Advertisement

'I Absolutely Froze': The Night 'Spinner' Spencer's Dad Attacked The CBC

In recent years, athletes — including swimmer Michael Phelps, the NBA’s Kevin Love and soccer players Abby Wambach and Hope Solo — have spoken publicly about their mental health struggles. More and more pro sports teams and programs are making mental health a priority for their players. But 50 years ago, that was not the case.

Canadian Boy Makes Good

When you look up Fort St. James, British Columbia, the first thing you'll find is that it is a former fur trading outpost. It’s located about 600 miles north of Vancouver. It has a record low temperature of just over minus-50 degrees Fahrenheit. These days, there's not much going on there besides a bit of mining and logging. It’s a tough place to live.

Machinist and army veteran Roy Spencer raised his family in Fort St. James. He encouraged his son’s hockey career to help him escape.

So Dec. 12, 1970, began as a hopeful day for the Spencer family. 21-year-old Brian was in his second season with the Toronto Maple Leafs. He played left wing. His role was to instigate and to fight.

"Give them hell, son. We are mighty proud."

Roy Spencer telegram to his son, Brian

The Leafs' game that night was being carried on the country’s most popular television show.

For Roy Spencer, the prospect of watching his son on CBC’s "Hockey Night in Canada" was a dream come true. Brian told his father that he was going to be interviewed during one of the intermissions. Now all their hard work was paying off.

The normally introverted Roy Spencer invited friends and family to his Fort St. James home for a watch party. He bought a big TV antenna because CKPG, the closest CBC affiliate carrying "Hockey Night In Canada," was about 100 miles away in Prince George.

But, sometime before the game began, Roy Spencer learned that CKPG would be carrying a different game: the one between NHL newcomers — the Vancouver Canucks and the California Golden Seals.

'This Gentleman Has A Problem That He'd Like To Discuss With Us'

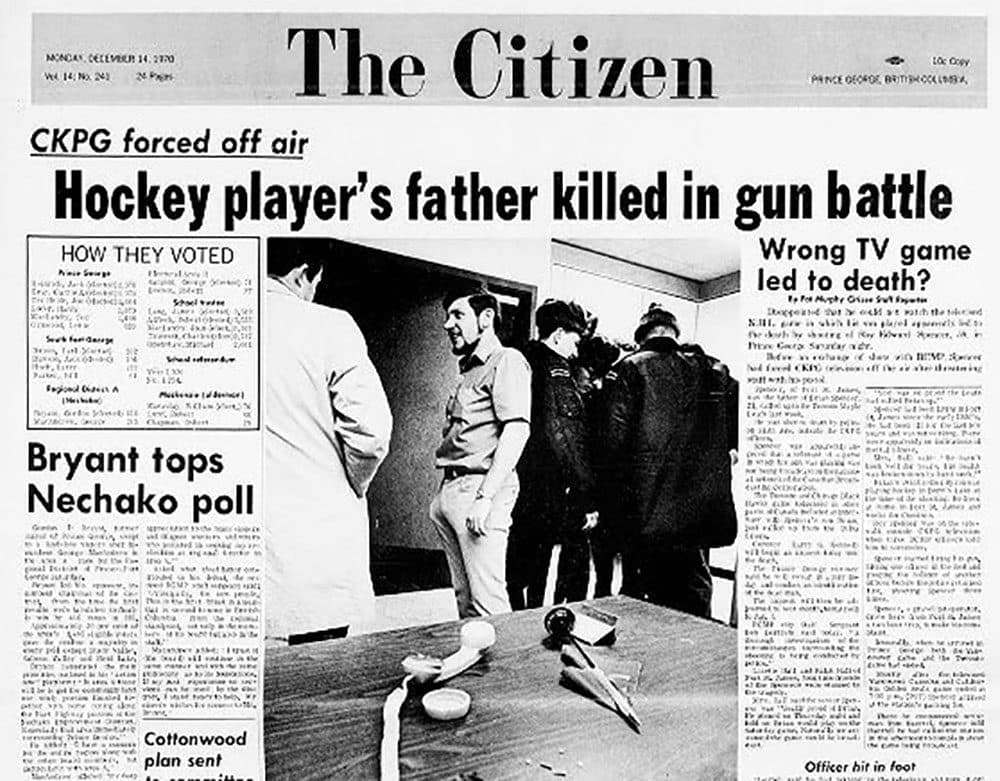

Reporter John Rea took a phone call in the CKPG news room.

"Maybe 5:30, something like that," Rea says. "He didn't identify himself but was very, very upset. He wanted to watch the Maple Leafs."

Around the same time, receptionist Carole Fawcett was settling in at the front desk for what she knew would be a busy evening. There was a local election in Prince George, and her soon-to-be fiancé, news director Stu Fawcett, had hired her as a temp. At about 7:30 ...

"I was looking for a key for the photocopier when, all of a sudden, Tom Haertel, one of the newsmen, came in through the front door that had been locked," Fawcett says. "And I noticed that right behind him was a very agitated-looking man. And he had a newspaper, and he was sort of holding it in front of him."

Haertel said something to Fawcett, and the two men continued down a hallway.

Moments later, Fawcett looked up again from her desk. The yet-unidentified man had returned and was standing in front of her, brandishing a 9mm pistol.

"And I absolutely froze," Fawcett says.

Advertisement

"And he lunged towards me and pulled all the wires out of the console of the phone. As he grabbed the phone from me, it hit me on the side of my face. And I flattened myself against the wall behind me, not knowing what he was going to do. I was petrified."

The assailant left the reception area and walked back down the hall toward the newsroom.

"And, at that point, I ran as fast as I could into the television studio and flung the studio doors open and wanted to tell them that there was a man at the front desk with a gun," Fawcett says. "And I just was going 'guh,' 'buh,' 'guh.' I just couldn't speak."

John Rea was in the newsroom when the intruder entered.

"And, with this gun in his hand, he sort of ordered us out of the newsroom, and he wanted to see the TV operation. We're led at gunpoint down the hall. There were, I guess, maybe four or five of us," Rae says.

"He said something about 'I've killed before. I don't want to kill anybody.' "

John Rea

CKPG also had a radio studio. There was a young man doing his very first shift as a DJ that night.

"And along the hall comes this crazy looking man with a gun waving all over the place," Fawcett says. "The poor kid locked the booth and flattened himself on the floor. And there he stayed for a good hour and a half."

With the pistol in the back of news director Stu Fawcett, the man herded the entire news staff into the television studio.

"And Stu was very calm and said, 'This gentleman has a problem that he'd like to discuss with us,' " Fawcett says.

The man lined everybody up against a wall.

"And this was when probably I was most afraid," Rea says, "because he had the gun pointed at us. I think he said something about 'I've killed before. I don't want to kill anybody.' "

"He said, 'I've killed before,' " Fawcett says. " 'And I have killed many times in the commandos. So turn off the television.' He said, 'There's going to be a revolution against the CBC.'

"He had driven down from Fort St. James that night, and he had ammunition and all sorts of stuff in his car to do some serious damage."

"And he was saying, 'Listen, I've got a problem with the CBC, and I want to watch the Toronto Maple Leafs game,' " Rea says.

That’s when Fawcett knew who was holding her and her colleagues hostage. She was not a big hockey fan, but she had heard of ‘Spinner’ Spencer.

"His son, Spinner, was going to be playing," Fawcett says.

John Rea and others tried to explain to Roy Spencer how network affiliates broadcast national programming.

"We only get one feed, and the feed we've got is the Canucks game," Rea says. "We didn't have a choice to pull up other programming, basically. You know, it's not up to us. We have no control. And then he said, 'Well, if I can't watch it, then nobody should watch hockey. Turn off the television station.'

"The operator at the control board was looking for approval. We told him to 'Turn it off, turn it off.' So he did."

"So anybody in Prince George at that time who was watching television, their screen would have gone black with no explanation," Fawcett says.

"And then, thank goodness, there was sort of a pause," Rea says. "And then he went out the front of the building."

'The RCMP Had Surrounded The Building'

The news staff felt they needed to cover the story unfolding in their own parking lot. So, ignoring the obvious danger, they followed Spencer outside.

"I was standing frozen in the studio," Fawcett says, "and the switcher was madly trying to get the television back on the air. And then I thought, 'I'm the only one in here.' "

So Fawcett followed the reporters into the snowy December night.

"The [Royal Canadian Mounted Police], unbeknownst to me, had surrounded the building."

Sometime after Roy Spencer had forced his way into CKPG, someone had managed to call the police.

"And, when they saw Mr. Spencer come out the front door, they said, 'Halt, police! Stop, or we'll shoot,' " Fawcett says.

"When they saw Mr. Spencer come out the front door, they said, 'Halt, police! Stop, or we'll shoot.' "

Carole Fawcett

"He crouched down, and he fired at the police standing by their cars in the parking lot," Rea says.

One of the officers was hit in the foot, another had his holster grazed.

"They fired back at him," Rea says. "And Mr. Spencer was shot and killed right in the front of the station."

According to one account, Roy Spencer died as Brian was being interviewed between periods at Maple Leaf Gardens.

Brian Spencer was back on the ice the very next day for a game against Buffalo. He tallied two assists and was praised in the press for his "mental toughness." Nothing I read about Brian Spencer mentioned anything about him receiving treatment or counseling of any kind.

Four days after that game, he delivered a eulogy at his father’s funeral. He said his dad was a kind, warm-hearted man. He said that Canada had let Roy Spencer down. And he read from the telegram his father had sent him before the Maple Leafs-Blackhawks game on Dec. 12, 1970:

Give them hell, son. We are mighty proud.

Carole Fawcett also returned to her job on Dec. 13, 1970.

"And I was working the front desk. And a gentleman, the poor man, came in as I had my back turned, and he said, 'Excuse me.' And I turned around. And, unfortunately for him, he was about the same build as Mr. Spencer," Fawcett says. "And I just screamed."

Fawcett was taken off the front desk and put to work in the record library. But she didn’t stay at CKPG for long. Every time she went in, she says, she got "triggered all over the place."

In 1970, there weren’t many resources for trauma victims, whether receptionists or pro athletes. Fawcett says she internalized hers for years. She didn’t realize how debilitating that could be until she trained to be a trauma counselor.

"I realized then how much it had indeed impacted on most of my life with that fear," Fawcett says. "Because I did live with fear, and I seemed to be easily put into the state of fear in a whole lot of settings."

Some say Roy Spencer’s behavior on the night of his death was attributable to kidney failure and uremic poisoning. Others say his military experience caused PTSD, and that alcoholism and mental illness ran in the family.

Spinner's Decline

After a 10-year career as an NHL left winger, Brian Spencer moved to Florida to work as a machinist. He lived in a partially-finished shack in a swamp, drank heavily, used drugs and associated with dealers and prostitutes. In 1987, he was charged with the murder of a Florida bartender. He faced a possible death penalty if convicted.

He was acquitted. But, just one year later, he was shot and killed during a robbery following a drug deal. He was 38 years old.

In 2013, the Toronto Maple Leafs formed a partnership with Canada’s largest mental health and addiction hospital. Half of the NHL’s 30 teams now participate in #HockeyTalks Nights, aimed at sharing mental health care information with players and fans alike. For current players, coaches and fans, that’s all good.

But those things came about four decades too late for Brian “Spinner” Spencer.

This segment aired on August 8, 2020.