Advertisement

What More White Sharks Mean For Cape Cod

Resume

With Jane Clayson

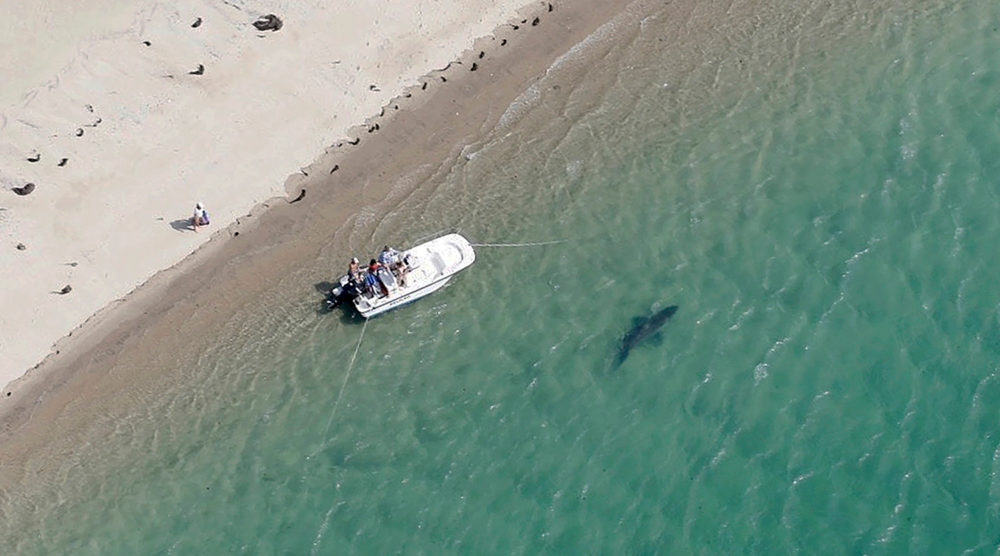

White sharks that hunt the coasts of Cape Cod attract tourists, key moments in scientific observation and seas of binoculars. We'll look at the science, fears and the economic impact of having these apex predators in our shores.

Guest

Doug Fraser is a Cape Cod Times reporter who covers the environment, fisheries and sharks. (@dougfrasercct).

From The Reading List:

Cape Cod Times: Sharks keep Cape towns, National Seashore on alert

"In the still morning air, gnats besieged those gathered for a 9 a.m. press conference Tuesday on the boardwalk at Marconi Beach. From the top of the bluff overlooking the beach, small glassy waves rolled in, and a touch of brown, free-floating seaweed made for a thick brown soup in a small band along the water’s edge.

"A couple of hours later, around noon, the first alert of the season was triggered with the sighting of a great white shark just 40 yards off the beach.

"The shark sighting seemed a fitting punctuation to the message that towns and officials with the Cape Cod National Seashore, a division of the National Park Service, were trying to make Tuesday morning.

"'It’s a wild ocean,' said National Seashore Superintendent Brian Carlstrom. 'That’s what it’s intended to be through the establishment of the Cape Cod National Seashore. Any time you go into the ocean you are taking a chance. We want to keep that as reasonable as possible, keep people informed about it, but you’re never going to be, nor will we ever be able to guarantee, 100 percent safety.' "

Cape Cod Times: Sharks and seals: A success story on Cape Cod

"Eighteen years ago, charter boat captain Joseph Fitzback and his customers held on tight as a 14-foot great white stripped a striped bass off a fishing line, then rocked the boat with a couple of exploratory bumps, 2 miles off Chatham’s Lighthouse Beach."

"Television crews and reporters lined up to interview Fitzback, but as the numbers of seals, and the sharks pursuing them, have increased, such interactions are almost commonplace. In a relatively short time the Cape has evolved from ocean playground to wilderness experience, and today Fitzback’s story might get little more than a few hits on social media."

"By now, the first of perhaps hundreds of great whites, the largest such aggregation on the East Coast, have returned to the Cape for the summer from their winter grounds to the south. They are hunting a gray seal population that has exploded from almost zero in the 1970s to nearly 30,000, possibly as many as 50,000, today, depending on the science you choose to believe."

"With five shark attacks on people since 2012 — including swimmers, kayakers, a paddleboarder and a fatal attack on a bodyboarder last year — surfers, swimmers, public safety officials and business owners now worry that the ocean is suddenly not safe. Some see an imbalance that requires corrective measures, like a cull of seals and maybe sharks to reduce risk and bolster fish harvests."

"But others marvel at a pair of conservation success stories in an era where species extinction is more often the news."

“'We need these species. They’ve been gone too long and their restoration should be celebrated,' said Joseph Roman, a conservation biologist and an associate professor and fellow at the Gund Institute at the University of Vermont."

"A gloomy United Nations report last month predicted that 1 million species are faced with extinction in the coming decades and that 66 percent of the ocean had been significantly altered by humans. A 2014 study by University of British Columbia researcher Villy Christensen showed that the global predatory fish population dropped by two-thirds over the past century, with the trend accelerating over the past 40 years. Many suggest that the government can, and has, played a big role in forestalling or even reversing those trends. NOAA’s 1997 ban on landing great whites, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, were largely successful in reversing the eradication of seals, whales and the great white."

Boston Globe Magazine: Sharks on Cape Cod: Just how scared should we be?

"It was one of those idyllic Saturday afternoons in summer, when the sun gently warms a cloudless sky, and the blue-green waters surrounding the Cape and Islands beckon so seductively that Bostonians forget all the traffic tie-ups they had to sit through to get there."

"A young man who had made the trip from Boston wasted no time hitting the waves with a family friend. The two men were out beyond the breakers when, suddenly, one of them looked over to see a giant eruption of water encircle the other. A great white shark had attacked the young man from underneath, leveraging the element of surprise in the classic style of the ocean’s apex predator. Snapping its jaw down on the young man’s left leg, the shark started to drag him below the surface of the water. The young man fought back, punching the shark in the face, which left him with more injuries: multiple lacerations to his hands and the loss of most of his left middle finger. Then, just as quickly, the shark let him go. The other man swam furiously toward the blood-reddened water. He used one arm to grasp his mangled friend and the other to paddle, all the while screaming for help."

"By the time they made it to land, the injured young man was in severe shock and had no radial pulse. Bystanders on the beach strapped him to a makeshift stretcher and then whisked him away."

"It was too late. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

A pall descended over Massachusetts. The next day the beaches were deserted, and up and down the coast people shook their heads and predicted that nothing would ever be the same."

"They were right — to a point. That incident took place 83 years ago, in Buzzards Bay. Claiming the life of a 16-year-old Dorchester kid by the name of Joseph Troy, the attack became a touchstone for coastal New England."

"The mental buffer served us well, even into this new century when shark sightings became more common. The gray seal population around Cape Cod was once hopelessly depleted thanks in part to the $5 bounties Massachusetts towns offered for killing the mammals so loathed by fishermen. In recent decades, the population has rebounded beyond conservationists’ wildest dreams. And the presence of tens of thousands of blubbery mammals has turned the Cape coastline into what shark researcher Greg Skomal calls “a gray seal café” for white sharks. As he puts it, 'They want to be where the meat is.'”

"The 'no fatality since 1936' buffer continued to offer comfort in recent years when the sightings turned into encounters: a middle-aged dad bitten on both legs when he was bodysurfing with his son in Truro in 2012; a pair of young women paddling off Manomet Point in Cape Cod Bay frantically calling 911 in 2014 after a shark bit into one of their kayaks. It even sufficed last August, when a neuroscientist from New York barely survived a gruesome attack by a great white in Truro."

Alex Schroeder produced this segment for broadcast.

This segment aired on July 11, 2019.