Advertisement

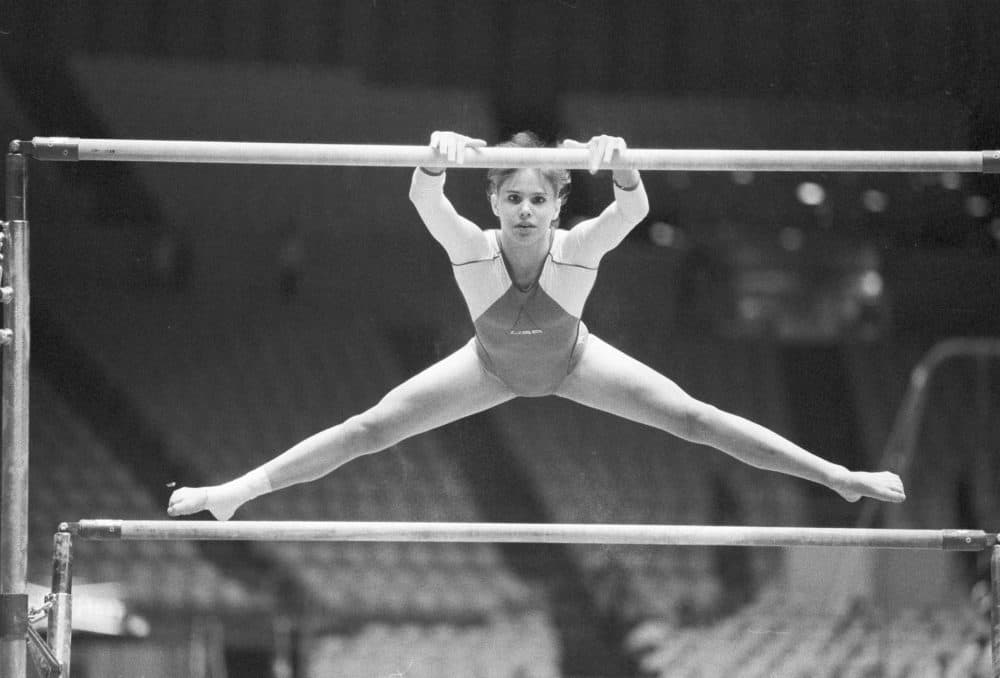

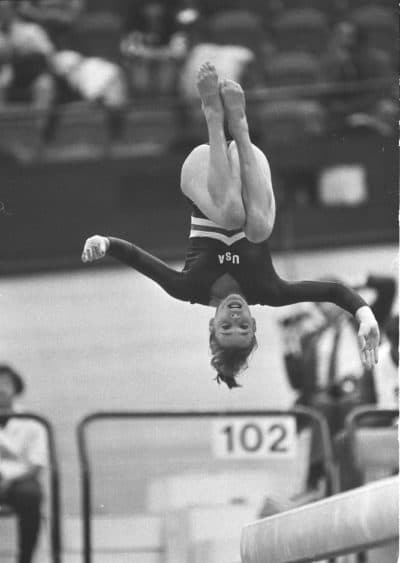

Former Gymnastics Champ Jennifer Sey Speaks Out Against Abuses In Her Sport

Resume

In 1976, "Happy Days" was the most popular show on television. "Silly Love Songs" by Paul McCartney and Wings topped the Billboard charts. And, that summer in Montreal, the world, including a 6-year-old Jennifer Sey, was introduced to Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci, the first ever to score a perfect 10 in the Olympics.

"And, you know, the fact that she was only 14 and she looked like a little girl, that was really — that had an impact, I think not just on me, but a lot of little girls across the country," Jennifer says.

At the time Jennifer was living in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, taking classes at Will-Moor Gymnastics. After seeing Nadia, she begged her parents to let her go as often as possible. Jennifer soon joined their team and competed on weekends.

"You know, back then, these were real competitions. Like, it wasn't like the 'everyone gets a trophy.' If you weren't good enough, there was no trophy. So it was pretty cutthroat," Jennifer says.

"And I just I loved everything about it. I loved how it felt. I loved being scared. I loved learning new things. I loved my teammates. And I just kept wanting to go more and more. And I just kept sort of doing better."

"At 9, I was demanding to go to another, better gym that had trained elite athletes."

Jennifer Sey

Jennifer went to the gym three or four times a week for three and four hour practices. After two years, she decided she wanted to compete for a shot at making the U.S. national team.

"And I said to my parents — I came home and I was like, 'I can't do that from this gym. I need to go to another gym,' " Jennifer recalls. "At 9, I was demanding to go to another, better gym that had trained elite athletes. And so we made the decision to go to another gym in New Jersey, a little further down the road."

Her stay-at-home mom drove her to and from practices.

"And I made my first national team at 10," Jennifer says.

This rigorous training was fun for Jennifer. She enjoyed the competition. And she loved her coach.

"She was an incredible human being. And I think she's everything a coach should be," Jennifer says. "You know, she would have considered herself — she's since passed away — an educator first and foremost, someone who sort of used sport to raise confident young girls.

"And, in fact, I remember a moment she asked me one summer —you know, we trained longer in the summer — and she said, 'Is there anything you want to do today?' And, in her mind, she was thinking of giving me the day off so I could go do something fun with my friends. And I was like, 'I wanna do an extra round of beam training, because I'm working on this skill.' And she thought that was so funny. But she was always encouraging us to be, sort of, whole people.

"But that wasn't what I wanted at the time. I wanted to be in the top six in the country. And so at 13, I had a very serious conversation with my parents, and we started to assess the different options."

There was this date looming ahead for Jennifer: her 15th birthday. Fifteen is the age gymnasts can move up and compete at senior events like the world championships and the Olympics. She knew she had to find a gym that could get her there.

After visiting three top gyms across the country, Jennifer decided on Allentown, Pennsylvania. From the moment she walked in, Jennifer noticed things at this gym were different.

"We were weighed twice a day. We were berated for what we ate and what we looked like," Jennifer recalls. "You know, I remember clearly, after a six hour practice, my mom brought me a bagel. And a coach snatched it from my hands like, 'You’re not gonna eat that, are you?' "

At first, Jennifer and her family drove the two hours back and forth everyday. Then, at 14, she moved out of her home to live with a coach in Allentown.

There, the insults and shaming continued.

"It was sort of control through fear tactics," Jennifer says. "And I was OK with it. I wasn't happy. And I quickly became, probably, depressed. But I, again — I was holding so fast to this idea that I could achieve this thing. And my whole worldview was kind of wrapped around that. And I thought, 'This is just the price that you pay.' "

Jennifer says she and the other gymnasts didn’t talk to each other about what they were experiencing.

"We sort of watch it on TV at the Olympics and think it's a team sport, but it's not," Jennifer says. "It's an individual sport. And you're vying for an individual spot. You're vying for your coach's favor and you're vying for the judge, you know. And I think we were just all too afraid to show any weakness."

Struggling to maintain her weight, Jennifer's injuries began piling up. Days before team trials for the 1985 world championships, she broke two fingers and got two black eyes after landing on her head on the balance beam. Jennifer was rushed to the emergency room.

"The doctor was told not to give me stitches, because that would make me not look right for the meet — because there's an aesthetic component," Jennifer says.

Despite those injuries, and while wearing layers of tape and makeup, she performed well. She was second in the country, qualifying her for the world championships. They took place just weeks later in Montreal.

There, Jennifer gave what she describes as solid performances in seven of the eight events.

"And it was my last event of the competition," Jennifer recalls. "It was bars. And I had a devastating fall."

"I knew it was really, really wrong, right?" she says. "Like, my foot was planted in the floor and my body spun around it, sort of spiraling around my knee. And I felt like I was screaming. I don’t know if that’s the case. People said I was silent, and it felt like it took forever for anyone to get to me."

Trainers rushed to Jennifer’s side. They quickly got her onto a stretcher and into an ambulance where her dad rode with her to the hospital.

"And I just remember being so — just desperate," Jennifer says. Like, this was it. 'This is over. I'm just starting to get to the level that I thought I could maybe get to, and now my career is done. And I don't know how to do anything else.' "

Jennifer underwent surgery. When she woke up, she learned that she had broken her right femur, an injury that is not as difficult to come back from as a knee or some other joint injury. Jennifer and her team were relieved by this news. Talk quickly turned to how to get her back in competition shape.

"I started with a traditional plaster. Then I went to something lighter," she says. "And then that doctor ... gave me something with a hinge so that I could kind of move it, so there’d be less atrophy. I was in the gym every day. I trained bars, which is crazy, with a spot. I just kept training. And I didn’t have the cast long enough. It was well under whatever the recommended time frame is — probably 12 to 15 weeks. I think I got it off in maybe eight or nine weeks.

For the next eight months, Jennifer just kept going, limping along, favoring her other leg, training for her next big competition: the 1986 U.S. nationals.

Jennifer won the all-around competition. But the years of struggles were finally catching up to her. The Olympics were two years away.

"I was sitting there thinking — you know, with my ankle in a bucket of ice — 'This is probably as good as it's going to get,' " Jennifer recalls. "And I remember it very distinctly. That was the real first time I ever was like, 'Maybe this is enough.' "

She remembers asking herself: Should I stop right now? But no adult, no coach, no parent posed that question to her.

"Well, who stops when they just won a national championship?" Jennifer says.

Jennifer deferred going to Stanford by a year to train for the ‘87 U.S. championships — only, her drive was no longer there. After the competition, Jennifer knew she was done. But her parents needed convincing.

"And I believe, to some extent, that they didn't understand the depths of my depression and didn't understand that it was physically and emotionally impossible for me to continue," Jennifer says. "I mean, I thought about killing myself. I — when I drove my car, I thought constantly about driving over the median into oncoming traffic. I didn't share this with them, so I don't think they understood it."

After a series of difficult conversations with her family, Jennifer left gymnastics.

When she got to Stanford in 1988, she was exhausted. Surrounded by smart, world-class athletes who were just hitting their prime, Jennifer felt like she was going into retirement — happy to sleep and eat, and to not have to rehab any injuries.

"I accepted treatment that I shouldn’t have accepted from friends and from romantic partners and from bosses. Like, I felt like that’s what I was worthy of."

Jennifer Sey

After Stanford, Jennifer started working for Levi Strauss. She rose through the company, ultimately becoming the CMO of global brands.

"But I was — I suffered," she says. "You know, I accepted treatment that I shouldn’t have accepted from friends and from romantic partners and from bosses. Like, I felt like that’s what I was worthy of. You know, I’d been treated that way for many years in the gym. And so I eventually went into therapy and came to understand a lot of this."

Jennifer decided to write her story.

"I sat down to write it not really thinking that I would ever get published, but just to sort of make peace and kind of understand it myself, I guess," she says. "And, I mean, at this point, I was already — I was nearly 40 and still sort of wrestling with it. But then I wrote it in almost like a fever state. I think in three months, or two months, I wrote a draft. And I sent it to a friend who was a novelist. And she said, 'It's a book. This is a book.' "

"Chalked Up: My Life in Elite Gymnastics" was published in 2008. Within months, Jennifer’s story — and the details of the horror she faced — was out there for the world to read. And the response from the gymnastics community was quick.

"It was harrowing and absolutely vicious and preyed on all my sort of biggest fears," Jennifer recalls. "And it's the tactic, the strategy, of the community, right? Like, 'There can't be any validity here. You are a loser. You were terrible. You are a failed ex-gymnast who never accomplished anything. And now you're just taking it out on this sport.' "

Jennifer heard it from gymnasts, coaches and gym owners.

"It was hard. It was really hurtful," Jennifer says. "And, despite being 40, despite being a mom, despite having nothing to do with the community, you — it is still your community. It's what I grew up in, you know?"

Readings in Pennsylvania, where she had spent years training, had to be canceled because of threats. The publisher feared people would be screaming and yelling at her.

But there was also another type of response.

"I got hundreds, if not thousands, of letters from people that said, 'Thank you. I felt this way, too. And now I feel less ashamed or less alone' or less whatever," Jennifer says.

Then in August of 2016, the Indianapolis Star published allegations of sexual abuse against U.S. gymnastics national team doctor Larry Nassar. Nassar eventually pleaded guilty to possession of child pornography and the sexual assault of minors.

As athletes and fans asked publicly how the crimes of Larry Nassar could have been allowed to go on for so long, Jennifer became, what she calls, a voice of history of the sport.

She went to D.C. and met with Sen. Dianne Feinstein on the Safe Sport Authorization Act. Passed in 2018, this law requires governing bodies and amateur sports organizations to report sexual abuse allegations to local or federal authorities.

While Jennifer is encouraged that allegations of sexual abuse are being believed and prosecuted, that they’ve led to resignations and firings, she still feels there is more work to done in the sport with regard to what she sees as other types of abuse.

"I don't believe, really, anything and certainly not enough — I don't believe — has changed. I mean, my coaches are still coaching, and they're incredibly abusive, and I don't think they've changed," Jennifer says. "If you are starving and you're told you're fat, if you're in pain and you're told you're lazy, you don't believe your own perception of the world. Imagine how disorienting that is for a child."

Jennifer's message for young women considering becoming part of the gymnastics community and U.S. gymnastics?

"Well, I think I would tell any young girl: 'Trust your own take on things. Don't accept poor treatment,' " Jennifer says. "I would tell their parents to pay attention and look out for them. I would say, 'Do it as long as it's fun. ... If you love it and you're having fun, then do it. If you're not, say something. Speak up. Stand up for yourself. Use your voice.' "

This segment aired on May 2, 2020.