn’t every game, and it certainly wasn’t everyone.

City College finished that year’s regular season with a 17-5 record, best among the New York City schools. As a result, they had earned a bid to the NIT — at the time the most prestigious postseason tournament.

"[The gamblers] offered double the amount of money, $2,000 per player, to shave points in the tournament ... and they all told him, 'No, we've come too far.' "

Matthew Goodman

"Well, no one gave them much of a chance," Goodman says. "One of the newspapers referred to them as the 'darkest of dark horses.' "

It didn’t help that their first opponents were the defending champions, the University of San Francisco.

Before the game, the gamblers approached City College senior forward Norm Major, "and offered double the amount of money, $2,000 per player, to shave points in the tournament," Goodman says. "He felt obligated to bring that offer to the other members of the starting five, and they all told him, 'No, we've come too far. We're gonna play clean in the tournament.' "

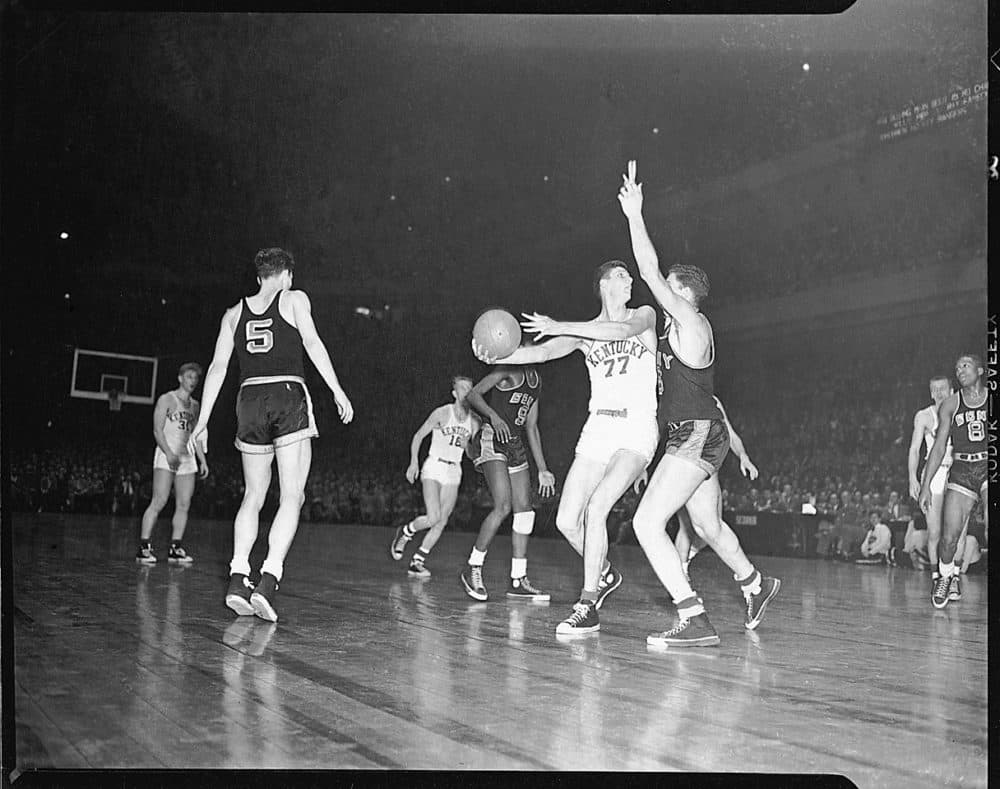

In the opening round against USF, City College pulled off an improbable upset with an overwhelming 65-46 victory. In the second round, the quarterfinals, City College was slated to play against the University of Kentucky.

Becoming National Heroes

"The University of Kentucky was to college basketball, much like what the New York Yankees were to Major League Baseball," Goodman says. "They were the overwhelming favorites. But this is the other thing about Kentucky: They had never had a black player on their team. And they were led by head coach Adolph Rupp.

"He had actually told a group of New York sportswriters a few years earlier that the Lord didn’t want 'a white boy to play against a colored boy,' as he put it. 'Else, he wouldn’t have painted them different colors.' And when they came to New York at City College, the game was seen as not just a basketball game, but almost as a kind of what we today would call a culture war.

"From the opening tip off, City just played an incredibly fast game, up and back, up and back, the ball moving fast like a pinball up a chute. The favored Kentucky Wildcats seemed old and slow, confused. The final score of the game was City College 89, Kentucky 50."

In the semifinals, the underdog City College beat Duquesne by double digits. Then they defeated Bradley University to win the 1950 NIT.

"And they instantly become heroes in New York City and for many fans, particularly Jewish and African American fans, around the country," Goodman says. "Nat Holman, the coach of the team, goes on The Ed Sullivan Show. The players are photographed in a full page photo in Life magazine.

"They seem to embody so much of what New York wanted to believe about itself: the notion of racial harmony, of civic virtue, the triumph of the outsider. New York's newspapers refer to them again and again as 'our boys' and 'our champs.' They were heroic in the eyes of many, many New Yorkers."

An Investigation To Find 'Mr. G'

Meanwhile in Brooklyn, a relatively new district attorney named Miles McDonald had quietly been putting together an investigation into police corruption and gambling.

"He knew that there was a lot of corruption among the police department: that police, particularly plainclothes officers, were taking money from bookmakers to protect their illegal gambling syndicates," Goodman says.

Goodman says McDonald knew he couldn’t trust regular policemen because many had already been corrupted. So he recruited 29 rookies who went undercover and pretended to be students at City College and several other schools throughout New York.

"Miles Mcdonald had heard stories about a kind of a legendary bookmaker that he knew only by the name 'Mr. G.' He didn't know who Mr. G was," Goodman says. "But slowly, little by little, starting with these rookie cops, he began to add links to the chain, arresting one guy and then another and then another. Until, eventually he got all the way to the top, and he found out the identity of Mr. G. It was Harry Gross."

'From Heroes To Villains'

Still, McDonald lacked proof of a connection between the bookmakers and the players. Then, in January of 1951, two former Manhattan College basketball players involved in the cheating approached Manhattan star Junius Kellogg.

"At first he told them that he would do it," Goodman says. "But then he went to his coach, and told them what had happened. The coach in turn went to the district attorney, and Junius Kellogg was set up with a wire. And that was really the beginning of the players being arrested for point shaving."

Soon, three City College players were implicated after authorities wiretapped the phone of another former college basketball player who was acting as a liaison between players and gamblers.

"And then we turn to the night of Feb. 17, 1951," Goodman says. "City College had just played a game against Temple. They were returning to New York by train. The train pulls into the old Penn Station in New York. The players are met on the platform by detectives. And they're taken downtown to the district attorney's office on Center Street for interrogation.

"They're interrogated in separate rooms for hours. The players are not allowed to call attorneys. They're not allowed even to call their parents. Finally, after hours of questioning, they break, and they confess to having shaved points in three games during that season. And, literally overnight, they've gone from heroes to villains."

Three City College players were arrested that evening, and four more later on. In total, 32 players from seven different schools confessed their involvement in the point shaving. Bookmaker Harry Gross pled guilty to 66 counts of gambling and bribery and was sentenced to eight years in prison.

In the following years, most schools involved, like Kentucky and Bradley, rebounded from the incident. City College was never stripped of its championships, but it was banned from Madison Square Garden and eventually dropped down to Division 3. And they never reached the same level of fame or success ever again.

Matthew Goodman’s Book is “The City Game: Triumph, Scandal and a Legendary Basketball Team.”

This segment aired on April 4, 2020.