Advertisement

Tales From Lou Gehrig's Long-Forgotten Newspaper Columns

Resume

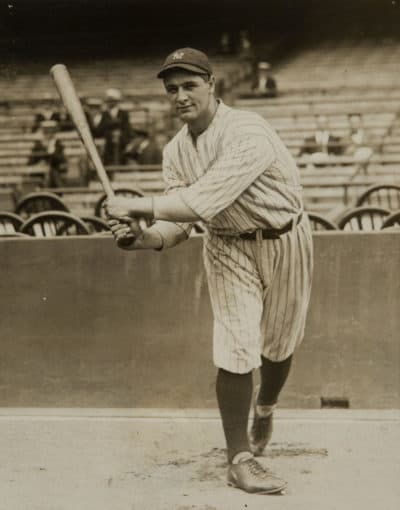

Former Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig is probably best remembered for one moment.

It was July 4, 1939, soon after the 36-year-old was diagnosed with ALS. On that day, 62,000 fans watched as Gehrig walked to home plate at Yankee Stadium, scratched his head, and said goodbye to the game of baseball.

He died less than two years later.

But a recent discovery gives fans the opportunity to remember Gehrig for more than just the sad end of his legendary career.

Lou Gehrig, Columnist

Two years ago, historian and writer Alan Gaff was researching World War I. He stumbled upon something unexpected.

"I was looking around in the Oakland papers and happened upon Lou Gehrig’s columns," Gaff says.

Gehrig, it turns out, wrote a series of newspaper columns that ran in Oakland, Ottawa and Pittsburgh during the New York Yankees’ 1927 season.

"And, when I read the first one, it's like, 'Wow, I don't remember ever seeing any reference to this before.' "

Gaff searched the internet for any mention of them by historians ... or anyone else.

"And there was nothing," Gaff says. "There's very few people alive now who would’ve even read them when they were in a newspaper. So historians have just kind of overlooked it. It's like, 'This is too good to be true. I don't ... you know, this just can't be happening.' "

Gaff learned that, in 1927, sports agent Christy Walsh arranged for his young client to join other baseball luminaries in writing a series of newspaper columns.

"So it was an opportunity for ball fans to learn something new about this new phenomenal kid who was only 24 in 1927. And he could explain how he rose to such prominence in his own words. It was a rags-to-riches story that Christy Walsh thought the country would love to hear," Gaff says.

Mother Gehrig

In one of his first columns, Gehrig wrote about his relationship with his mother, Christina, "who he refers to as his 'best pal,' " Gaff says. "There's only one mention of his father."

Heinrich Gehrig suffered from alcoholism and epilepsy, and he struggled to find work.

"But there are numerous mentions of his mother and the relationship that they had," Gaff says. "He was the only surviving child of four. So his mother doted on him his entire life."

And Lou doted on his mom in return.

In 1923, he was a student and baseball player at Columbia University.

"Gehrig had originally planned on finishing his college degree and going into some field of engineering because, at that time, he was essentially the sole support of his family," Gaff says.

In 1923, his mother was ill with pneumonia. In a column dated Aug. 22, 1927, Gehrig recalls how he changed his plan and decided to sign with the New York Yankees.

I’ll never forget the night I went home and told my mother that I was going to quit college and go into baseball. She broke down and cried when I told her. She insisted that I should stay on in school.

An engineering career seemed a safer long-term bet than pro ball did. But Gehrig wanted the immediate bonus that signing with the Yankees would provide.

"I’ll be well again soon," she said, "and then everything will be all right."

Like me, she didn’t think I could make good in baseball, and she was afraid that I would be let out in a few weeks, and then I’d be out of college as well as out of a job, too. It was a tough spot!

To the benefit of baseball, Gehrig signed with the Yankees for the annual salary of $2,400 and a bonus of $1,500, "which, by the way, is now worth less than $23,000 in today's money," Gaff says.

"But it was too good a deal to pass up," Gaff adds. "And his long term plan was to play baseball for a few years, save enough money to support his family until he got established in a lucrative career in private life."

'If You’re A Ballplayer, I’m the King of Siam'

At first, that decision must have seemed like a bad one. Gehrig played only sparingly during the 1923 and 1924 seasons. Gehrig began to hit in 1925. But the Yankees first baseman struggled defensively and on the base paths.

Gehrig didn’t hear the end of it from opponent Ty Cobb, the Detroit Tigers’ notoriously confrontational star player/manager. In one column, Gehrig wrote about the abuse Cobb directed at him as he struggled to establish himself.

"You think you’re a ballplayer," he said one day at the Stadium. "All you can do is hit that ball. If you’re a ballplayer, I’m the King of Siam." And he said it in a nasty tone of voice.

Once in 1925, when I was getting in the game only now and then, I went to [Yankees manager Miller] Huggins and asked him to get waivers on me and send me to the minors, where I could play regularly.

Cobb, then-Detroit’s manager, apparently heard about it. For the next time I saw him, he came over where I was.

"So you want to go to the minors do you?" he opened up. "Say, listen, rookie, you’ll never get away from me. I’ll claim you, and when I get you, I’ll send you to China, where it’ll take the rest of your life to get back."

Gaff says Gehrig didn’t hold that against Cobb.

"Because, months later, they would joke about it and get along as if they'd been fast friends for years."

In fact, as Gehrig wrote in one 1927 column:

Cobb is one of my best boosters today. When I finally got a job as a regular, he was one of the first men in the league to congratulate me. And many times he has gone out of his way to show me little tricks in hitting and in base running — tricks that only Cobb can show.

Financial Advice and Medical Attention From The Babe

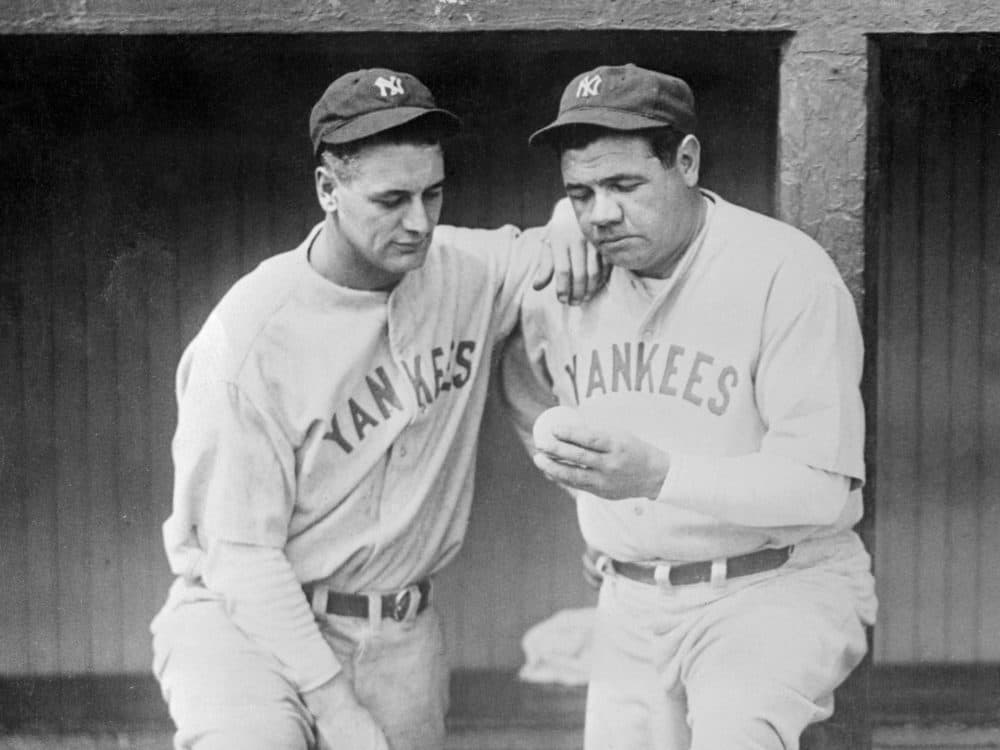

In his 1927 columns, Gehrig also told stories about the legendary Babe Ruth, who had been his mentor.

"At one point even offering Lou financial guidance in the dugout," Gaff says. "On one occasion, he was telling Lou, you know, 'I've made a fool of myself. I spent all my money. And you should plan for the future. Invest your money.' And, during this entire conversation, everybody on the Yankees team was just bent over double. Because, up to that point, Babe Ruth had squandered every cent he had ever made."

That season, Ruth and Gehrig were locked for a time in a tight battle for the home run title. Stories circulated about alleged acrimony between the two. But Gehrig publicly professed his admiration for the Babe. He shared the following story on Sep. 21, 1927.

Up at Toronto in an exhibition game a couple of years ago, the kids mobbed the field as the game ended. There must have been a thousand of them, and they all made a bee line for Babe. They struck him like a huge wave, and he went down flat on his face, literally buried under a landslide of kids.

It looked as though he must be trampled to death, and players and cops formed a flying wedge to rescue him. But before we got there, he emerged smiling, two or three youngsters clinging to his broad back, others hanging on his legs, and one under each arm. Most players would have been angered and disgusted. But the Babe was smiling as he trotted to the runway and still smiling when he disappeared under the stands.

As he started down in the dugout, he happened to look back. One little youngster was still standing over by first base, crying. Babe turned back through the mob again and went to the kid.

"What’s the matter, kid?" he asked.

"I got my hand stepped on," the little fellow whimpered. "It hurts."

"That’s all right," Babe replied, taking the lad in his arms. "We’ll get that fixed." And back he ploughed through the mob, the youngster held in his arms.

"Look out, here comes the ambulance!" he called. Then he took the lad into the clubhouse, and Babe bandaged the sore finger himself. After that, he gave the lad a baseball, a pat on the back, and sent him away smiling. That’s typical of the Babe.

'A Unique Insight Into One Of Baseball's Greatest Players'

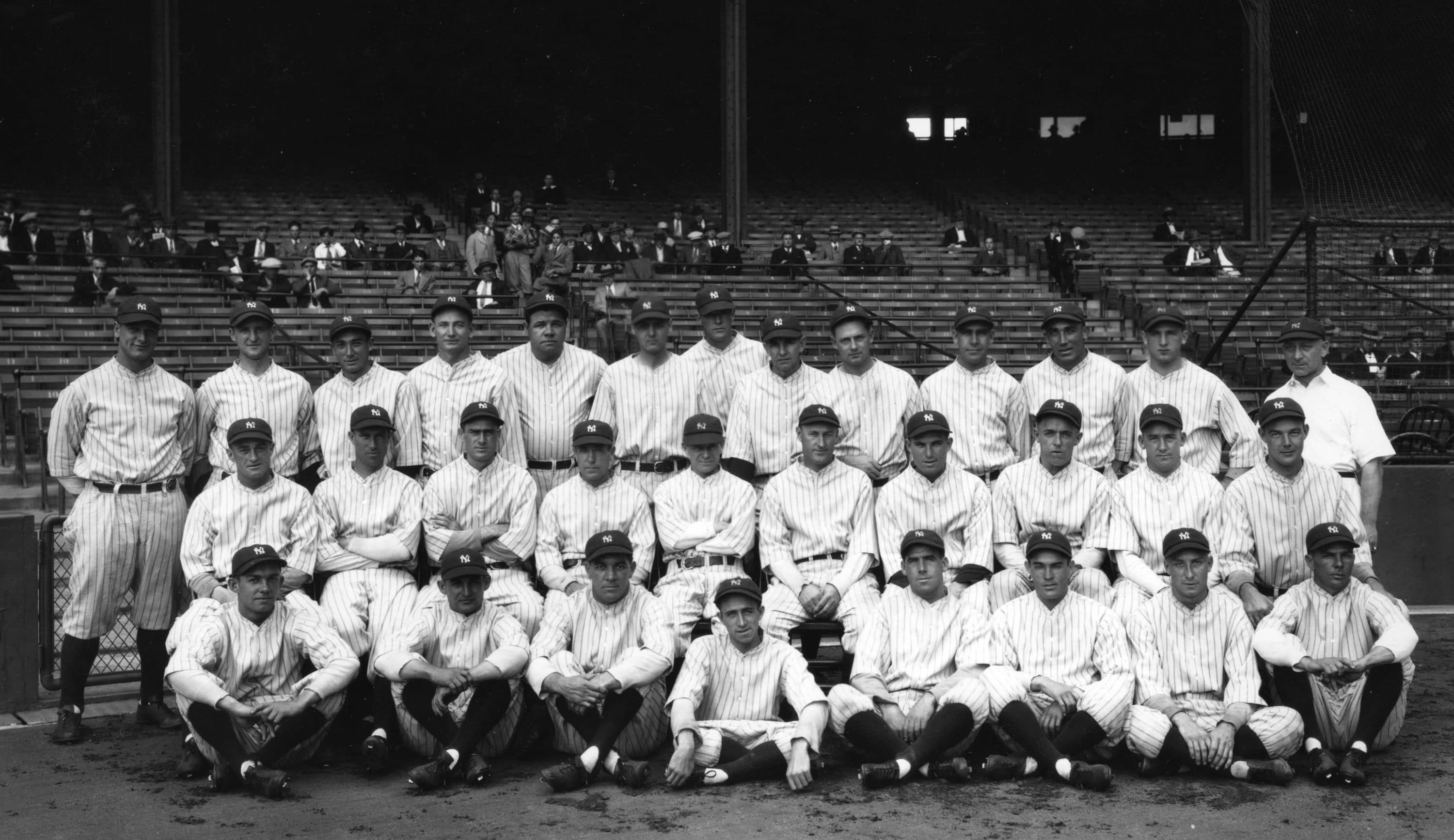

Gehrig was also friendly with Tris Speaker and Walter Johnson. In describing his relationship with contemporary greats, Gehrig always seemed awestruck. His humility often bordered on inferiority complex. Odd, for a guy with movie star looks and who batted cleanup on the team many consider to be the greatest ever.

In 1927, Gehrig led the league in Doubles, RBI, and Total Bases. The Yankees went 110-44, won the American League by 19 games, and swept Pittsburgh in the World Series. Gehrig was the MVP.

And yet, in his columns about that season ...

"He never thought of himself as more than just a cog in a team," Gaff says. "He was quite content to give credit to other people, when he deserved more than he was even getting in the press."

Some feel that Gehrig — like Babe Ruth and other ballplayers who wrote newspaper columns at the time — had a ghostwriter. But Alan Gaff disagrees.

"There are stories there that other people wouldn't have put in, you know, self-deprecating stories about himself."

After Alan Gaff stumbled upon Gehrig’s columns two years ago, he found a willing publisher right away. He presented Gehrig’s writing as chapters in a book, not as newspaper columns.

"But the words are all his," Gaff says.

And they flow as if the reader is sitting at the Gehrig family table, eating his mom’s German pancakes, listening to Lou speak candidly, telling stories long forgotten.

"It's a unique insight into one of baseball's greatest players," Gaff says.

After that 1927 season, Lou Gehrig never wrote another newspaper column. He played another 12 seasons, helping the Yankees win five more World Series and himself to one more MVP, in 1936. He set a consecutive games played record that stood for 56 years.

Just a handful of games into the 1939 season, the disease that would bear his name ended his baseball career.

Lou Gehrig died in 1941 at the age of 37.

'I Can Only Hope For The Best'

In one of Gehrig’s last columns from 1927, he looks back at the Yankees' championship season. And then, in what can now be described as a poignant foreshadowing, he looks ahead.

Of course, I am just a kid at the game, and I realize it. I still have much to learn, and I hope I still have many years in which to learn it.

As for the years that lie ahead, I can only hope for the best.

Alan Gaff’s book is "Lou Gehrig: The Lost Memoir." Gehrig’s excerpts were read by Brendan Connors.

This segment aired on July 11, 2020.